Article type: Report

14 April 2025

Volume 47 Issue 1

HISTORY

RECEIVED: 8 October 2024

REVISED: 19 December 2025

ACCEPTED: 4 April 2025

Article type: Report

14 April 2025

Volume 47 Issue 1

HISTORY

RECEIVED: 8 October 2024

REVISED: 19 December 2025

ACCEPTED: 4 April 2025

![]() Barriers to mental-health support and services for children and young people in out-of-home care: The Children in Care Collective’s audit findings

Barriers to mental-health support and services for children and young people in out-of-home care: The Children in Care Collective’s audit findings

Affiliations

1 Children in Care Collective, Australia

2 Institute of Child Protection Studies, Australian Catholic University, Melbourne, Vic., Australia

Correspondence

*Dr Lindy Annakin

Contributions

Lindy Annakin - Study conception and design, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting of manuscript, Critical revision

Lottie G. Harris - Study conception and design, Analysis and interpretation of data, Critical revision

Daryl J. Higgins - Study conception and design, Critical revision

Lindy Annakin1 *

Lottie G. Harris2

Daryl J. Higgins1,2

Affiliations

1 Children in Care Collective, Australia

2 Institute of Child Protection Studies, Australian Catholic University, Melbourne, Vic., Australia

Correspondence

*Dr Lindy Annakin

CITATION: Annakin, L., Harris, L. G., & Higgins, D. J. (2025). Barriers to mental-health support and services for children and young people in out-of-home care: The Children in Care Collective’s audit findings. Children Australia, 47(1), 3040. doi.org/10.61605/cha_3040

© 2025 Annakin, L., Harris, L. G., & Higgins, D. J. This work is licensed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence

Abstract

This article reports on the barriers experienced by out-of-home care (OOHC) service providers to finding timely and appropriate mental-health supports and services for the children and young people in their care. All children in care will have experienced trauma in some form. The mental-health challenges and poor outcomes for children and young people in OOHC, including the risk of self-harm and suicidal ideation, are well documented. Utilising the experience and practice wisdom of OOHC service providers, we identified common barriers to the provision of services to this vulnerable cohort. The most significant barrier, given its implications, was the lack of understanding of complex trauma resulting in the diagnoses of children that do not account for their trauma history and the misunderstanding of trauma symptoms as behavioural rather than mental-health concerns. The scarcity of mental-health services is a clear barrier to accessing timely and appropriate services, as is health professionals’ lack of understanding of the structures, processes and legal requirements of OOHC systems. The Children in Care Collective suggests three actions that would contribute to better services without waiting for the outcome of complex negotiations over increased health funding and resources: priority access to mental-health services for children and young people in OOHC; a focus on prevention and early intervention; and development of shared understanding between OOHC service providers and healthcare providers.

Keywords:

child abuse, child maltreatment, children’s rights, mental health, out-of-home care.

Background

The Children in Care Collective (the Collective) is an interagency think-tank with a national footprint formed in 2016. The Collective uses evidence-based practice, practitioner knowledge, academic research and the expertise of children and young people themselves to address difficult systemic issues for children and young people living in out-of-home care (OOHC) in Australia.

Members of the Collective are OOHC service providers, academic centres and academic experts in the areas of child abuse and neglect, child protection, OOHC, children’s rights and best interests. Together they provide a unique combination of practitioner and academic wisdom and experience.

One of the Collective’s priorities is improving the health, mental health and wellbeing of children and young people in OOHC. Its premise is that access to appropriate and sufficient mental-health support and healing is a right.

Issue

The poor mental-health outcomes of children and young people in OOHC is well established (Green et al., 2020; Leckning et al., 2021). Children who have experienced the child protection and OOHC systems are listed in the National Children’s Mental Health and Wellbeing Strategy as one of the cohorts of children known to be at increased risk of experiencing mental ill health (National Mental Health Commission, 2021).

The relative disadvantage experienced by this cohort of children and young people results from several interrelated factors including a history of abuse and/or neglect, ongoing poor physical and mental health, risk of self-harm and suicide-related behaviours, substance misuse, and the challenges their parent(s) faced, such as mental ill-health, homelessness, poverty, unemployment and violence (see for example: Mendes et al., 2011; Osborn & Bromfield, 2007; Russell et al., 2021).

Even when children and young people entering care have not experienced abuse or neglect, they will have experienced trauma in some form. Children may be placed in OOHC when parents are incapable of providing adequate care, when alternative accommodation is needed during times of conflict, or when parents or carers need respite (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2021). Being in care can, of itself, also be traumatising (Herrman et al., 2016).

The health system is struggling to provide for children and young people with mental-health needs (Devlin et al., 2022; McLean et al., 2021). There is a clear need for increased mental-health-service resources and funding. Beyond this, it seems that the mental-health needs of children in care are overlooked, misunderstood, misdiagnosed or viewed as too complex by health service practitioners (Bunger et al., 2021).

The experience and practice of Collective member agencies confirmed the reality of the issues identified in the literature as set out above. In addition, they identified bureaucratic barriers within OOHC systems that require complex navigation to obtain approvals, funds and even services. The structures and requirements of the OOHC system are also frequently misunderstood by mental-health-service providers.

Aim

To support its advocacy for improved access to services, the Collective sought to develop a practitioner-informed overview of the critical barriers experienced by OOHC service providers in connecting children and young people in care with timely and appropriate mental-health supports and services.

The purpose of audits conducted by the Collective was to systematically identify common barriers to the provision of appropriate mental-health services and supports for children in their care that are experienced by Collective member agencies and OOHC service providers more broadly.

Methods

Participants

All the participants in this project were professionals actively working for a range of OOHC service providers operating in New South Wales.

Initially, the Collective audited its own member agencies that provide OOHC services, requesting information about their challenges in accessing mental-health services and support for children and young people in their care, including those with acute suicidal or self-harming behaviour.

Some of these OOHC service providers operate services across Australia but all were reporting on challenges in New South Wales. Nine of the 11 (82%) service providers who were members of the Collective at the time responded.

To supplement the information gathered from its members, the Collective conducted a broader audit of OOHC service providers in a regional area of New South Wales. The area we chose includes metropolitan and regional areas as well as large and small rural towns because we wanted to know about services in a similar range of locations covered in the audit of Collective agencies. The agencies were approached via the NSW Department of Communities and Justice District Permanency Support Program Implementation Group of which they were members. A representative of the Collective attended a meeting of the Implementation Group to explain the project and its aims and to invite their participation. The response was very positive and agencies agreed to nominate a representative to complete the audit.

Eleven of a possible 17 respondents (65%) in the area completed the audit tool in 2023, with more than half of these being agencies who were not Collective members.

Both audits included a request for names and organisational details to avoid duplication but assured participants that their anonymity and the confidentiality of data would be protected in any reports.

Audit tools

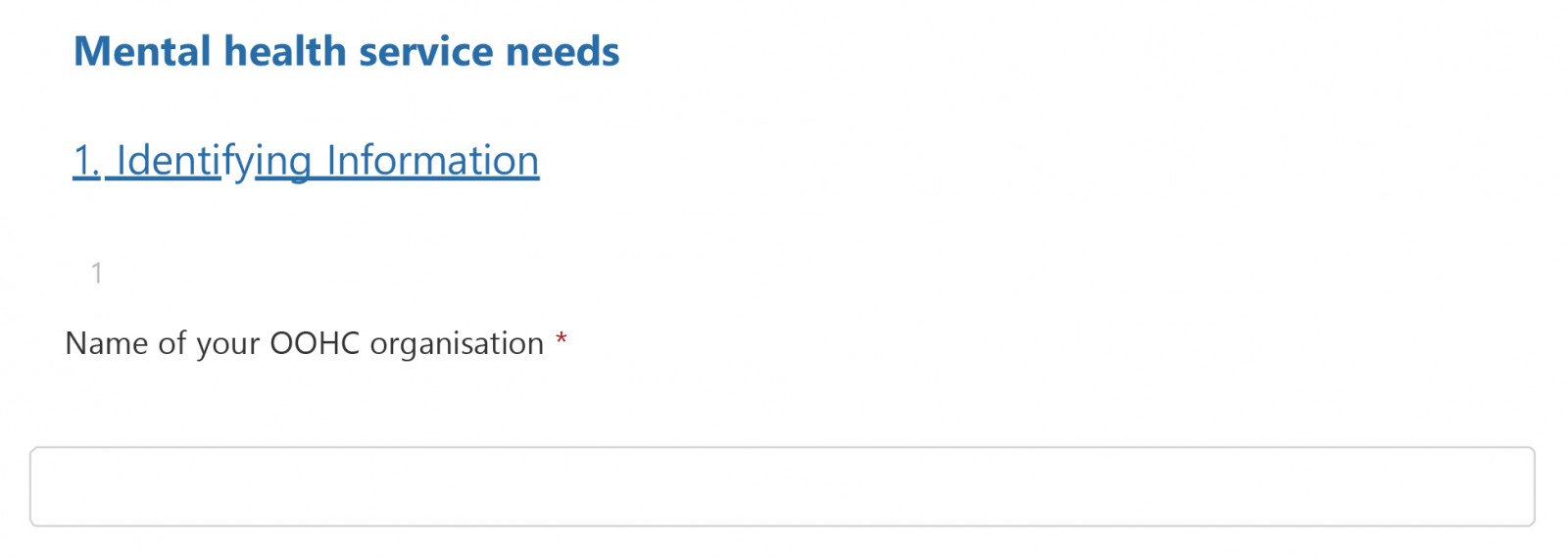

Audit 1

The research question was initially identified through discussions within the Collective about the difficulties OOHC service providers face in accessing appropriate and timely mental-health support for the children and young people in their care. In 2022, a small working group of Collective members developed questions that would enable the systematic collection of information about these challenges (see Appendix 1 for Audit 1 questions).

