Article type: Review

30 June 2025

Volume 47 Issue 1

HISTORY

RECEIVED: 17 March 2025

REVISED: 21 May 2025

ACCEPTED: 22 May 2025

Article type: Review

30 June 2025

Volume 47 Issue 1

HISTORY

RECEIVED: 17 March 2025

REVISED: 21 May 2025

ACCEPTED: 22 May 2025

![]() A scoping review of the transition experiences and outcomes of young women leaving residential out-of-home care

A scoping review of the transition experiences and outcomes of young women leaving residential out-of-home care

Affiliations

1 Department of Social Work, Monash University, Melbourne, Vic., Australia

Correspondence

*Mrs Yujie Zhao

Contributions

Yujie Zhao - Study conception and design, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting of manuscript

Jacinta Waugh - Study conception and design, Critical revision

Philip Mendes - Study conception and design, Critical revision

Yujie Zhao1 *

Jacinta Waugh1

Philip Mendes1

Affiliations

1 Department of Social Work, Monash University, Melbourne, Vic., Australia

Correspondence

*Mrs Yujie Zhao

CITATION: Zhao, Y., Waugh, J., & Mendes, P. (2025). A scoping review of the transition experiences and outcomes of young women leaving residential out-of-home care. Children Australia, 47(1), 3057. doi.org/10.61605/cha_3057

© 2025 Zhao, Y., Waugh, J., & Mendes, P. This work is licensed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence

Abstract

Young people transitioning from out-of-home care (OOHC) are widely recognised as a vulnerable group, and the subset of those who have been placed in residential care experience the greatest challenges after leaving care. Young women exiting from residential care face numerous additional gender-specific challenges, such as early pregnancy and gender-based abuse, yet they have rarely been the subject of specific research. This study aims to examine the discrete leaving-care transitions experienced by young women exiting residential care settings globally.

A scoping review was conducted in a global context, involving 31 peer-reviewed articles from both Global North and Global South countries. By analysing the key findings of these selected studies, this review identified a large range of topics related to female residential care leavers, including their experiences and outcomes before, during and after the transition from care. While the experiences of these young women vary in different contexts, they still exhibit many similar patterns. However, in research conducted particularly in Global North countries, this group is often only a small subset of broader study populations rather than the primary focus. Consequently, the findings related to them remain limited, underscoring the need for greater attention and dedicated investigation.

Keywords:

care leaver, female, gender difference, residential care, young people transitioning from care.

Introduction

In general, young people transitioning from out-of-home care (OOHC) are considered vulnerable during and after their transitions to independent living (Mendes, 2023; Mendes et al., 2014; Mendes & McCurdy, 2020). Many studies show that residential care leavers are likely to have the poorest leaving-care outcomes in many domains compared with their counterparts from forms of home-based care such as kinship and foster care, including independent skills, education and employment, emotional wellbeing, housing, social reintegration and engagement with the criminal justice system (Lau & Hopkins, 2023; Mendes et al., 2022; Mendes & McCurdy, 2020; Sacker et al., 2021; Sauerwein & Graßhoff, 2025). Although residential care is often considered to be the last resort when placing children in OOHC (Mendes et al., 2022), as of June 2022 in Australia, 8.5% of 45,400 children in care are still living in residential care (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), 2024a). The young people placed in residential care are usually older adolescents who have experienced high placement mobility and may present with various behavioural challenges (AIHW, 2022; Narey, 2016; Department of Families, Fairness and Housing (DFFH), 2018). In Victoria, for example, it has been estimated that older young people exiting residential care make up between 20 and 25% of the overall care leaver cohort (Victorian Government, 2022).

Residential care in a global context

Without a globally standardised definition, residential care is subject to regional variation, with its scope shaped by differing cultural, social and regulatory contexts (Desmond et al., 2020). In the United Nations Guidelines for the Alternative Care of Children, residential care is defined in contrast to family-based care, and is characterised as a group setting that may serve as a short-term or long-term arrangement that is aimed at ensuring the safety and wellbeing of children (UN, 2010). According to the AIHW (2025), residential care in Australia refers to accommodation provided to children and young people who are mostly on child protection orders and unable to reside with biological parents. Echoing the UN Guidelines (2010), it is emphasised that, contrasting with foster and kinship care, children and young people in residential care are cared for by rostered staff rather than home carers or extended family members (AIHW, 2025; Department of Social Services (DSS), 2011).

