Article type: Commentary

16 May 2025

Volume 47 Issue 1

HISTORY

RECEIVED: 10 September 2024

REVISED: 3 April 2025

ACCEPTED: 24 April 2025

Article type: Commentary

16 May 2025

Volume 47 Issue 1

HISTORY

RECEIVED: 10 September 2024

REVISED: 3 April 2025

ACCEPTED: 24 April 2025

![]() The promise of justice reinvestment for First Nations children and young people in Australia

The promise of justice reinvestment for First Nations children and young people in Australia

Fiona Allison1 Associate Professor *

Affiliations

1 Jumbunna Institute for Indigenous Education and Research, University of Technology Sydney, Ultimo, NSW 2007, Australia

Correspondence

*Assoc Prof Fiona Allison

Contributions

Fiona Allison - Drafting of manuscript, Critical revision

Fiona Allison1 *

Affiliations

1 Jumbunna Institute for Indigenous Education and Research, University of Technology Sydney, Ultimo, NSW 2007, Australia

Correspondence

*Assoc Prof Fiona Allison

Part of Special Series: Children, Trauma and the Law Conference, October 2023![]()

CITATION: Allison, F. (2025). The promise of justice reinvestment for First Nations children and young people in Australia. Children Australia, 47(1), 3034. doi.org/10.61605/cha_3034

© 2025 Allison, F. This work is licensed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence

Introduction

This brief article introduces the concept of justice reinvestment as defined and applied in Australia by First Nations people, including as a mechanism with real potential to reduce over-representation of young First Nations people in the justice system. Examples are provided of how justice reinvestment is currently centring the perspectives and leadership of young First Nations people to address this issue, with discussion of how these might be further built upon as the justice reinvestment movement continues to grow across Australia. This approach is identified as important to realising the promise justice reinvestment holds to deliver better justice and other outcomes for First Nations peoples, with key barriers to achieving this identified as including a lack of readiness on the part of government for fundamental shifts in their responses to First Nations over-representation in the criminal justice system.

I am a non-Indigenous researcher who has worked on justice reinvestment from 2015 alongside First Nations communities around the country (including those referred to in this article) and at a more strategic policy-oriented level. This has been undertaken via a research role at Jumbunna Institute for Indigenous Research, University of Technology Sydney (UTS) and at Just Reinvest NSW, and through involvement with the Justice Reinvestment Network Australia. My work in this area aims to support First Nations-led implementation of, and advocacy for, justice reinvestment, with recognition that it is First Nations expertise, knowledge and leadership that needs to drive change through this approach. Note that this article uses different terminology to refer to First Nations peoples in Australia, including Aboriginal, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and Indigenous (only in describing a person who is non-Indigenous). The author recognises that this approach may not reflect the diversity of, and that there is not consensus amongst, First Nations peoples in Australia about how to be described.

Background to justice reinvestment in Australia

Justice reinvestment, or ‘JR’, is a framework that emerged in the early 2000s to tackle high rates of incarceration in the US. US-based JR was initially framed as a place-based and preventative approach that addresses causal factors for disproportionately high rates of (re-) imprisonment impacting particular neighbourhoods, cities or similar (Tucker & Cadora, 2003). Use of data has been a focus for JR from the outset; used, for instance, to identify places from which disproportionately large numbers of individuals cycle in and out of prison and reasons why this is occurring.

JR has always had an economic element too, arguing for a downstream shift in funding away from (ever-increasing) prison budgets into community-level resourcing that will respond to local drivers of incarceration. Diverting funding to a specific location to improve community-based drug and alcohol treatment or post-release reintegration services, for example, is identified as a better return on investment than continued expenditure on imprisonment. Prisons are seen as having little capacity to positively impact (and, in fact, exacerbate) social conditions contributing to higher rates of incarceration for certain communities (Tucker & Cadora, 2003).