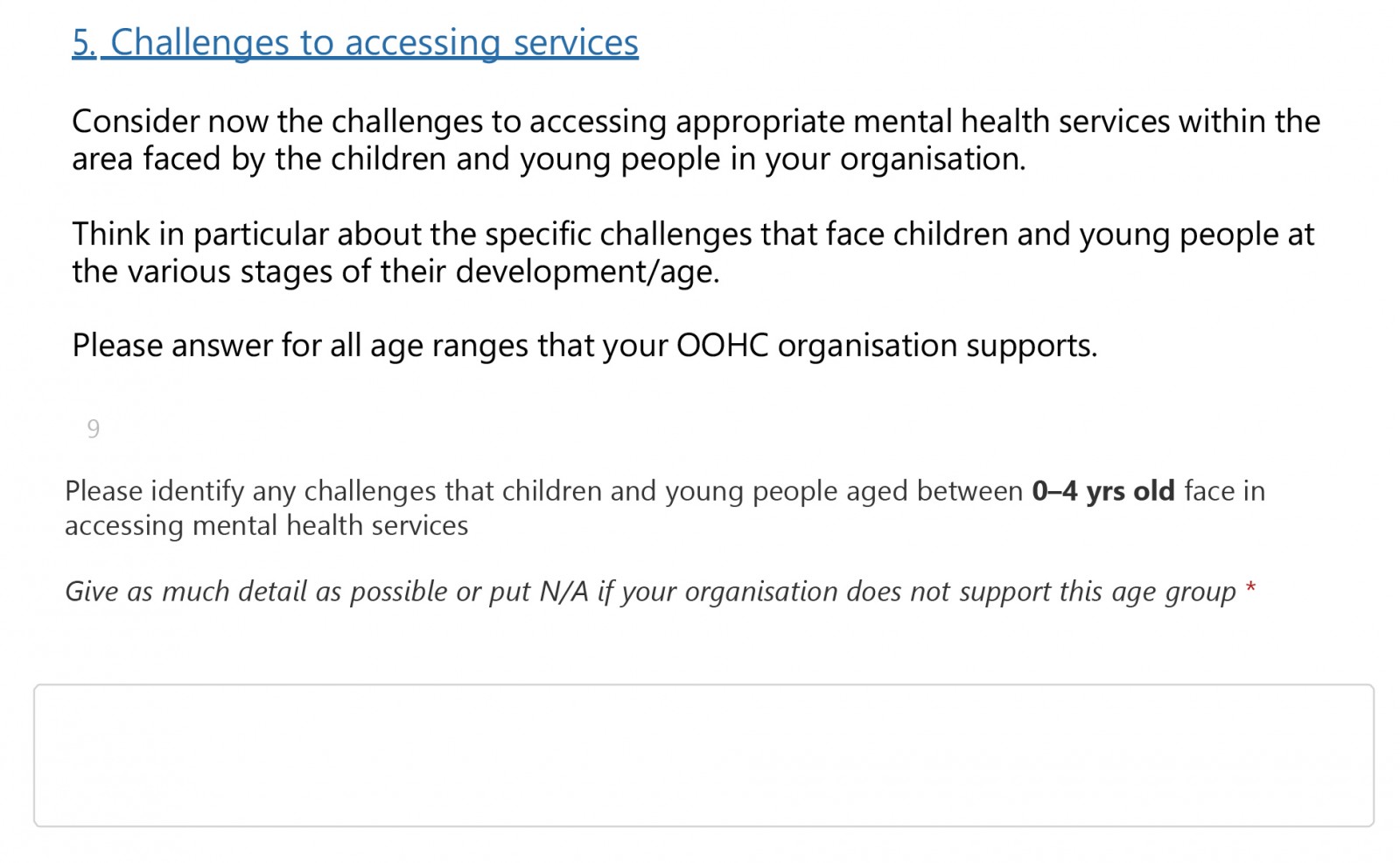

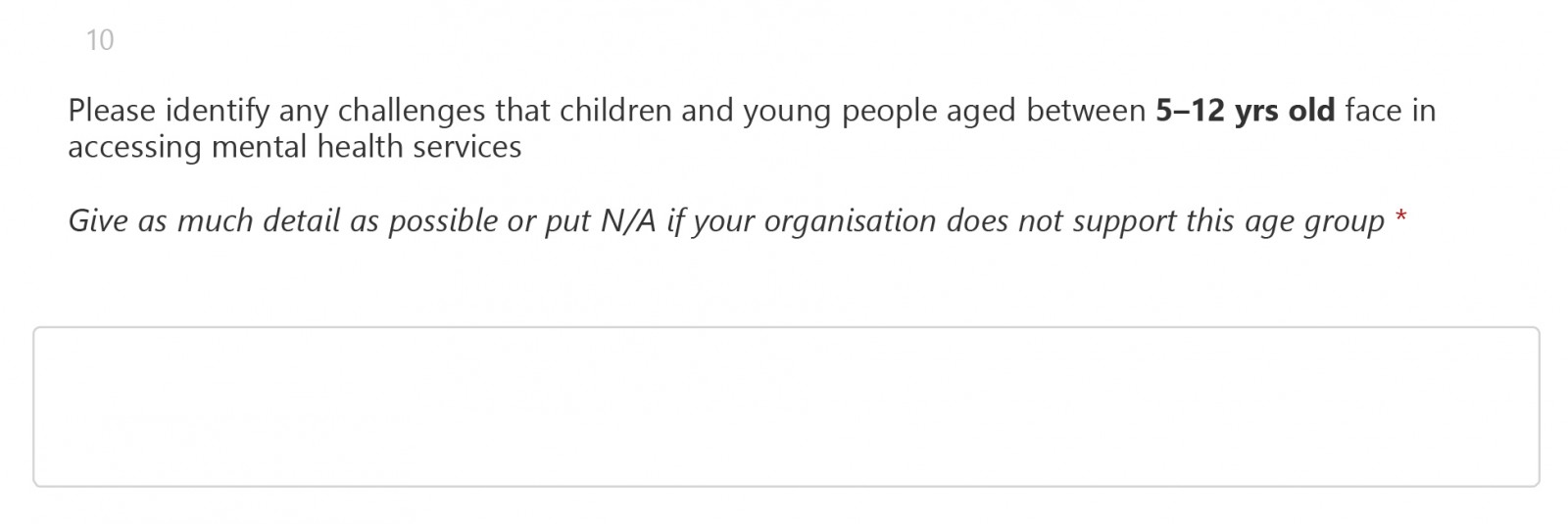

Audit 1 sought information on two key areas:

1. The challenges organisations face in accessing mental-health services and support for children and young people in OOHC in the following cohorts:

- Children aged 0–3 years;

- Children aged 9–12 years; and

- Children and young people with acute suicidal and/or self-harming behaviour.

2. The experience of using mainstream and specialist mental-health services.

Audit 2

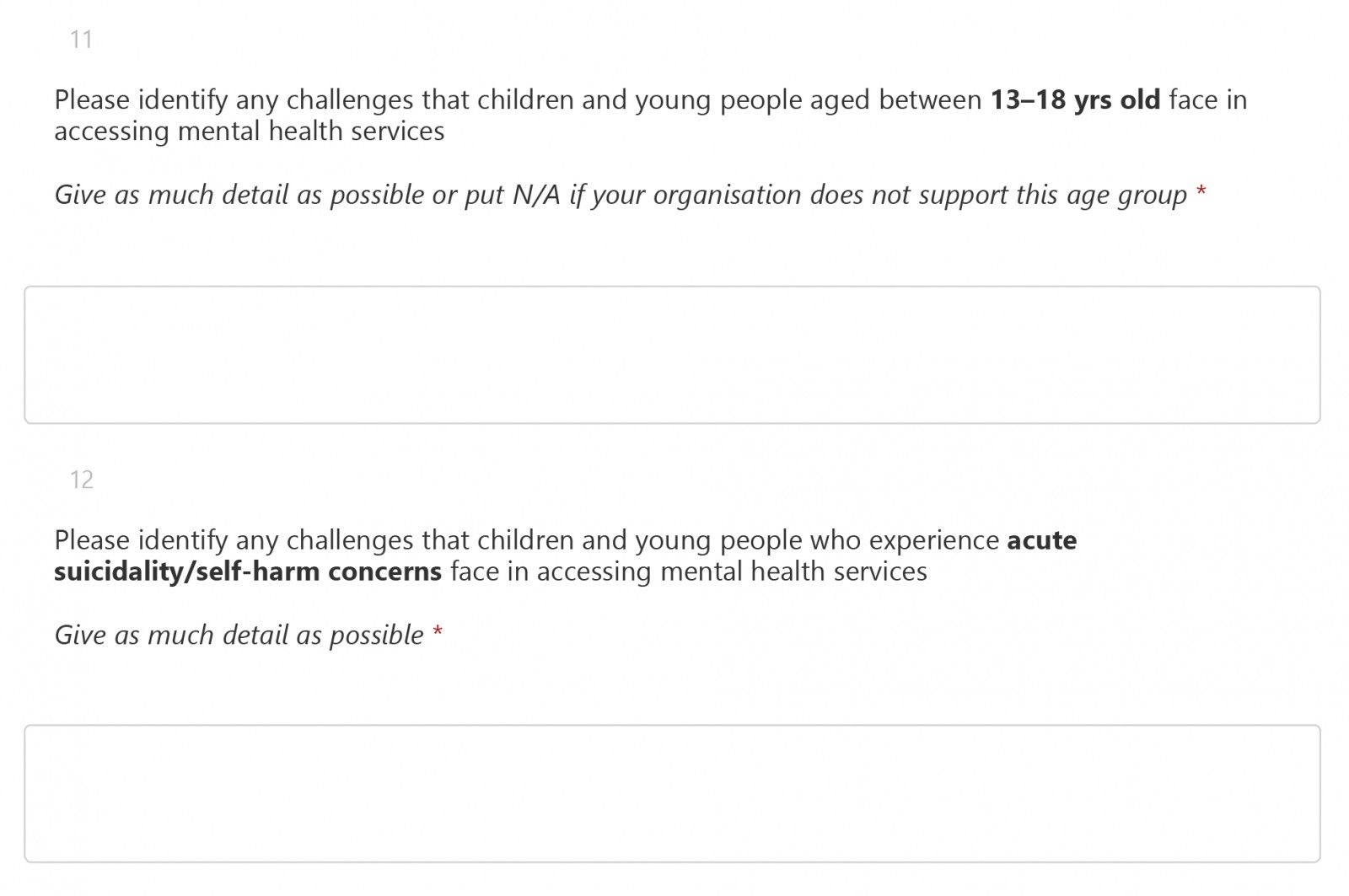

The Collective undertook an iterative approach to the development of a second audit tool. To build on the information provided by Collective members through Audit 1, a second tool was developed that aimed to collect a wider range of data more systematically, using a mix of closed and open-ended questions (see Appendix 2 for Audit 2 questions). The two questions from Audit 1 were repeated in this more comprehensive audit tool along with a series of other, more in-depth questions.