In the USA, residential care encompasses a wide definition, including, for example, children and young people in the child welfare system, involved in juvenile crime, disengaged from education providers, diagnosed with mental health problems or self-referred by parents to private placement (Lee & Bellonci, 2022). Similarly, residential care in the UK encompasses different types of placements, including residential care institutions, boarding schools, restricted-access care units, non-regulated residential care facilities and hostels (Narey, 2016). In some countries in the Global South, which are often considered less economically and politically affluent, residential care can include orphanages and providing care for children who have lost their parents to poverty or disease such as HIV/AIDs. The possibility of transition into extended family networks is frequently hindered by the financial constraints or unavailability of relatives (Roche, 2019). Although the terminology and operational models of residential care vary across different regions, in the present article, the term residential care is used to refer to all individuals living in government care within group facilities and being cared for by non-parental caregivers (AIHW, 2025; DSS, 2011).

Most countries in the Global North, which is typically associated with greater economic prosperity, prioritise kinship and foster care over residential care, and place a relatively smaller proportion of children in care into residential care. The proportion of residential care among all types of placements varies across countries (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), 2022). In New Zealand, Ireland, Norway, Australia, the United States and Latvia, residential care accounts for a relatively low percentage of care arrangements, typically less than 10%. Israel has the highest proportion of children and young people in residential care among 18 OECD countries, making up approximately two-thirds of all placements (OECD, 2022). In contrast, residential care, or institutional care (as is more commonly used in Global South countries), is playing an increasingly common role in Global South countries. For example, in Zimbabwe, the growth in the population of children entering OOHC has been outpaced by a more rapid increase in the number of residential care facilities available during 2004–2014 (UNICEF, 2023).

According to an estimate by UNICEF (2024), an average of 102 per 100,000 children are living in residential care globally. When considering the total number of residential care residents, Desmond et al. (2020) conducted a broad-ranging global research project that included data from 136 countries. That study estimated the range in number of children and young people in residential care in 2015 to be between 3.18 and 9.42 million. Asia accounts for the largest population of children residing in residential care at 1.13 million, followed by Europe and central Asia, Asia and Pacific, sub-Saharan Africa, Middle East and North Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, and, the lowest, North America at 0.09 million (Desmond et al., 2020). The outcomes and experiences of individuals leaving residential care have been widely criticised within academic discourse. In response, many countries, particularly in the Global North, have implemented measures in favour of deinstitutionalisation and to restrict their reliance on residential care (Desmond et al., 2020; OECD, 2022; Roche, 2019). In contrast, within Global South countries, residential care plays a substantial and even dominant role in providing care and accommodation for vulnerable children (Faith to Action Initiative, 2016; Mishra, 2024; Roche, 2019).

In Australia, there have been recent practice and policy reforms to improve the quality of care-leavers’ outcomes. All eight jurisdictions have introduced extended-care policies in response to the Home Stretch advocacy campaign that recommends forms of mandatory support until the age 21 (Home Stretch, 2025). However, in a number of states, extended care support is only available to young people who have specifically transitioned from home-based care and sadly, residential care leavers have not been fully included in the scope of post-18 years assistance, particularly in housing (Mendes et al., 2023; Zhao & Waugh, 2025).

Gender differences in leaving care

Many studies have argued that the pre- and in-care experience is different between young people of different genders (Royal Commission into Abuse in Care, 2024), which may lead to disparate pathways and outcomes after leaving care. According to the well-known Midwest Study, a longitudinal study of outcomes comparing recipients and non-recipients of extended care programs, conducted by Courtney et al. (2007) in the USA, notable gender differences were found in various domains, including employment, education, hospitalisation, acceptance of government welfare benefits, substance misuse, sexual behaviours and pregnancy, intimate relationships and marriage, parenthood, engagement with the criminal justice system, victimisation of physical and sexual violence, and reintegration. Echoing the Midwest study, some research studies have suggested that female care leavers exiting all types of placements may also experience discrete post-care challenges, including financial difficulties, single parenting, dependence on coercive relationships, cultural/traditional family roles and histories of abuse, including sexual abuse (Bond, 2017; Gypen et al., 2023; Hlungwani & van Breda, 2020; van Breda & Hlungwani, 2019).