Australia has its own issues with mass incarceration, particularly for our First Nations peoples, including First Nations children and young people. Our National Children’s Commissioner published a report on youth justice in 2024, making various recommendations for change to address this issue. The report identified that 57% of young people under youth justice supervision were First Nations, that First Nations young people were 23 times as likely as non-Indigenous young people to be under supervision and 28 times as likely as non-Indigenous young people to be in detention. First Nations people under youth justice supervision were also younger than non-Indigenous young people (6.1% aged 10–13, compared with 2.3% of non-Indigenous people under youth justice supervision) (National Children’s Commissioner, 2024)

First Nations young people are also more likely to return to youth detention (88% returning within 12 months from release compared with 79% of non-Indigenous young people), confirming that incarceration makes little positive difference to factors underpinning contact with the youth justice system. These ‘social determinants’ of contact with the youth justice system are broad ranging, encompassing early life experiences, systemic racism, unequal access to resources and the operation of the criminal legal system itself (see, for instance, McCausland & Baldry (2023)). Notably too, the National Children’s Commissioner also cited statistics pointing to the link between child protection and youth justice system contact. Children and young people in the child protection system are 12 times more likely than the general population to be under youth justice supervision (National Children’s Commissioner, 2024).

JR has been championed for some time by our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioners as a mechanism to address First Nations over-representation in Australia’s criminal justice system. It is important to note that JR’s various underpinnings are not new, in and of themselves. Rather, First Nations people have embraced JR because it aligns well with, and returns to, strategies implemented since colonisation (such as Nation (re-)building; e.g. Rigney et al., 2022) to resist the profoundly harmful impacts of the settler state, including those meted out by the criminal justice system.

JR wraps together, as a framework, approaches known to be effective for progressing First Nations-identified priorities and improving First Nations outcomes, including those centred on self-determination and culture, prevention and government accountability. This is illustrated by the following early comment on JR by the then-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, Mick Gooda:

Justice reinvestment provides a framework for what we have been trying to achieve in reducing Indigenous over-representation for some time. Imagine if the huge amount spent on Indigenous imprisonment could be spent in a way that prevents crime and increases community functioning, there was increased accountability and scrutiny about how tax payer funds on corrections are spent, communities were involved in identifying the causes and solutions to crime … Combine that with what we know about engaging Indigenous communities in partnerships and community development and we might just have a real life solution to the problem. (Social Justice Commissioner, 2009: pp. 41–42)

Others have also identified JR as a way forward for tackling over-representation, including the Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC). In their Pathways to Justice report into Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander incarceration, the ALRC recommended that governments fund First Nations-led JR initiatives and set up a national body to support and coordinate JR across jurisdictions (ALRC, 2017, Recommendations 4-1, 4-2). The Justice Reinvestment Network Australia (JRNA) has also been vocal in pushing for government support for JR, including with a focus on young people. JRNA is an Aboriginal-led collective of First Nations communities and others advocating for, and/or implementing, JR.

In 2022, the newly elected Albanese Government committed funding to JR, seeing its potential to contribute to achieving justice targets for reduced First Nations youth and adult over-representation within the National Agreement on Closing the Gap (Coalition of Peaks, 2020, Targets 10, 11). This investment consists of $81 million in funding over a 4-year period to establish a National Justice Reinvestment Unit (NJRU) and to resource up to 30 First Nations communities to implement JR through the National Justice Reinvestment Program (NJRP). Ongoing funding for JR after 2026 has also been committed to. The Justice Reinvestment in Central Australia Program provides an additional $10 million to JR initiatives in Central Australia in 2022–2026. There has been a significant amount of interest across Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities in accessing this national funding, with 27 initiatives funded as at January 2025.

Of note too, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities have been working with JR well in advance of the Federal Government’s investment, some of which have now been funded under the NJRU. The Maranguka initiative in Bourke, NSW, has led the way for JR in Australia (from 2012) followed by further initiatives in NSW and in WA, SA, NT and Qld (Allison & Cunneen, 2020). JR has been advanced in the ACT largely via government strategy (Justice and Community Safety Directorate, 2024).

Elements of justice reinvestment in Australia

In 2022, the Federal Government commissioned researchers at Jumbunna Institute for Indigenous Research, including the author, to undertake national consultations to inform design of the NJRU and NJRP (UTS ethics approval: ETH23-7953). In total, 44 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities were engaged in the design process, including those implementing JR or that were interested in or already working in ways aligned with JR. First Nations stakeholder organisations also participated (e.g. representatives from Aboriginal Land Councils, Community Justice Groups in Qld, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander legal services). Input was provided too from other non-government and some government stakeholders (e.g. philanthropic funding organisations, state/territory departments of justice or similar).