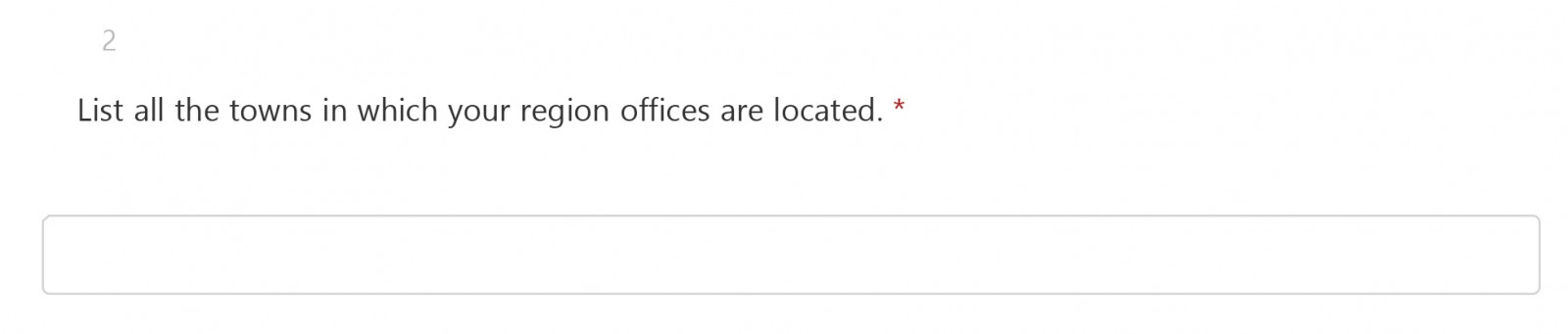

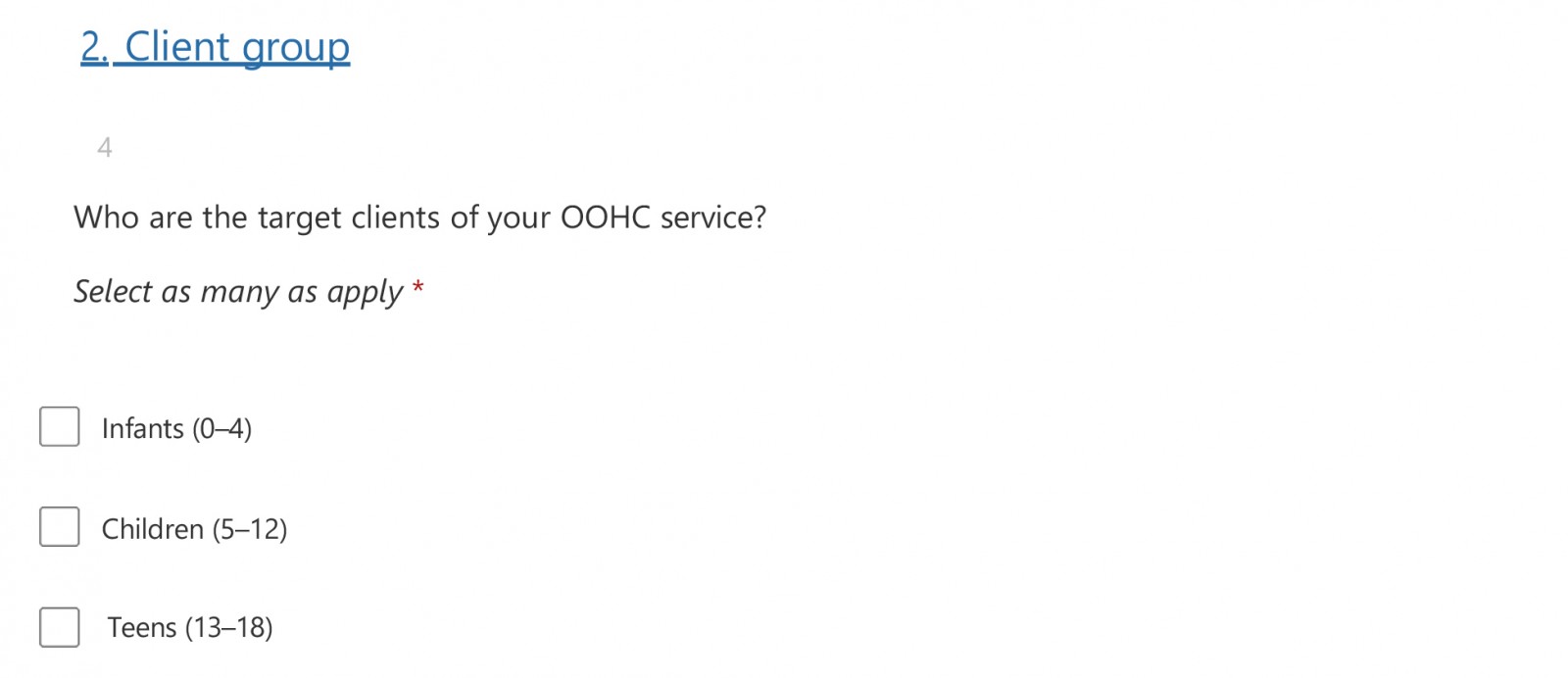

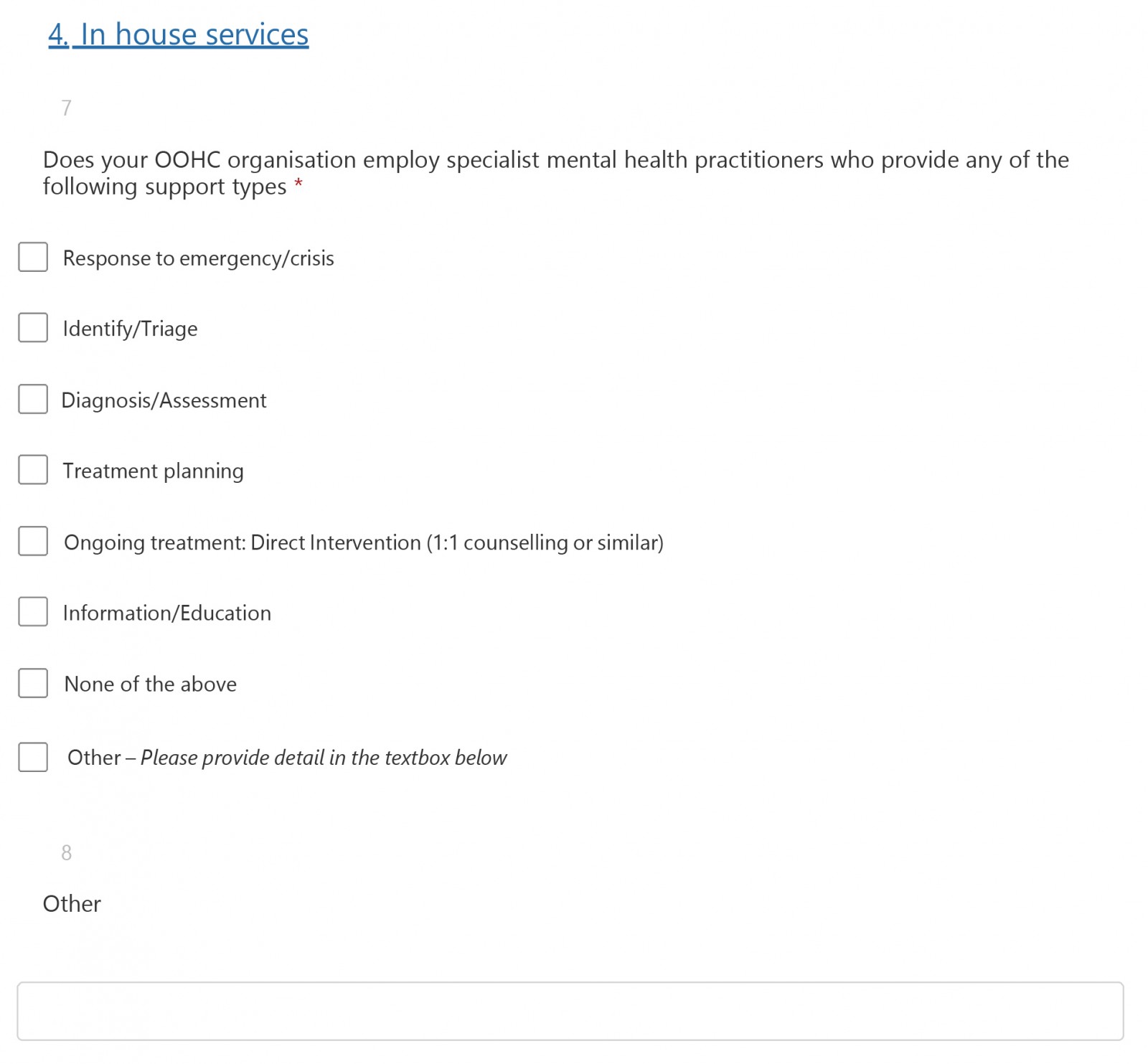

The new questions were tested with members of the Collective working group for relevance and completeness prior to dissemination. Specific areas that were explored in this initial test included the categorisation of common mental-health concerns experienced by this cohort and respondent prompts related to barriers. The resultant audit tool was an original creation by the Collective drawing on real-life experiences and the existing literature. Audit 2 asked identifying information about the OOHC service providers, where its offices were located and its client group by age cohort. Agencies were also asked to identify any in-house services that it employed specialist mental-health practitioners to provide.