Gender-based violence and early pregnancy

Due to marked differences between men and women in terms of biology, social roles and emotional wellbeing, their experiences, needs and levels of risk in gender-based violence tend to vary significantly (Baynes-Dunning & Worthington, 2013). These differences influence the type of treatment they receive, their vulnerability to various forms of violence, and the nature of the support they require. To be more specific, girls are reported to be more likely to experience child maltreatment than boys at a younger age (51.2% and 48.5% respectively; US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau, 2011). This pattern continues into adolescence. Juvenile victims of violent crimes are more likely to be female, and young women are three times more likely to become victims of sexual assault (Baynes-Dunning & Worthington, 2013). Evidence consistently shows that women disproportionately represent the primary victims in family and domestic violence (80% of primary victims are women in adulthood), and this proportion is consistent with that reported among care leavers (AIHW, 2024b). Similarly, another Australian study involving only female participants also reveals a heightened likelihood of young mothers with in-care experiences becoming victims of family violence (Barker et al., 2022).

Early parenthood emerges as another integral and unavoidable topic when examining the experiences and challenges faced particularly by female care leavers. In both the global and Australian context, young women exiting OOHC have a much higher chance of early pregnancy compared with their counterparts in the general population (Gill & Luu, 2025; Muir et al., 2019). In New South Wales (NSW), young women aged 15–19 years with OOHC experience are three times more likely to become early mothers than their non-care-experienced peers (Gill & Luu, 2025). When narrowing down to the different outcomes between young women in different placement types, residential care is associated with early pregnancy and parenting due to a number of discrete factors, including negative peer influence, substance misuse, sexual abuse, disengagement from school (which can result in a lack of, or diminished sexual education), and young people’s reluctance to engage in sex-related discussions with rostered staff due to a lack of trust or rapport (Purtell et al., 2021, 2022). Similarly, Fairhurst et al. (2016) and Farber (2014) attributed the causes of early pregnancy among female care leavers to factors such as traumatic pre- and in-care experiences, individual characteristics, social isolation, poverty, dropping out of school, unemployment, challenging behaviours, inappropriate relationships, peer pressure, risky sexual activities, lack of guidance and support regarding safe and healthy sex and intimate relationships. These factors, to a great extent, correspond with the topics most frequently discussed in selected scholarly articles, which will be examined later in our findings.

Research aim

Although there has been some academic attention on female care leavers internationally, scholarly research and data on female care leavers in Australia are limited, especially when it comes to those who have transitioned out of residential care. The most relevant Australian academic journal article examines residential care leavers’ experiences and outcomes and the fundamental needs related to extended care support for this particular group (Mendes et al., 2022). However, the unique challenges faced by women and possible gender differences are not covered in this article.

Due to the limited support provided by Australia’s extended care policies for residential care leavers (Zhao & Waugh, 2025), particularly in terms of services catering to the specific needs of women, our article aims to explore the experiences and needs of female care leavers exiting residential care settings, with the goal of offering more suitable support tailored to their needs.

Methods

Searching process

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the current state of academic research on female residential care leavers, a scoping review was considered an effective method. Following the scoping review protocol (Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI), 2024a), a research question was developed to initiate the review process – what does the existing global literature tell us about the transition experiences and outcomes of young women leaving residential out-of-home care? The next step was finalising the elements outlined by the PCC mnemonic, which stands for Population, Concept, and Context (JBI, 2024b). The PCC map further helped the construction of the strategy plan, including searching terms showed in Table 1.

Prior to the formal literature search, gold-set articles, those prominent and widely cited articles that were highly relevant to the research topic, were selected (Lamb, 2023). An initial search was conducted to locate gold-set articles that were utilised later to determine the most relevant databases (Lamb, 2023). These gold-set articles also helped to identify keywords and concepts to be included in the searching map and strategy (Monash University, 2025). Eight gold-set articles were identified, and their presence in various databases was tested to finalise the selection of databases for the second search process (JBI, 2024c; Lamb, 2023). As a result, four scholarly databases were chosen (Table 1). Given the scarcity of studies on female residential care leavers, ‘female’ was not included as one of the concepts in the initial broad search. Instead, the authors sought to identify any insights or traces related to women or gender differences within the broader body of research on residential care leavers. The search was limited to articles published from 2014 to 2024 to ensure their relevance to current policies and practices.