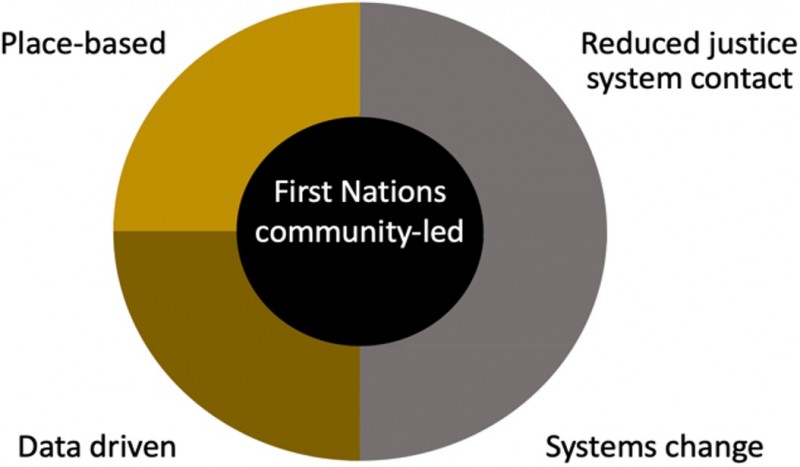

Through this process, five elements of JR were identified, based on both aspirational and existing approaches to JR implementation in Australia. The place-based, justice-focused and data-driven aspects of JR in the US were retained, with two new elements highlighted: First Nations community leadership; and systems change (see Fig. 1; Allison, 2023).

Figure 1. Five elements of justice reinvestment in Australia.

The First Nations leadership element of JR encapsulates the essential role of self-determination and culture to reducing over-representation in criminal justice systems and improving other First Nations outcomes (Lowitja Institute, 2021).

This leadership is necessarily reflected in all other JR elements. JR’s data element, for instance, aligns with Indigenous Data Sovereignty and Governance Principles in prioritising ‘community data’ over government and other administrative data to set a direction for each JR initiative (Lovett et al., 2022). Community data refers to data designed, collected and otherwise controlled by First Nations communities. JR’s place-based approach is identified as referring to nation groups as well as populations connected within Western-defined geographical boundaries (e.g. state/territory borders, Local Government Areas).

In these and other ways, JR is seen as a vehicle through which to transform relationships of power and to shift decision-making and resources away from the settler state back to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Whether this is ultimately achievable through JR will depend on government readiness to step up and respond to First Nations’ calls for change in these fundamental respects.

Related to this objective, and also important, are more specific reforms to government law and policy, a focus for JR initiatives both separately and collectively (e.g. JRNA, 2024). In a youth justice context, we have recently seen a number of state and territory governments reintroducing more punitive bail measures that will result in more young First Nations people being remanded, for instance. These need repeal. (See, for example, the complaint lodged on 2 April 2025 by Kurin Minang Researcher Hannah McGlade to the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination; McGlade, 2025).

Of course, given that interactions for First Nations children and young people across different government systems and services contribute to their over-representation in the justice system, including child protection as above, government reform is required beyond the justice area alone. Reforms likely to help address First Nations over-representation in both child protection and youth justice systems encompass prioritising investment in universal and targeted early intervention and prevention services, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander-led family support services, and increased implementation of the Aboriginal child placement principle, for example (SNAICC, 2024).

On a broad level, through both the systems change and First Nations-led elements of JR, First Nations communities seek to determine and lead their own solutions to incarceration, including via place-based Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander governance structures and processes. They are seeking equal partnerships that hold governments to account to actively support community-led solutions, including through the aforementioned reform to justice and other government systems that continue to cause so much harm to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. For these communities, JR has potential to address the highly complex set of drivers that feed First Nations over-representation, encompassing both social and political issues that exclude Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples from equitable participation in society and deny them sovereign rights, including to self-determination. As Devon Cuimara, co-chair of JRNA stated:

[JR] is a way of working that shifts power, resources and decision-making to First Nations communities to self-determine long-term responses that improve justice outcomes. These responses include culturally modelled community-governance models, sustainable economic initiatives, community-led research and evaluation, and community-led collaborative partnerships that uphold data sovereignty and protection of our old ways of working. (Quoted in Lowitja Institute, 2025: p. 38)

Children and young people in justice reinvestment

The remainder of this article considers how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are using JR to improve justice and other outcomes for children and young people. It draws primarily on specific examples from longer-standing JR initiatives and their implementation of the above JR elements and, to a lesser degree, from communities more recently stepping into JR through the NJRP.