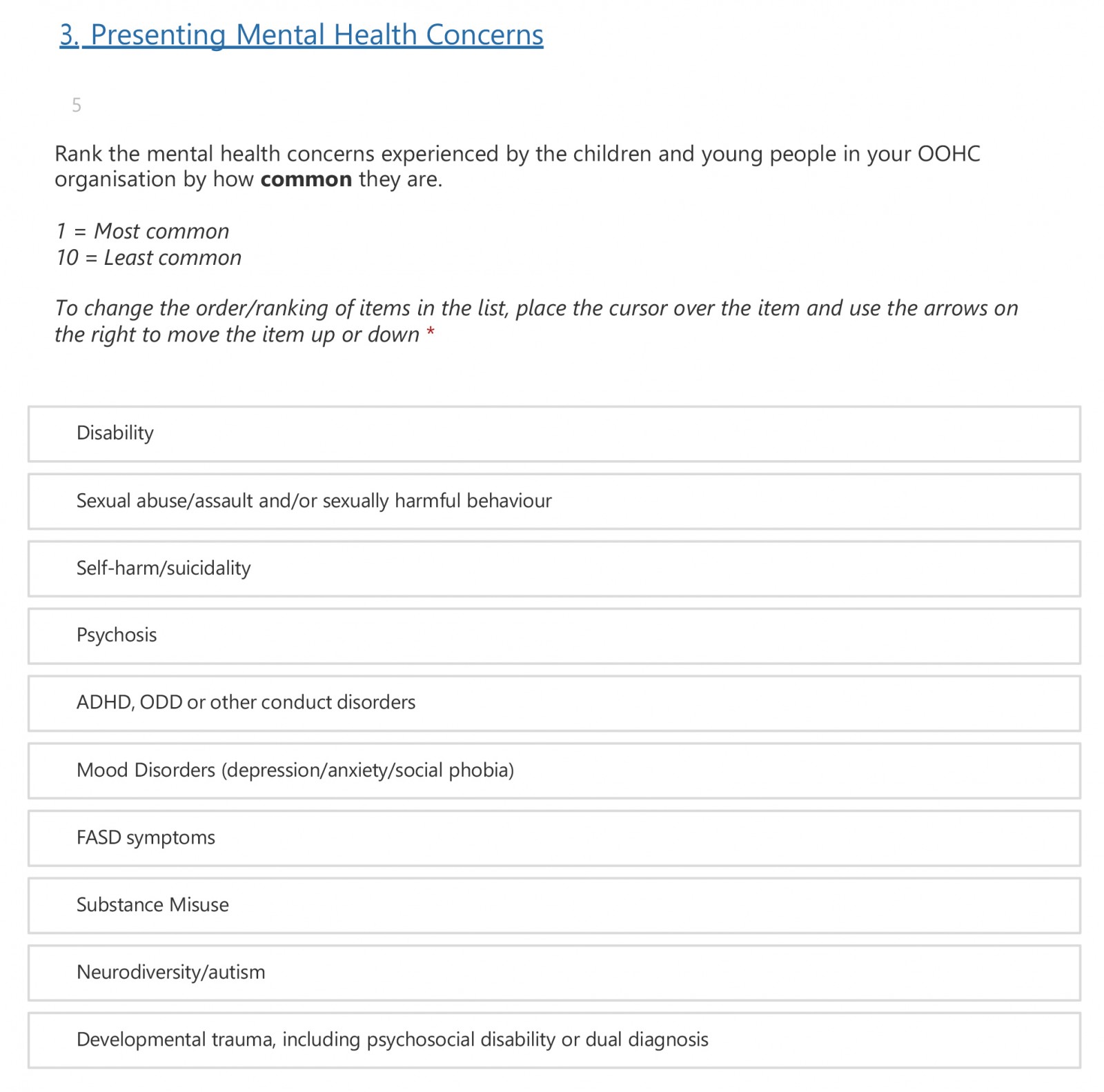

In addition, respondents were asked to rank the commonality of ten mental-health concerns experienced by children and young people in their care. These are listed in alphabetical order:

- Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), Oppositional Defiance Disorder (ODD) or other conduct disorders;

- Developmental trauma, including psychosocial disability or dual diagnosis;

- Disability;

- Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) symptoms;

- Mood disorders (depression, anxiety or social phobia);

- Neurodiversity or autism;

- Psychosis;

- Self-harm and/or suicidality;

- Sexual abuse, assault and/or sexually harmful behaviour; and

- Substance misuse.

This question also provided respondents the opportunity to add mental-health concerns not listed and to share commentary on their inclusion.