Table 1. Search strategies in four databases, PsycInfo, Scopus, ProQuest and Taylor & Francis

| Search terms | PsycInfo | Scopus | ProQuest | Taylor & Francis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaving care/care leaver (Population) |

(leaving care or care leaver* or transitioning from care or transition* from OOHC or transition into adulthood or Youth transition*).mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh word] ("leaving care" or "care leaver*" or "transition* from care" or "transition* from OOHC" or "transition* into adulthood" or "youth transition*").mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh word] |

"leaving care" OR "care leaver*" OR "transition* from care" OR "transition* from OOHC" OR "transition* into adulthood" OR "youth transition*" | "leaving care" OR "care leaver*" OR "transition* from care" OR "transition* from OOHC" OR "transition* into adulthood" OR "youth transition*" | "leaving care" OR "care leaver*" OR "transition* from care" OR "transition* from OOHC" OR "transition* into adulthood" OR "youth transition*" |

| Outcome/life change (Concept) | (Experience or outcome* or challenge* or perspective* or view* or lived experience or life course).mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh word] | "experience" OR "outcome*" OR "challenge*" OR "perspective*" OR "view*" OR "lived experience" OR "life course" | "experience" OR "outcome*" OR "challenge*" OR "perspective*" OR "view*" OR "lived experience" OR "life course" | "experience" OR "outcome*" OR "challenge*" OR "perspective*" OR "view*" OR "lived experience" OR "life course" |

| Residential care (Context) |

(Residential Care or institutional care or resi-care or Child*"s home or child*"s house*).mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh word] ("residential care" or "institutional care" or "rest-care" or "child*"s home" or "child*’s house*").mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh word] |

"residential care" OR "institutional care" OR "rest-care" OR "child*"s home" OR "child*"s house*" | "residential care" OR "institutional care" OR "rest-care" OR "child*"s home" OR "child*"s house*" | "residential care" OR "institutional care" OR "rest-care" OR "child*"s home" OR "child*"s house*" |