To state the very obvious, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples want to see their children transition into happy, healthy adult lives with zero interaction with the justice system. This desire brings together those connected to place to advance a shared JR agenda for change directly centred on children and young people. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are also thinking strategically about how to have the greatest positive impact via JR on the much higher risk of contact with the justice system experienced in their communities. Understanding the importance of early intervention and prevention to reducing this risk, they identify a child and young person-centred approach to JR as making very good sense.

JR initiatives, firstly, may seek to implement interventions targeting those at higher risk of, or already interacting with, justice agencies; often prioritising younger people in this context (e.g. 10–18 years) to avert their entry into the youth justice system and ultimately the adult justice system. Examples of relevant activities include driver licensing programs that reduce driving-related offending for young people and increase their employment and other life opportunities, and community-run diversion programs offering culturally embedded supervision or mentoring on-Country for those on youth justice and other orders. Initiatives have also set up night patrols to connect with children and young people, including those who may fall into opportunistic offending while out and about with peers (Olabud Doogethu, 2019; Allison & Cunneen, 2020).

Of note, whilst the youth justice system in Australia might pull in those over the age of criminal responsibility, which varies across jurisdictions but may be as young as 10 years of age, JR initiatives might focus on children and young people of any age. Earlier intervention initiatives for this group have included school holiday programs and, in Moree, a Block Party and a Youth Forum for school-aged young people to talk about healthy relationships and increase connection to culture and access to support (Just Reinvest NSW, 2022). These types of activities respond, in part, to boredom and disconnection identified within JR initiatives as key drivers of child and youth contact with the justice system, as well as contributing to wellbeing of younger community members more broadly.

Interventions like the above are not, of course, specific to JR initiatives. What JR does differently, however, is to trial new, or adapt proven, interventions within a layered methodology or framework, including so as to enact the political and social transformation referred to above in discussion of key JR elements. For this reason, JR is commonly referred to not as a program but as a different way of working.

JR initiatives might, for example, set up a community-led intervention supporting Aboriginal students during their suspension from school, identifying these students (particularly those more frequently suspended) as at higher risk of justice system contact. These initiatives will simultaneously seek systems change at local and perhaps jurisdictional levels to ensure schools better comply with, and/or reform, school exclusion and related policy and law negatively impacting Aboriginal students.

Further illustrating the breadth of JR initiatives and the broad age ranges and issues they focus on, the Bourke Tribal Council leading and overseeing the Maranguka initiative has endorsed the Growing Up Our Kids Safe, Smart and Strong JR strategy for Bourke (Bourke Tribal Council, 2017). Reflective of a life-course approach to improving community outcomes, the strategy identifies three priority areas for change – ‘early childhood and parenting’, ‘children and young people 8 to 18 years of age’ and the ‘role of men’. Different activities fall under each of these priority areas and collectively progress a child and young person-centred agenda for JR in Bourke.

Demonstrating how JR brings together different components required to deliver change, initiatives may have an Aboriginal-led ‘backbone’ organisation working alongside a leadership group like the Bourke Tribal Council. The backbone holds together the various threads of activity within JR initiatives required to address the complex causes of over-representation. This team might consist, for instance, of a data role, engagement role, youth-lead role and coordinator role (see discussion of Mt Druitt’s JR initiative below). The team’s functions may include to build community understanding and engagement with JR or to engage service provider and other stakeholders with JR activities and leadership to ensure their contribution to delivering positive outcomes for the local community, including for its younger members.

One manifestation of this are the daily check-ins run by the backbone team at the Maranguka Hub in Bourke each morning, bringing services together (police, support services, etc.) to provide a more coordinated response to the needs of children and young people at higher risk of contact with the justice system and their families (KPMG, 2018). The transparency of the check-in process increases accountability of stakeholders to work together, avoiding silos and encouraging completion of actions committed to during these meetings. Addressing silos and increasing accountability of services is a common systems change priority progressed by JR initiatives. Other initiatives (e.g. in Katherine, NT) are establishing coordinated support for young people attending court with a similar intention.