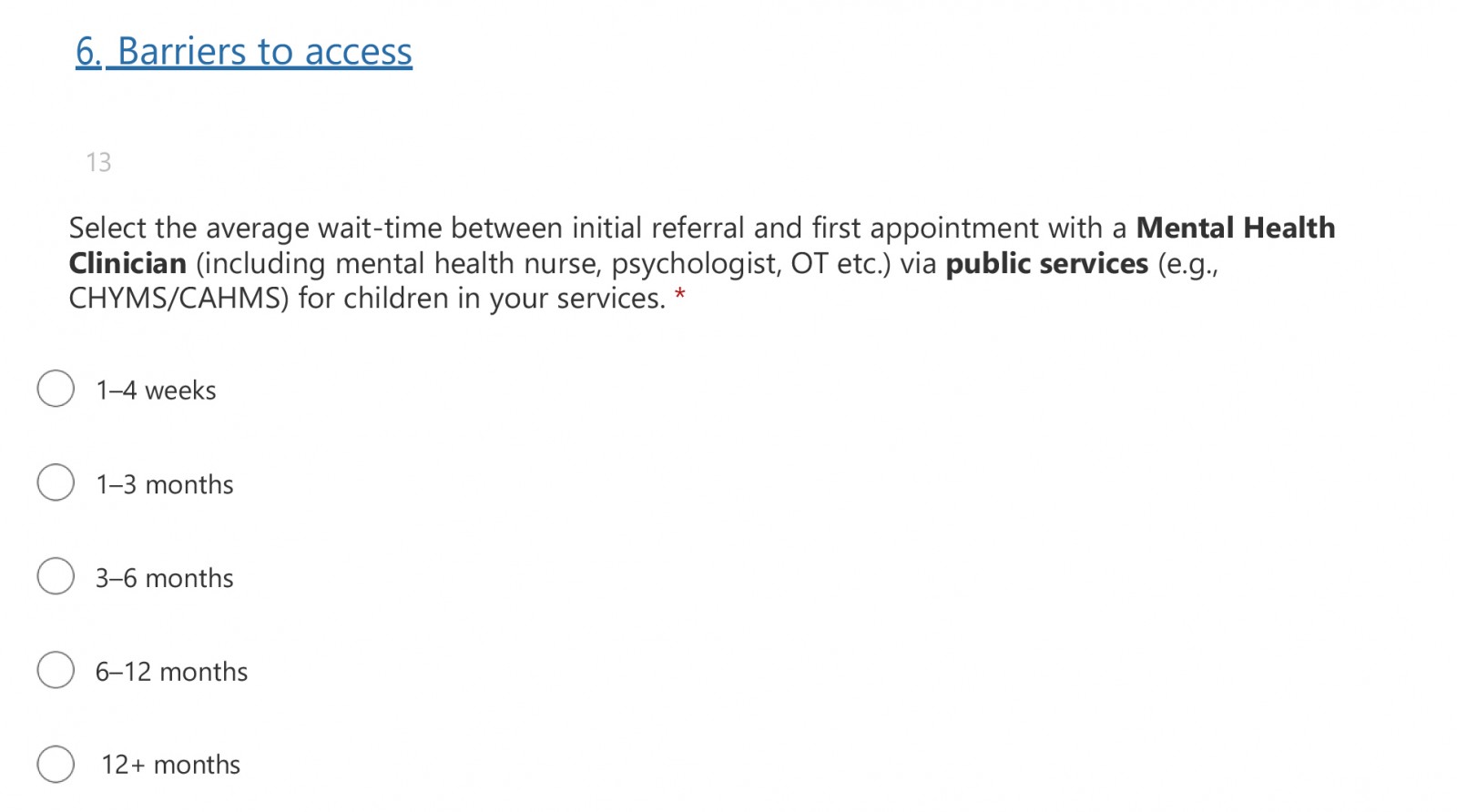

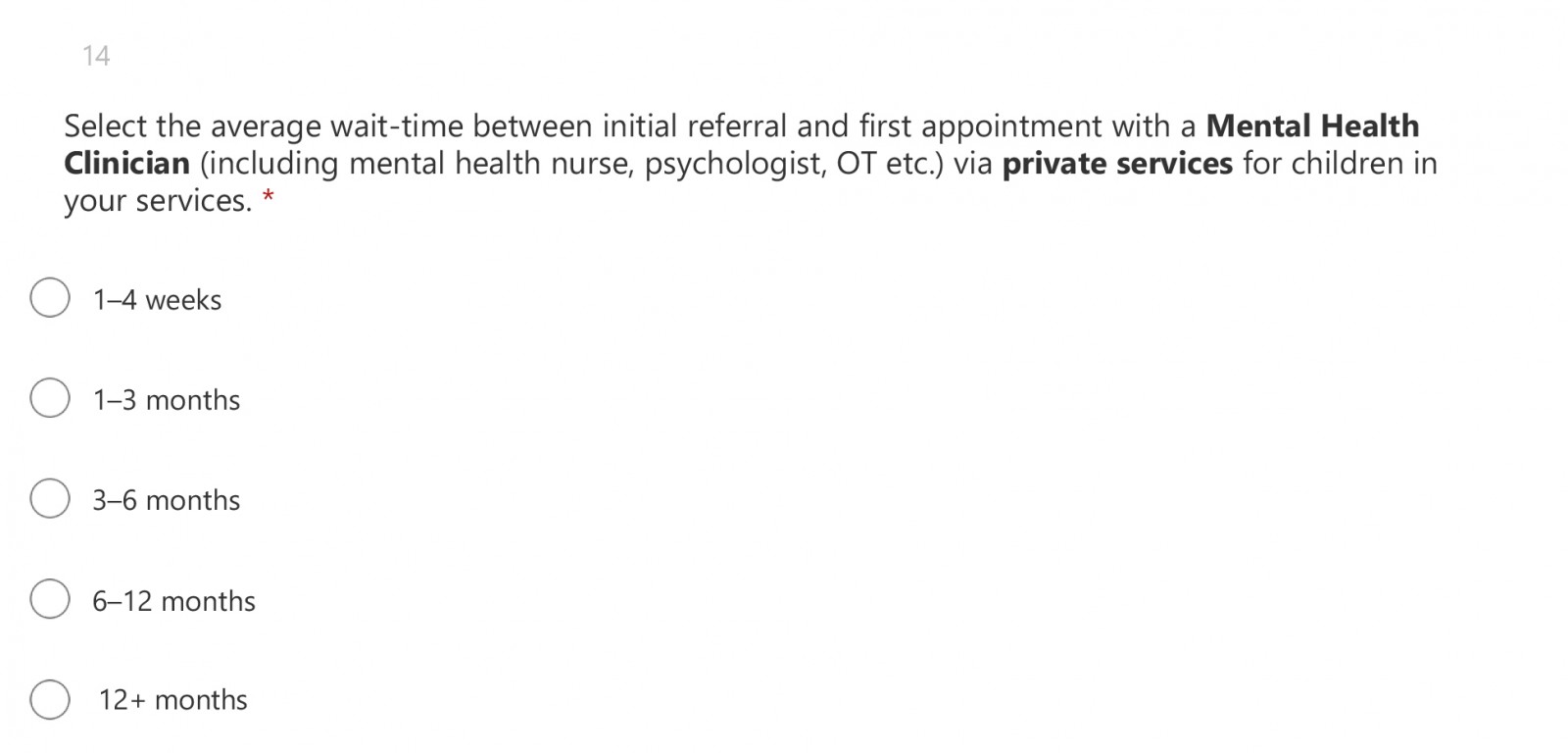

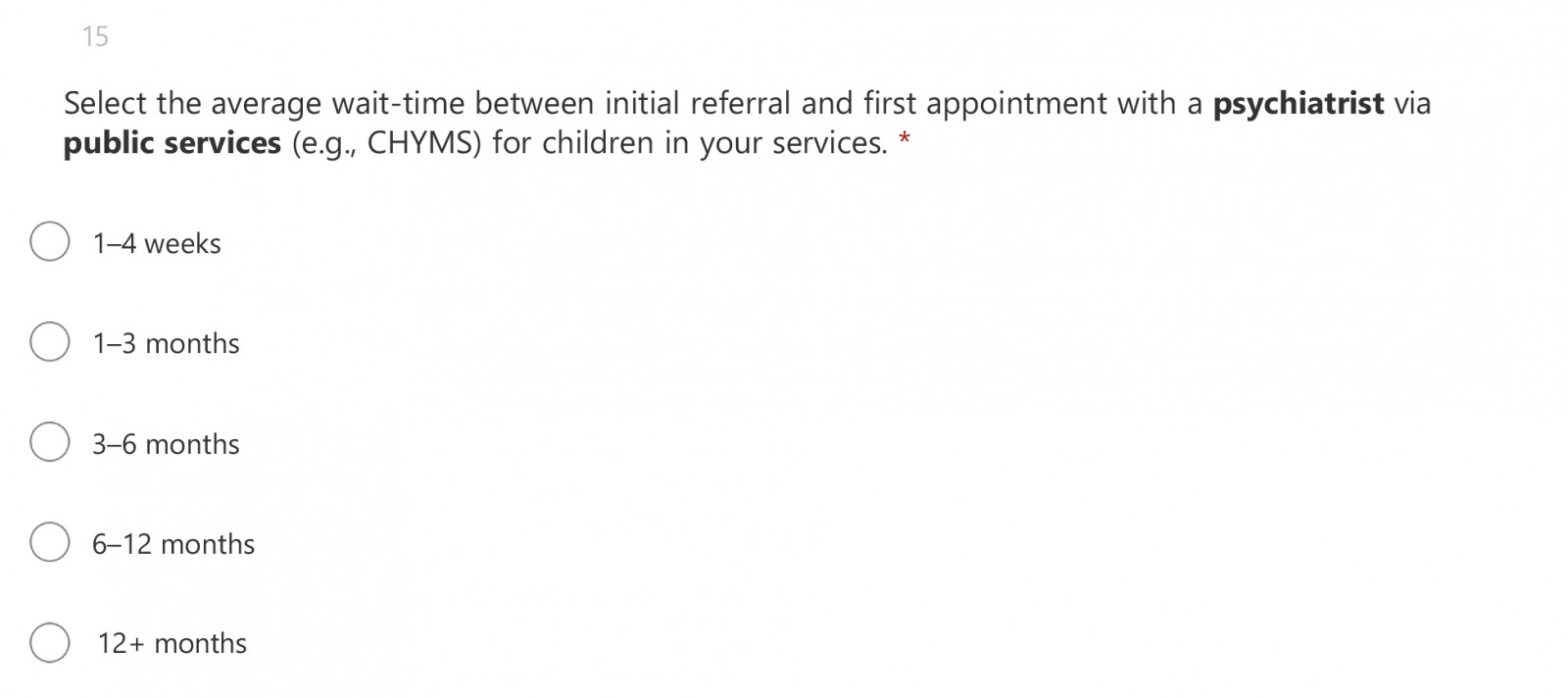

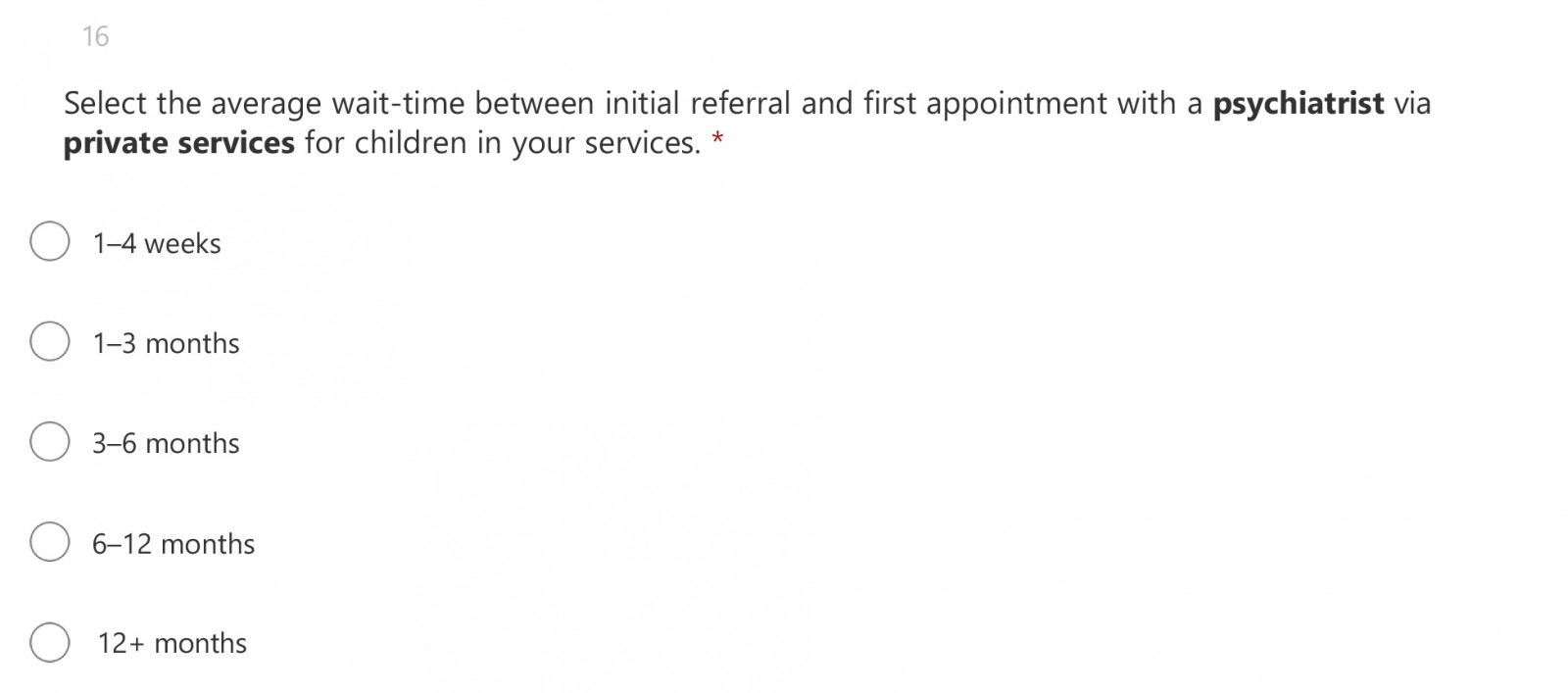

Respondents were also asked specifically about average wait times for appointments with mental-health clinicians and psychiatrists via both public and private services.