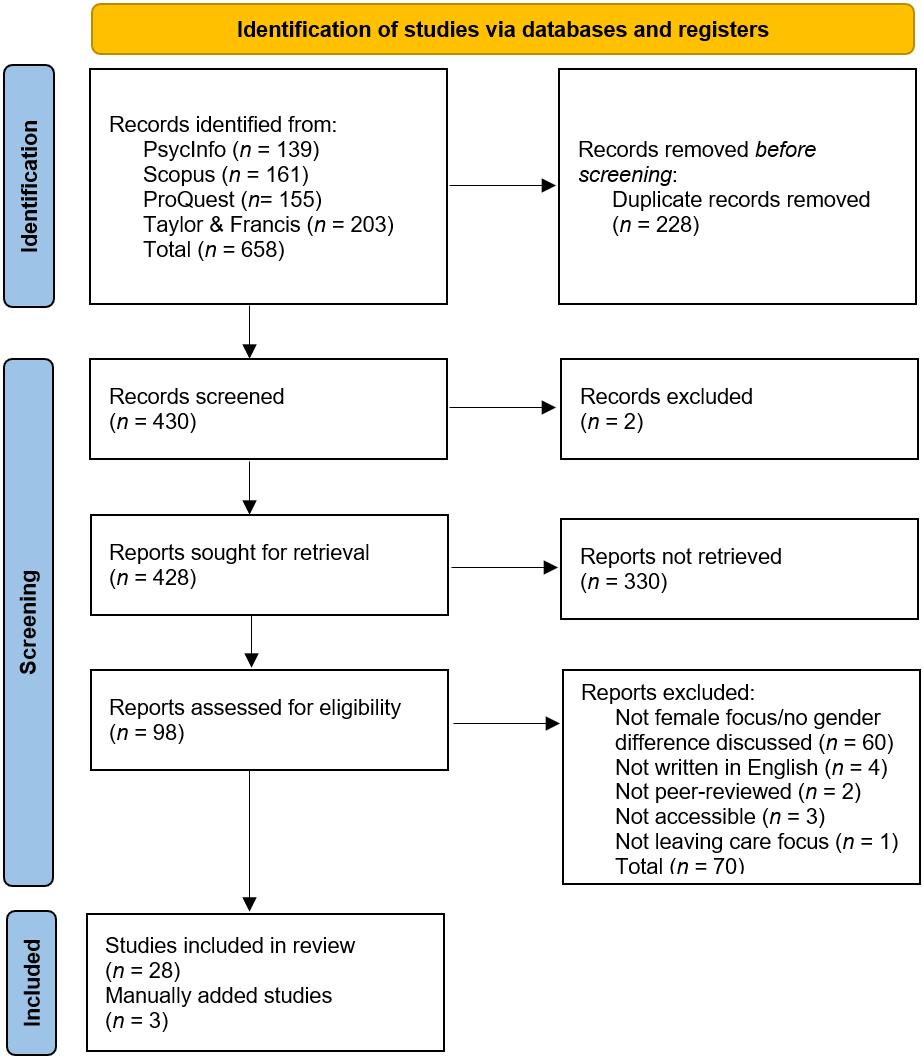

There were two stages in the article screening process – title and abstract examination and full-text examination (JBI, 2024d). During the first stage of inclusion, the criteria centred on identifying studies that explored leaving-care issues within residential care settings. In the second stage, articles were assessed as to whether they included content related to females, women or gender difference. Ninety-eight studies were included during the first screening stage and 28 articles met the criteria for inclusion in the second stage. Two Australian articles, which were not focused on residential care, and therefore did not appear in the preliminary search results, met the second-stage screening criterion and were manually incorporated. Another article published in late 2024 was manually added to the review, given that the search process had been completed by late–mid-2024 (see PRISMA flow diagram, Figure 1}). To ensure the rigours of the screening process, two reviewers were involved in the first stage. The first author served as the lead reviewer in the second stage, with continuous input and collaborative discussions with the other authors to ensure consensus on specific inclusion and exclusion decisions. Data retrieved from all databases in the first screening stage were systematically recorded in Excel and Word documents to facilitate sharing and distribution. In the second stage, the information was stored in EndNote for better organisation and citation management.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram

Included papers

In total, 31 peer-reviewed scholarly articles were included in this study for data analysis. Sixteen articles were conducted in Global South countries and the remaining 15 were from Global North countries. The prevalence of residential care in the Global South may explain why studies from these regions tended to focus more explicitly on young women leaving residential care settings. Conversely, in the Global North, findings related to young women leaving residential care often constituted only a minor aspect of broader research outcomes, rather than being the central focus. By including articles from both the Global South and the Global North, it was hoped that a relatively comprehensive understanding of young women exiting residential care in different social, cultural, economic and political contexts could be achieved.

A data charting table was developed during the data extraction process (JBI, 2024e). As shown in Appendix I, this scoping review included one narrative review and 30 primary research studies, covering approximately 3663 female and 2782 male participants aged between 12 and 85 (the exact number may not be entirely accurate because some selected articles only reported the proportion of women among their participants rather than specific numbers) as well as 44 stakeholders such as carers, government staff, service providers and non-government organisation (NGO) workers. In terms of the aims of the 31 studies, they examined different stages of the leaving-care process. Eight articles explored preparation for the transition, 15 focused on the transition itself, and 27 discussed post-transition outcomes and retrospective experiences (several articles addressed more than one stage). Among the 30 primary research studies, eight of them employed quantitative data only, and the remaining 22 employed raw data collected through mostly qualitative and mixed methodologies, including in-depth interviews with different levels of interview structuring, focus groups, site observation, pre–post surveys and questionnaires (Appendix I). Ethically, as a scoping review focusing on a particularly marginalised group, the ethics approval of each selected article was taken into account during the screening stage. All articles screened in this study implemented proper and appropriate ethical consideration processes within their research studies.

Results

The appropriate methodology for scoping reviews in data extraction and analysis is controversial in academia (Pollock et al., 2023). According to JBI (2024f) guidelines, basic concept frequency count works for most scoping reviews and content analysis can be employed for in-depth analysis based on authors’ decisions, whereas thematic analysis, which is widely used in analysing qualitative data, is more suited to systematic review (JBI, 2024f). Similarly, Pollock et al. (2023) considered that content analysis could be efficient for a scoping review as long as the subject includes examining experiences of a social issue. Considering the characteristics of selected articles in the present study, and being a scoping review, content analysis was selected for the data analysis for both qualitative and quantitative data in this study (JBI, 2024f). All 31 articles were transferred from EndNote to NVivo for coding and data analysis.

Since the articles were not narrowed down by content scope during the selection process and were instead chosen solely based on the identity of the subjects (female residential care leavers) under study, the selected articles covered a wide range of topics, leading to a larger number of codes. In total, 22 main codes and 37 sub-codes were identified in the coding process, and these codes underwent a secondary classification and summary to condense the key findings of this scoping review. Three main codes (Before the transition, During the transition and After the transition) were finally arranged in chronological order, with 14 sub-codes encapsulating challenges and feelings experienced by young women leaving residential care in various domains throughout the whole leaving-care transition.