In terms of JR and its strengthening of self-determination, Alister Ferguson has been at the forefront of JR in Australia and a community leader of JR in Bourke. He has referred to this and other work being done through Maranguka as an invitation to stakeholders to ‘align their resources and practices to our community led agenda’. Importantly, he identifies this agenda as part of a ‘nation-building process’, with the Bourke Tribal Council having brought together 24 different local tribes and families (quoted in Philanthropy Australia, 2022).

There is recognition, too, across JR initiatives that children and young people must be active participants in First Nations leadership, including to help drive systems change that matters to them. Mounty Yarns is a youth-led ‘creative advocacy and storytelling’ project connected with the Mt Druitt JR initiative in NSW. Through Mounty Yarns, young people draw on direct experiences of child protection and youth justice systems to speak to what is needed to change trajectories for their peers. Using this ‘community data’, they have created a resource that calls for establishment of a local youth-led youth service, responses to systemic racism and recognition of self-determination, amongst other things (Just Reinvest NSW, 2023). Some of these young people are also employed within Mt Druitt’s Aboriginal-led backbone in engagement, data and advocacy roles. A number of other JR initiatives are working with youth advisory or similar groups who will inform, and/or lead, local JR decision-making, with potential for this focus to be developed in further initiatives over time. This type of strengths-based approach both recognises the importance of, and builds on, existing local youth leadership. As youth leads for JR that have led the above Mounty Yarns work in Mt Druitt state:

We don’t want the next generation to go through what we went through. We want to be a voice so others don’t have to keep repeating stories. We need to make sure young fullas’ voices are being heard now. (Just Reinvest, 2023: p. 5)

Conclusions

As interest in JR grows across Australia, time will tell whether it continues to evolve in ways that firmly position children and young people front and centre. Without doubt, the voices of young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are absolutely crucial to ensuring the effectiveness of strategies like JR to tackle the entrenched issue of over-representation. Young First Nations people understand best how to ensure they lead happy healthy lives, absent of any justice system interaction. Moreover, these young people are seen as the future of First Nations communities and Nation groups looking to JR to create better futures for all First Nations peoples – one that is free of the ongoing harmful impacts of the justice system they continue to experience.

References

Allison, F. (2023). Design of the National Justice Reinvestment Program. Sydney: Jumbunna Institute for Indigenous Education and Research, UTS. ag.gov.au https://www.ag.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-01/national-justice-reinvestment-program-report-june-2023.PDF

Allison, F., & Cunneen, C. (2020). Justice reinvestment in Australia: A review of progress and key issues. Sydney: Jumbunna Institute for Indigenous Education and Research, University of Technology Sydney and Justice Reinvestment Network Australia. indigenousjustice.gov.au https://www.indigenousjustice.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/mp/files/resources/files/national-report-jr.pdf

Australian Law Reform Commission. (2017). Pathways to justice – An inquiry into the incarceration rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. Melbourne: ALRC. alrc.gov.au https://www.alrc.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/final_report_133_amended1.pdf

Bourke Tribal Council. (2017). Growing up our kids safe, smart and strong. Sydney: Collaboration for Impact. youtube.com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4kROj9R-m2w&feature=youtu.be

Coalition of Peaks. (2020). National Agreement on Closing the Gap. Canberra: Coalition of Peaks. coalitionofpeaks.org.au https://www.coalitionofpeaks.org.au/national-agreement-on-closing-the-gap

Justice and Community Safety Directorate. (2024). RR25by25 and Beyond: A justice reinvestment strategy for the ACT. Canberra: ACT Government. act.gov.au https://www.act.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/2563831/RR25by25-and-Beyond-A-Justice-Reinvestment-Strategy-for-the-ACT.pdf

Justice Reinvestment Network Australia. (2024, 17 October). Submission no. 186 to the Legal and Constitutional Affairs References Committee inquiry into Australia’s youth justice and incarceration system . Adelaide: Justice Reinvestment Network Australia. google.com https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://www.aph.gov.au/DocumentStore.ashx?id=0e22a197-60db-409e-bf1e-4fd76cc35dfd&subId=768429&ved=2ahUKEwiyubOekZ-NAxVh4zgGHah5KwwQFnoECBoQAQ&usg=AOvVaw1AXAVmaXhf18tUFVE7T_42