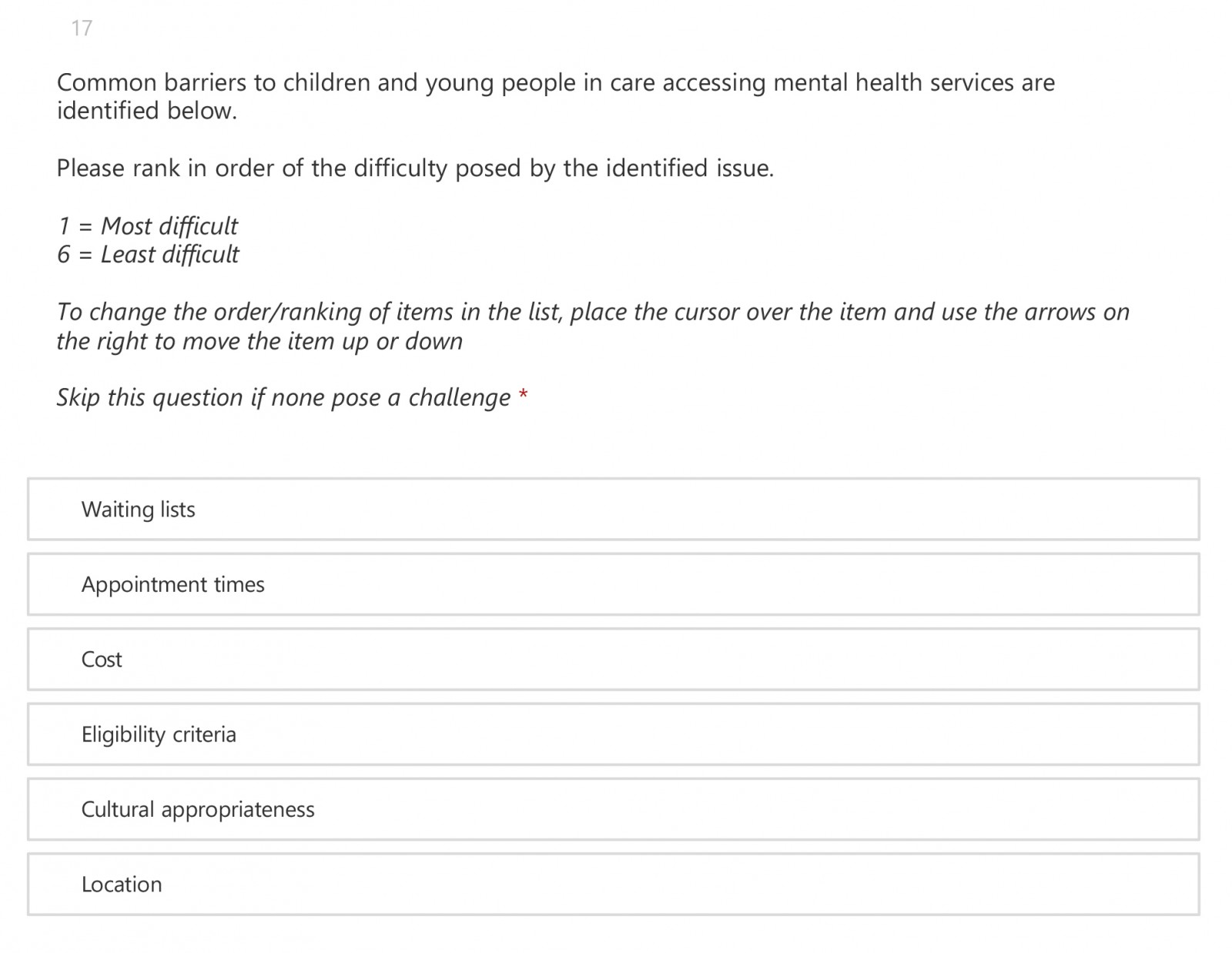

Finally, respondents were asked to rank a list of pre-determined barriers to service access, in order of difficulty posed by the identified issue. They included:

- Appointment times;

- Cost;

- Cultural appropriateness;

- Eligibility criteria;

- Location; and

- Waiting lists.

Agencies were also offered an opportunity to identify any barriers to, or gaps in access to, mental-health support not already provided in the audit tool.

Data collection and analysis

For Audit 1, we sent an email to OOHC service providers that were member agencies of the Collective asking for responses to those questions via email. This was completed in September 2022.

Data were analysed using a grounded theory approach, whereby theory is generated from the data rather than using data to test hypotheses and verify theory (Charmaz, 2006). In this instance, the method was used to identify the main categories of issues identified by participants. These were: assessment and/or diagnosis; availability of services; treatment; cooperation and/or coordination; disability and/or National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) complexities; young people’s engagement; and working with carers and/or families. The identified categories of issues informed the development of the second audit tool.

For Audit 2, we sent a link to an online platform where we hosted the audit questions to a nominated representative respondent for each agency that had offered to participate. The audit was conducted between August and October 2023.

We undertook a thematic analysis of the qualitative data and use quotes here to illustrate the findings of this project.

To identify the most common presenting mental-health concerns, the three most frequently identified mental-health concerns were combined to indicate issues of concern for most agencies and therefore children and young people.

Ethics approval was not considered warranted for the conduct of audits that assessed practice in a real-world scenario.

Results

Of the 15 OOHC service providers who provided information on their experiences, five member agencies of the Collective responded to both audits because they provide services in the supplementary regional area. All the agencies responding to the audits operate services in metropolitan, regional and rural areas of New South Wales.

Mental-health concerns experienced by children and young people in care

All the mental-health concerns identified in the second audit tool were categorised as commonly experienced, although they ranged in frequency.

Respondents described the most commonly experienced mental-health concerns as:

- The effects of developmental trauma, including psychosocial disability or dual diagnosis (for 9 of 11 agencies);

- Mood disorders such as depression, anxiety and/or social phobia (ranked in the top three concerns by 7 of 11 agencies); and

- ADHD, ODD or other conduct disorders (ranked in the top three concerns by 6 of 11 agencies).

Issues with assessment and/or diagnosis

Many agencies reported on the difficulty in finding mental-health practitioners with the right skills to assess and treat children and young people in care. Specifically identified were the limitations of practitioners' understanding of complex trauma and its manifestation in a child’s behaviour, and practitioners’ limited understanding of the OOHC context in which children are living:

This cohort is often too complex for the public mental health service. They are discharged with little to no follow up support from the health service. They are also considered too high risk for private mental health services. (Audit 1)

The most common type of therapy is CBT [cognitive behavioural therapy] Talk therapy which may be a mismatch for children with a strong trauma history (due to the reliance on cognitive/verbal functioning). (Audit 1)

Several agencies identified significant and frequent experiences of diagnoses of children that did not consider their trauma history.

Health practitioners […] fail to understand trauma responses and believe that action is ‘behavioural’ (attention seeking) rather than a physical pain response to emotional trauma. (Audit 2)

As with younger children, mental health clinicians seeing adolescents with self-harming and injurious behaviours, and suicidality, don’t understand prodromal symptom for children in out of home care, nor have a strong understanding of trauma (nor domestic violence, sexual assault or substance use). (Audit 1)

Other agencies reported on health professionals’ inadequate understanding of the impact of developmental trauma, including children being medicated instead of being given access to forms of therapy that would work to ameliorate the underlying developmental trauma presentation:

We have mixed experiences of receiving accurate diagnoses which take the child’s trauma history into account. We have collated a list of trauma-informed providers, so if we are consulted when families are seeking mental health assessment, we can direct them to suitable services. Many other providers lean toward behaviour-focused diagnoses (e.g. ODD, ADHD) without factoring in the impact of the child’s experience of felt safety in relationships and the world … (Audit 1)

Health specialists’ ability to distinguish between trauma and ADHD, ODD etc [is a challenge] (Audit 1)

Agencies reported that mental-health-service practitioners frequently refused mental-health services to children and young people in OOHC on the grounds of a child’s symptoms being seen as behavioural rather than mental-health issues:

When it comes to mental-health specific services, like entry to CAMHS [Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services], or children who are seen at ED [emergency department] with mental health symptoms (like self-harm), services are denied by frequently touting – ‘it’s behaviour not mental health’. (Audit 1)

Our young people are being labelled as ‘frequent flyers’ in the hospital system and their mental health needs are minimised. Emergency departments aren’t equipped for our children and young people’s complexity and this inevitably leads to inaccurate assessment. At intake in our hospitals and with CAMHS (often times due to stigma of being an OOHC kid) psychiatric nurses or clinicians either minimise the risk or put symptoms of psychosis or deteriorating mental health down to trauma or drug use … (Audit 1)

This judgement was similarly applied to all age groups. Agencies noted this in relation to teenagers who were self-harming:

Our young people in this age range face significant barriers to accessing mental health services particularly during after-hours presentation at hospitals and CAMHS with acute suicidal/self-harm concerns. Most often our young people and staff are told that the issues are behavioural and not mental health related regardless how often a young person has self-harmed or stated that will take their own life. We have numerous examples of young people being turned away from hospital and hospital staff making complaints about our staff when we strongly advocate for young people to be admitted. (Audit 2)

But this was not restricted to adolescents, or to specific behaviours such as self-harm. In relation to children, agencies also frequently observed mental-health services’ refusal to treat them on the grounds of the child’s symptoms being seen as ‘behavioural’ rather than a mental-health issue:

The system agreeing that mental health is an issue for this age group and getting diagnosis and or treatment is tricky. Often kids are just labelled with all the D’s: ADD ODD ADHD FASD or just referred to being trauma and prescribed meds. (Audit 2)

Agencies also identified barriers to services arising from misunderstanding infants’ behaviour:

[They are] misdiagnosed or labelled incorrectly as having anxiety, just being ‘naughty’ or ‘fussy/high needs’, having early signs of autism or as ‘the good baby’ – when they are clearly dissociative and shut down or have non-organic failure to thrive’. (Audit 1)

Many agencies observed that this minimisation leads to children being missed or denied a service when early intervention could shift their functioning to a healthy trajectory before they reach adolescence.