Before the transition

Childhood before entering care

Many studies stated that young girls had experienced a traumatic childhood before entering care (Coler, 2018; Dutta, 2018; Pasli & Aslantürk, 2024; Whitelaw, 2023). In these articles, female participants were more likely than male participants to have experienced maltreatment, neglect, multiple forms of abuse (including emotional, physical and sexual), various types of violence and poor parental capabilities (such as drug and alcohol misuse) before entering care, and these were largely considered as the reasons for their removal (Lanctôt, 2020; Pasli & Aslantürk, 2024; Prévost-Lemire et al., 2024; Whitelaw, 2023). In contrast, instead of abuse, the absence of parents was more common for male participants entering care (Pasli & Aslantürk, 2024).

Differing from the aforementioned, Indian research studies have reported that over half of young girls in residential care in India were placed there by their parents or relatives, rather than enforcement agencies, and the major reasons for them being taken into care were related to non-intact family structure, including the loss of both parents or a single parent, or parental divorce (Dutta, 2017a, 2017b, 2018). In some of India’s neighbouring countries in the Global South, female children or young people had suffered poverty, unmet educational needs, sexual exploitation, sexual assault by familial members and/or diseases such as HIV/AIDs before entering care (Dutta, 2018).

The traumatic childhoods these young girls had experienced with their biological families led to not only risky behaviours such as absconding (Dutta, 2018), but also had a profound impact on their development and future lives. Lanctôt (2020) found that the difficulties that young girls faced in childhood correlated with their level of social disconnection in adulthood. The absence of parental love and recognition remained a deep-seated emotional wound, impairing their capacity for healthy social interactions (Gabriel et al., 2021).

In-care experience

Female care leavers presented complex attitudes towards their journeys in residential care. Perceived Contribution of Residential Care (PCRC) was utilised as a measure in assessing care leavers’ satisfaction with their in-care experience in an Israel study. Compared with male care leavers, female care leavers were reported with higher Perceived PCRC, which indicated that young girls were more likely to have a positive experience in residential care than boys (Sulimani-Aiden et al., 2024). The research team attributed the gender disparity to sexism in the community and the different ways girls and boys are treated in residential care (Sulimani-Aiden et al., 2024). Similarly, a significant proportion of Indian female residential care leavers were satisfied with the service and support they received in care; only 3% reported strong dissatisfaction and 4% indicated mild dissatisfaction (Dutta, 2018).

Conversely, in a study conducted in Zimbabwe, despite the basic support, young women did not give a lot of credit to their experience in institutional care. Young women being placed in government-funded institutional care in this study were reportedly more likely to have complaints about their overall experience, particularly in relation to the disparities between themselves and their peers with no in-care history; for example, a lack of pocket money, no birthday parties, and the limited trust and autonomy granted by caregivers (Berejena Mhongera & Lombard, 2017). A Switzerland study that focused on former care leavers who were in residential care in 1950–1990 also indicated poor in-care experiences among their participants (Gabriel et al., 2021). Upon reflecting on their past experiences, the most immediate and vivid memories were those of feeling powerless, alongside the experiences of abuse and neglect within the residential care settings (Gabriel et al., 2021). Not surprisingly, all their experience in residential care would have substantial influence on their self-growth and leaving-care outcomes (Sulimani-Aiden et al., 2024).

The care leavers’ dissatisfaction was evident, yet the caregivers appeared to face the situation with a sense of inevitability and helplessness (Van Breda et al., 2022). An Ethiopia study gave voice to those caregivers preparing girls/young women to transition to independence. The caregivers in this study firmly believed that a moderate form of authoritative parenting style could promote greater autonomy and independence. However, young women under their care often disregarded their guidance and were instead influenced by peers or older care leavers to engage in behaviours deemed undesirable (Van Breda et al., 2022). Apart from the challenges in parenting practices, these caregivers also pointed out the lack of material support available to the young people in residential care (Van Breda et al., 2022).