Just Reinvest NSW. (2022). Moree Youth Forum Report. Sydney: Just Reinvest NSW. justreinvest.org.au https://www.justreinvest.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Moree-Youth-Forum-Report-Mar-2022.pdf

Just Reinvest NSW. (2023). Mounty Yarns. Lived Experience of Aboriginal Young People in Mt Druitt. Sydney: Just Reinvest NSW. static1.squarespace.com https://static1.squarespace.com/static/644e27ff8602074e9b8ef945/t/64fe4341bf2ec6376e5d5db8/1694385003181/Mounty+Yarns.pdf

KPMG. (2018). Maranguka Justice Reinvestment Project: Impact assessment. Sydney: KPMG. indigenousjustice.gov.au https://www.indigenousjustice.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/mp/files/resources/files/maranguka-justice-reinvestment-project-kpmg-impact-assessment-final-report.pdf

Lovett, R., Prehn, J., Eckford-Williamson, B., Maher, B., Lee-Ah Mat, V., Bodkin-Andrews, G., & Walter, M. (2020). Knowledge and power: The tale of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander data. Australian Aboriginal Studies, 2020/2, 3–7. pc.gov.au https://www.pc.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/368024/sub073-closing-the-gap-review-attachment.pdf

Lowitja Institute. (2021). Culture is Key: Towards cultural determinants-driven health policy. Melbourne: Lowitja Institute. lowitja.org.au https://www.lowitja.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Lowitja_CultDetReport_210421_D14_WEB.pdf

Lowitja Institute. (2025). Close the Gap. Agency, leadership, reform: Ensuring the survival, dignity and wellbeing of First Nations Peoples. Melbourne: Lowitja Institute. lowitja.org.au https://www.lowitja.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Close-the-Gap-Report-2025_March.pdf

McCausland, R., & Baldry, E. (2023). Who does Australia lock up? The social determinants of justice. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy, 12(3), 37–53. DOI https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.2504

McGlade, H. (2025). Complaint lodged to the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. static1.squarespace.com https://static1.squarespace.com/static/580025f66b8f5b2dabbe4291/t/67ea290c1c3aff78641d7e91/1743399185829/United+Nations+CERD+complaint_youth+justice+in+Australia.pdf

National Children’s Commissioner. (2024). ‘Help way earlier!’: How Australian can transform child justice to improve safety and wellbeing. Sydney: Australian Human Rights Commission. humanrights.gov.au https://humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/document/publication/1807_help_way_earlier_-_accessible_0.pdf

Olabud Doogethu. (2019). Smart justice in the heart of the Kimberley. Halls Creek: Olabud Doogethu. olabuddoogethu.org.au https://olabuddoogethu.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/prospectus-booklet-olabud_WEB.pdf

Philanthropy Australia. (2022). The Maranguka Way – Cultural authority and respectful partnership. philanthropy.org.au https://www.philanthropy.org.au/news-and-stories/the-maranguka-way-cultural-authority-and-respectful-partnership/

Rigney, D., Rose, D., Vivian, A., Jorgensen, M., Hemming, S., & Berg, S. (2022). Gunditjmara and Ngarrindjeri: Case studies of Indigenous self-government. In P. Cane, L. Ford & M. McMillan (Eds). The Cambridge legal history of Australia. Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

SNAICC. (2024). Family Matters Report 2024. Family Matters: Strong communities, strong culture, stronger children. Melbourne: SNAICC. snaicc.org.au https://www.snaicc.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/250207-Family-Matters-Report-2024.pdf

Social Justice Commissioner. (2009). 2009 Social Justice Report. Sydney: Australian Human Rights Commission. humanrights.gov.au https://humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/content/social_justice/sj_report/sjreport09/pdf/sjr_2009_web.pdf

Tucker, S. B., & Cadora, E. (2003). Justice reinvestment. Ideas for an Open Society, 3(3). opensocietyfoundations.org https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/publications/ideas-open-society-justice-reinvestment