Scarcity of appropriate and timely services

When asked to rank the difficulty resulting from common barriers to services, nine of the 11 respondents identified waiting lists as the number one issue for their agencies. Agencies were asked an open question about the specific challenges to accessing appropriate mental-health services for each of the age cohorts and for children and young people experiencing acute suicidality and/or self-harm concerns.

Every agency identified as a key issue the scarcity of mental-health services.

Agencies reported that it was quicker to see a mental-health clinician or psychiatrist via public services, although this can still be a waiting time of more than 12 months. It is possible that access to a mental-health clinician via public services within 4 weeks of an initial referral would be in an acute hospital setting, but this can’t be determined from our audit data. Psychiatrist waiting times are long: no-one had an appointment within 4 weeks of referral:

It is extremely difficult to access child and adolescent psychiatrists in a timely manner where this is needed. If waitlists are open, they tend to be many months long. Trauma-informed paediatricians with current availability are also hard to come by. (Audit 1)

They also identified access to all forms of therapeutic services as problematic:

[The issue is] appropriate mental health specialists who understand complex trauma who provide appropriate services and do not have long wait lists. (Audit 1)

Across the board there are access and resourcing issues to appropriate therapeutic services […] there are ‘wait-list’ problems and […] some services and private practitioners have just closed their books and are just not taking new clients at all – even in capital cities … This includes services that provide OT, trauma-specific psychology and social work, child protection counselling, play therapy, animal assisted therapy, family therapy services, parent–child intervention services and harmful sexual behaviour treatment services. (Audit 1)

Delays in diagnosis and treatment have obvious implications for the healing and recovery of mental-health challenges experienced by children and young people in care. In particular, opportunities for early intervention are missed:

Early access is required for comprehensive, multidisciplinary assessment and intervention to prevent further trauma (including by the service system). (Audit 1)

The limited availability of youth health and mental-health services, particularly in rural and remote areas of Australia, is well known and not specific to children and young people in OOHC, despite the problems it can cause (Policy Writing Group 2020):

Lack of choice re services in most areas – there is often one service […] which takes a long time to get into. (Audit 2)

There are not many services in the areas that specialise in out of home care and a lot do not understand the needs of the young people. The waitlists are very long or often books are closed. (Audit 2)

The exclusionary criteria of services can present barriers to access:

Headspace (low/moderate need) vs CAMHS (high need), creates a gap and many YP in OOHC are stuck between the two as they get screened out of both. (Audit 1)

Lack of culturally appropriate services is also a barrier to appropriate treatment:

CAMHS regionally has no [Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander] clinicians and frequently they diagnose children who are off country and/or experiencing spiritual phenomena as having psychosis or mental illness. This is true of children in the older age [group] also. (Audit 1)

[What is needed is an] approach to assessing the breadth of individual, family, community, cultural issues – understanding the child’s history is important through [a] culturally responsive lens. (Audit 1)

The limited capacity of the health system to provide timely and appropriate services to children and young people in care was cited as the reason for OOHC service providers developing in-house services:

We built our internal clinical services out of the need for our clients to access informed, well-trained professionals who are knowledgeable in OOHC, significant behaviour concerns and specific diagnoses, within an appropriate timeframe. This was because there was a gap in the public system and children and young people were not being treated as soon or as often as they should for appropriate mental health care e.g. could not get an appointment for a medication review in a timely manner when the young person’s condition changed. (Audit 2)

Particular difficulties arise in finding well-qualified professionals for children and young people with disability who have mental-health concerns:

Another significant issue is that since the introduction of the NDIS, there has been an increase in waiting times and most services we have tried to engage lack in training and sophistication that is required to work with our complex cohort in OOHC. Also, they are only willing to offer basic services such as traditional counselling rather than assessments etc … (Audit 1)

Misunderstanding out-of-home care

Not only are agencies having difficulty finding services and practitioners with the right skills and availability, but they are also experiencing problems that arise from practitioners not understanding the OOHC system or simply refusing to work within its parameters.

Many agencies reported on the misunderstanding of what is called ‘intensive therapeutic care’ in New South Wales:

Many public services do not have a solid understanding of the nature of [OOHC] and residential care. CAMHS often closes referrals very quickly when realising that there are internal therapeutic supports, but do not tend to realise that ‘therapeutic supports’ does not mean treating clinician. We would often like to see a greater level of collaboration with clinicians accepting referrals for the YP within our residential services. (Audit 2)

Frequently we find that where [we are] seen to be involved with a child, mental health services characterise us as a ‘protective factor’ and the child as already receiving a service (even if it’s just case manager without any formal therapeutic training). This becomes a reason to delay a service […] or deny a service altogether as we are characterised has having mental health expertise – even for children experiencing delusions and hallucinations, or evidence of early onset symptoms for schizophrenia. (Audit 1)

Due to limited mental health resources, young people with suicidal/self-injuring behaviour may be referred back to their OOHC case manager for support/supervision by youth workers, rather than being admitted, as may occur for children with the same presentation who are not in OOHC … (Audit 1)

Several agencies reported on the difficulties of maintaining services for children whose placement in OOHC was unstable:

The only supports offered are generally safety planning and crisis management. Often this has also been denied if the young person is out of placement because ‘there is no one to put on the safety plan.’ (Audit 1)

Some community and funded mental services also won’t work with a child and young person unless they are in stable placements which is an ongoing issue when placement breakdowns occur and a child moves placement. (Audit 1)

There are significant difficulties arising from mental-health practitioners’ refusal to provide information to OOHC agencies that is necessary for these agencies to comply with contractual requirements:

We have also had many issues with practitioners not willing to comply with our contractual and compliance requirements around medication and practices, flatly refusing to complete reports or provide adequate information to process restrictive practices approvals and maintain adequate records. (Audit 1)

Private providers are also reluctant to feedback to us as the statutory service, even when we ask for progress reports, hiding behind ‘confidentiality to the client’ clauses. (Audit 1)

There seems, in fact, to be a complete misunderstanding by some health professionals of what is meant by a child being in out-of-home care:

A ‘unique’ problem we’ve encountered is some paediatricians refuse to speak to case managers about mental health medication etc. because they don’t recognise the agency as the parent, despite the statutory Parental Responsibility function being delegated to us … (Audit 1)

Summary of findings

Children and young people in the OOHC system experience a wide range of mental-health concerns. Our findings suggest that symptoms of complex and/or developmental trauma are commonly experienced, but are seemingly not well understood by mental-health professionals. This echoes advocacy efforts by Tarren-Sweeney (2010). OOHC service providers report that a frequent response by health professionals, even when a child or young person is experiencing acute self-harming or suicidal behaviour, is to label and treat the issues as behavioural rather than mental ill-health. The minimising of mental-health issues becomes a barrier to accessing appropriate mental-health services because services are denied or delayed.

An additional barrier to the provision of timely and appropriate mental-health services is the scarcity of appropriate mental-health services for children and young people living in care. Access to all forms of therapeutic services is constrained by few practitioners, long waiting lists or no services at all. Even when services exist, further barriers present themselves in terms of impossibly tight criteria for clients and culturally inappropriate services. Agencies also reported practitioners finding the treatment of these children and young people too complex, due both to their limited understanding of complex trauma and their limited understanding of the OOHC system.

The structure and legal requirements of the OOHC system itself present a barrier to children and young people in its care accessing appropriate services. There are contractual and compliance requirements for medication and restrictive practices that include reports and approvals. Agencies noted that health professionals were unwilling to provide the necessary reports or adequate information, with the rationale sometimes being patient confidentiality. This is a misunderstanding of the statutory parental responsibility delegated to OOHC service providers.

A further misunderstanding is of the level of therapeutic care and support available to young people living in residential care in New South Wales and the role of an OOHC case manager. Agencies believe that children in care are discharged or refused hospital admission more frequently than those who are not in OOHC because clinicians see the agency as a protective factor and the case manager as sufficient support.

Discussion

There is extensive literature on the poor mental-health outcomes for children and young people in OOHC. For example, analysis of population prevalence shows a high rate of maltreatment and childhood adversity in people with experience of OOHC (Harris et al., 2024a), and the association of high intensity of maltreatment with higher likelihood of experiencing mental-health disorders like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety and depression (Harris et al., 2024b). The Australian Child Maltreatment Study (ACMS) revealed that people with an experience of OOHC experienced more types of maltreatment than people in the general population who had experienced maltreatment. They also reported higher rates of PTSD, generalised anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder than Australians who had experienced maltreatment but had not experienced OOHC (Mathews et al., 2023).

The present study confirmed that mental-health concerns, particularly developmental trauma, were commonly identified by OOHC service providers. Our findings about difficulties in accessing appropriate and timely mental-health supports and services is also in line with existing research. For example, McLean and colleagues reported that:

Mental health is the area of most concern for this population. Most carers thought that the mental health needs of children in their care had not been well assessed. The largest gap between carer-perceived need and service use was in mental health, and mental health services were the hardest to access. (McLean et al., 2021: p. 137)

The vulnerability of children and young people in care is recognised not only in research but in existing national frameworks and strategies in Australia and the work of the Collective is carefully aligned with these.

In particular, our aims are consistent with the National Children’s Mental Health and Wellbeing Strategy (National Mental Health Commission, 2021). The media statement announcing the strategy states that it provides

… a framework to guide the development of a comprehensive, integrated system of services to maintain and support the mental health and wellbeing of children aged 0–12 and their families. (Hunt, 2021)

One of the eight foundational principles of the Strategy’s development is that service delivery should be ‘needs based, not diagnosis driven’ – i.e., based on individual needs with a reduced focus on requiring a diagnosis to access services (National Mental Health Commission, 2021: p. 27).