During the transition

Reasons for leaving care

Many young women were unable to have a clear understanding of the transition and pathways after leaving care (Dutta, 2017a). In addition to legal/policy reasons, such as the termination of child protection orders, there were other factors that led to the sudden or premature departure from OOHC among female children and young people in residential care, particularly in some low-income regions. A significant proportion of young women in India left care for family reunion, arranged marriages, career development, or as a result of punitive actions by the facility due to misconduct behaviours (Dutta, 2017a). Frimpong-Manso et al. (2022) also indicated that young mothers in Ghana and Uganda were forced to leave residential care due to pregnancy, which resulted in additional challenges and difficulties during the transition.

Preparing for the transition

The preparation for care leavers’ transitions to independent living was frequently subject to criticism. Many research studies found that young women often left care unprepared for independent living and financial management and with inadequate educational level and cultural awareness for social integration (Pryce et al., 2016; Van Breda et al., 2022). According to a South African study, young girls were not allowed to do house chores, including cooking, to reduce the risk of potentially breaking child-labour laws, which resulted in their disengagement in becoming independent (Van Breda et al., 2022). Similarly, participants from Zimbabwe reported that they were neither trained nor provided relevant knowledge in independent living skills (Berejena Mhongera & Lombard, 2016). Many participants complained about the abrupt termination of their in-care lives and the incomplete leaving-care system, including sudden evictions due to early pregnancy and supposed misbehaviours, which led to inadequate time in preparing (Dutta, 2017a; Frimpong-Manso et al., 2022). On the contrary, approximately two-thirds of female care leavers in an Indian study believed that they were fully equipped with the basic survival skills to handle upcoming independent living (Dutta, 2018).

Dutta (2017a) summarised that good transition planning in India was associated with a higher age of leaving care, stable in-care experience, relationships with residential care workers and peers, connection with original families and communities, local policies and the level of young people’s engagement. Sadly, there was a notable absence of young women’s inclusive participation in the decision-making process, with many individuals experiencing paternalistic decision making in which choices were imposed upon them rather than being collaboratively determined (Berejena Mhongera & Lombard, 2017; Dutta, 2017a, 2018; Purtell et al., 2021). This may be due to caregivers’ perceptions of controlled authoritative parenting being helpful in building independence among young women in residential care (Dutta, 2017a). Conversely, some caregivers perceived the young women’s unpreparedness as their own fault, arguing that they had provided sufficient guidance, but the girls did not heed their advice (Van Breda et al., 2022).

Apart from basic independent living skills and decision-making skills, some participants additionally required training and opportunities to develop their social skills (Berejena Mhongera & Lombard, 2016). Social and networking skills could play a vital role in many domains, such as community integration, traditional customs, cultural etiquette and social graces (Van Breda et al., 2022; Van Breda & Hlungwani, 2019). All in all, adequate attention, customised support, trust-based relationships with caregivers and/or staff, and extended care could better prepare young women during the transition phrase (Berejena Mhongera & Lombard, 2017; Dutta, 2018).

After the transition

Attitudes towards the general post-care support

A general concern and challenge for young women leaving residential care was inadequate post-care support (Van Breda et al., 2022). In many cases, many female care leavers might not be eligible for post-care support due to limited resources, top-down decisions, distance barriers, a fragmented service delivery framework and lack of gender-specific services (Berejena Mhongera & Lombard, 2017; Dutta, 2017a; Gwenzi, 2023a). Individually, it was also evident that the more traumatic the childhood, the stronger the likelihood of greater isolation and disconnection after leaving care, and the more likely care leavers were to reject post-care support services they were entitled to access (Lanctôt, 2020). While a considerable amount of criticism was voiced, a few participants in these studies still shared positive comments on post-care support. Post-care support offered more benefits than drawbacks for some particular groups of women, including orphans, individuals who had lost contact with birth families and those with strong bonds with staff members (Dutta, 2017a).

Definition of success

When defining a successful transition, individuals might hold varying interpretations; for example, being independent and self-reliant, having stable post-care support, access to adequate financial assets and supplies, secure housing, good health, staying away from violence and crime, avoiding drug abuse, achieving educational qualifications and maintaining steady employment, to name a few (Berejena Mhongera, 2017). Beyond these perspectives, many studies in Global South countries found that relationship-based achievements are particularly significant for female care leavers, such as marriage, intimate relationships, relationships with original families, relationships with their own children and social integration (Berejena Mhongera, 2017; Dutta, 2017b; Gabriel et al., 2021; Gwenzi, 2023b; Van Breda & Hlungwani, 2019).