Discussion within the Collective about the misunderstanding of the OOHC system by health professionals was confirmed by audit findings. There is clearly a need for much closer understanding and collaboration between these two service systems (Barth et al., 2020; Kerns et al., 2014). This concern is also reflected in the international literature, with a particular focus on the need for clarity about roles, responsibilities and authorisations (Royal Australasian College of Physicians, 2023). A recent Australian study of the mental-healthcare needs of care leavers argued for an urgent increase in skills across sectors to identify and appropriately respond to the unique needs of children and young people in OOHC (Mendes & Chaffey, 2024). Bunger et al. (2021) similarly noted the persistence of ‘substantial unmet mental-health service needs’ (p. 8) in this group. It is a system failure issue that, across both the OOHC and the mental-health systems, we continue to struggle to provide for the mental-healthcare needs of this under-served group.

Limitations

While the findings of the Collective’s study are broadly consistent with the literature, respondents comprise only 15 OOHC service agencies and the audits focused only on the provision of mental-health services in New South Wales. This limits the generalisability of the findings.

This project does not specifically include Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives on social and emotional wellbeing, mental-health disorders and healing. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children are vastly over-represented in the OOHC system and in New South Wales there is considerable work underway to transition Aboriginal children to the care of Aboriginal community-controlled OOHC agencies. Determining the views of these agencies on access to appropriate and timely services for Aboriginal children should be an important component of any further research.

Suggestions for action

There is a clear need for more mental-health-service resources and funding and a strategy to address the mental-health needs of children and young people in OOHC. The Collective recognises the complexity of decisions faced by Commonwealth, state and territory governments in the allocation of increased funding for mental-health and health services. Based on its audit findings, the Collective proposes three achievable and practical actions that would immediately lead to the reduction of barriers to more appropriate and accessible provision of mental-health and wellbeing services for children and young people in care while broader funding allocation is considered.

Priority access and an increased focus on prevention and early intervention, including to preventative alternative and adjunct therapies, are strategies that address the barriers presented by scarce services and long wait lists.

1. Priority access

Children and young people in care should be given priority access to mental-health services and resources through specialist youth services (CAMHS) and both Commonwealth-funded services (primary health networks) and state- or territory-funded services (local health networks).

2. Prevention and early intervention

Increased focus should be given to preventative and early intervention mental-health support for children and young people in care. This should include improved funding of, and access to, evidence-based preventative alternative and adjunct therapies (including, for example, music therapy, equine therapy and play therapy, where there is evidence to support their efficacy).

Improving shared understanding is a strategy to address barriers presented by misunderstanding and lack of collaboration.

3. Shared understanding

Out-of-home care service providers and state and territory health systems and personnel need to develop a clear shared understanding of the needs of children and young people in care, the appropriate language to use to describe their experiences and needs, the impact and implications of complex trauma, and what is meant by therapeutic out-of-home care. This could be achieved through a dedicated policy and multi-agency or sector agreements that set out expectations and roles.

Conclusions

Connecting children and young people in care with timely and appropriate mental-health supports through systemically addressing barriers is essential for avoiding or mitigating the long-term negative mental-health outcomes that are otherwise the likely consequence.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the member agencies of the Children in Care Collective for their support of, and contribution to, this project and, particularly, the project team for their contributions to the development of the audit tools. We also thank all the out-of-home care service agencies who completed audits.

Funding statement

The Children in Care Collective funded this project as part of its work advocating for therapeutic mental health support and healing for all children and young people in out-of-home care.

Conflicts of interest

Nothing to declare.

References

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2021). Child protection Australia 2019–20. Child Welfare Series No. 74. Canberra: AIHW. aihw.gov.au https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/c3b0e267-bd63-4b91-9ea6-9fa4d14c688c/aihw-cws-78.pdf.aspx?inline=true

Barth, R. P., Rozeff, L. J., Kerns, S. E., & Baldwin, M. J. (2020). Partnering for Success: Implementing a cross-systems collaborative model between behavioral health and child welfare. Children and Youth Services Review, 117, 104663. DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104663

Bunger, A. C., Maguire-Jack, K., Yoon, S., Mooney, D., West, K. Y., Hammond, G. C., & Kranich, C. (2021). Does mental health screening and assessment in child welfare improve mental health service receipt, child safety, and permanence for children in out-of-home care? An evaluation of the Gateway CALL demonstration. Child Abuse & Neglect, 122, 105351. DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105351 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34628151

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing Grounded Theory A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage Publications.

Devlin, R., Jairam, R., Asghari, M., & Eapen, V. (2022). Does assertive mental health care make a difference to children in out-of-home care? A pilot study. Developmental Child Welfare, 4(1), 73–93. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/25161032211064644

Green, M. J., Hindmarsh, G., Kariuki, M., Laurens, K. R., Neil, A. L., Katz, I., Chilvers, M., Harris, F., & Carr, V. J. (2020). Mental disorders in children known to child protection services during early childhood. The Medical Journal of Australia, 212(1), 22–28. DOI https://doi.org/10.5694/mja2.50392 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31680266

Harris, L. G., Higgins, D. J., Willis, M. L., Lawrence, D., Mathews, B., Thomas, H. J., Malacova, E., Pacella, R., Scott, J. G., Finkelhor, D., Meinck, F., Erskine, H. E., & Haslam, D. M. (2024a). The prevalence and patterns of maltreatment, childhood adversity, and mental health disorders in an Australian out-of-home care sample. Child Maltreatment, 30(1), 42–54. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/10775595241246534 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38627990

Harris, L., Higgins, D. J., Willis, M., Lawrence, D., Meinck, F., Thomas, H. J., Malacova, E., Scott, J. G., & Haslam, D. M. (2024b). Dimensions of child maltreatment in Australians with a history of out-of-home care. Child Maltreatment. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/10775595241297944 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39499703

Herrman, H., Humphreys, C., Halperin, S., Monson, K., Harvey, C., Mihalopoulos, C., Cotton, S., Mitchell, P., Glynn, T., Magnus, A., Murray, L., Szwarc, J., Davis, E., Havighurst, S., McGorry, P., & Tyano. In S (Ed). Kaplan, I., Rice, S., & Moeller-Saxone, K. (2016). A controlled trial of implementing a complex mental health intervention for carers of vulnerable young people living in out-of-home care: The ripple project. BMC Psychiatry, 16(1), 436. DOI https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-1145-6 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27927174

Hunt, G. (2021, 12 October). Australia launches world’s first children’s mental health and wellbeing strategy. Media Release. Canberra: Department of Aged Care, Australian Government. health.gov.au https://www.health.gov.au/ministers/the-hon-greg-hunt-mp/media/australia-launches-worlds-first-childrens-mental-health-and-wellbeing-strategy

Kerns, S. E., Pullmann, M. D., Putnam, B., Buher, A., Holland, S., Berliner, L., Silverman, E., Payton, L., Fourre, L., Shogren, D., & Trupin, E. W. (2014). Child welfare and mental health: Facilitators of and barriers to connecting children and youths in out-of-home care with effective mental health treatment. Children and Youth Services Review, 46, 315–324. DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.09.013

Leckning, B., He, V. Y., Condon, J. R., Hirvonen, T., Milroy, M., & Guthridge, S. (2021). Patterns of child protection service involvement by Aboriginal children associated with a higher risk of self-harm in adolescence: A retrospective population cohort study using linked administrative data. Child Abuse & Neglect, 113, 104931. DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.104931 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33461112

Mathews, B., Pacella, R. E., Scott, J. G., Finkelhor, D., Meinck, F., Higgins, D. J., Erskine, H. E., Thomas, H. J., Lawrence, D., Haslam, D. M., Malacova, E., & Dunne, M. P. (2023). The prevalence of child maltreatment in Australia: Findings from a national survey. The Medical Journal Australia, 218(Suppl. 6), S13–S18. DOI https://doi.org/10.5694/mja2.51873 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37004184

McLean, K., Hiscock, H., Scott, D., & Goldfeld, S. (2021). Foster and kinship carer survey: Accessing health services for children in out-of-home care. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 57(1), 132–139. DOI https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.15157 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32949433

Mendes, P., & Chaffey, E. (2024). Examining the mental health care needs and outcomes of young people transitioning from out-of-home care (OOHC) in Australia. Institutionalised Children Explorations and Beyond, 11(1), 103–124. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/23493003231182474

Mendes, P., Johnson, G., & Moslehuddin, B. (2011). Young people leaving state out-of-home care: Australian policy and practice. Melbourne: Australian Scholarly Publishing.

National Mental Health Commission. (2021). National Children’s Mental Health and Wellbeing Strategy. Canberra: Australian Government. mentalhealthcommission.gov.au https://www.mentalhealthcommission.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-03/national-children-s-mental-health-and-wellbeing-strategy---full-report.pdf

Osborn, A., & Bromfield, L. M. (2007). Outcomes for children and young people in care. Research Brief No. 3. Melbourne: National Child Protection Clearinghouse, Australian Institute of Family Studies. citeseerx.ist.psu.edu https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=fad87a1a7aed6da303073e712a146fc1c54b5bf1

Policy Writing Group. (2020). Fit for purpose: Improving mental health services for young people living in rural and remote Australia. Melbourne: Orygen. orygen.org.au https://www.orygen.org.au/Orygen-Institute/Policy-Areas/Government-policy-service-delivery-and-workforce/Service-delivery/Fit-for-purpose-Improving-mental-health-services-f/Orygen_Fit-for-Purpose?ext=

Royal Australasian College of Physicians. (2023). Health care of children in care and protection services: Australia position statement. Sydney: RACP. racp.edu.au https://www.racp.edu.au/docs/default-source/advocacy-library/health-care-of-children-in-care-and-protection-services-australia-position-statement.pdf

Russell, D. H., Trew, S., & Higgins, D. J. (2021). Vulnerable yet forgotten? A systematic review identifying the lack of evidence for effective suicide interventions for young people in contact with child protection systems. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 91(5), 647–659. DOI https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000555 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34383517

Appendix I

Audit 1

Appendix II

Audit 2