Education

Although residential care leavers were reported to have lower educational achievements compared with foster care leavers and the general population (Gypen et al., 2022), the majority of female participants valued the importance of education and aimed to complete a certain number of degrees or qualifications before and after leaving care (Berejena Mhongera & Lombard, 2017; Sulimani-Aiden, 2020). Indeed, female students often outperformed their male counterparts, with higher levels of academic engagement (Cassarino-Perez et al., 2019). Some governments, like that of Scotland, also supported those who intended to pursue higher degrees, and care leavers there were entitled to a large range of financial support grants if they undertook academic studies (Whitelaw, 2023). Unsurprisingly, good education conferred significant advantages to these young people. Researchers found that the higher level of education they achieved, the smoother their job hunting and social reintegration would be (Dutta, 2018; Gypen et al., 2022;).

However, not all participants were allowed to pursue educational achievements due to various barriers. For example, in some cultural and societal contexts, some young girls were encouraged, or even pushed, to prioritise marriage and financial dependence on men over pursuing personal development and completing higher degrees (Sulimani-Aiden, 2020). Poverty was emphasised in low-income regions as another holdback. Due to lack of financial support for secondary and post-secondary education in Zimbabwe, only those attracting private sponsorship or government funding were allowed to continue their academic learning (Berejena Mhongera, 2017). Similarly, many Indian female participants dropped out of school because of financial constraints, therefore impeding their competitiveness in finding well-paid jobs (Dutta, 2017a). Apart from the impact on employment, dropping out of school also, to some extent, affected women’s decision making for early pregnancy (Purtell et al., 2021). Even among young women with access to education, there were other reasons for dropping out of school, such as peer discrimination and emotional and behavioural problems (Berejena Mhongera & Lombard, 2017; Gypen et al., 2022).

Employment and finance

Young women exiting residential care were reported to have difficulties in securing a job after leaving care (Van Breda et al., 2022), and the gap between them and their peers who had exited from other types of placements or with no care experience became increasingly obvious over time (Gypen et al., 2023). Those who were not able to have steady employment, were reported to have no shelter and engage in under-the-table jobs such as begging and sex work (Pryce et al., 2016). Compared with male care leavers, female care leavers were less likely to engage in employment due to traditional family roles and involvement in early parenting (Frimpong-Manso et al., 2022; Kääriälä et al., 2019). This issue was particularly pronounced among residential care leavers, because they were at greater risk of being constrained by early parenthood (Kääriälä et al., 2019; Purtell et al., 2021). Similarly, Gypen et al. (2022) found two variables that closely associated with care leavers’ income after leaving care: educational attainment and gender. The income of young women leaving care tended to be disproportionately low compared with that of males in Belgium, both in terms of wages and supplementary benefits when they were unemployed (Gypen et al., 2023). Participants in Zimbabwe attribute their low levels of employment to structural factors, such as institutional inaction, which excluded them from employment opportunities and resources (Berejena Mhongera & Lombard, 2016).

The low employment and wage rate inevitably resulted in financial hardship for many female care leavers (Dutta, 2017a; Sulimani-Aiden, 2020). Many female participants expressed their need for financial support, which was either not provided at all or poorly provided in low-income countries such as Zimbabwe (Berejena Mhongera & Lombard, 2016). For those care leavers in countries with more comprehensive welfare support, such as Australia, they were entitled to federal support like Centrelink parenting payments, but the accessibility remained controversial (Purtell et al., 2022). Caregivers who prepared girls to leave care additionally mentioned that many girls lack financial capability and maturity in managing their money (Van Breda et al., 2022). As a consequence, young women transitioning from residential care were highly likely to suffer financial insecurity, which may force them to live in precarious and dangerous conditions, such as violent households, unequal intimate relationships, unsafe sex, sexual exploitation and gender-based crime (Berejena Mhongera & Lombard, 2016; Berejena Mhongera, 2017).

Sexual abuse and exploitation

Women seemed inherently more likely to be targeted and subjected to sexual abuse due to systemic gender inequalities and societal power dynamics. For example, female participants in several studies talked about sexual maltreatment by their fathers or male relatives, such as brothers, in households where they seek refuge before entering care, which acted as an explanation of why they preferred independent living rather than returning back home after leaving residential care (Sulimani-Aiden, 2020). Even after they were placed in residential care, comprehensive sex education was often lacking, particularly in culturally conservative societies, where basic knowledge about sexuality, reproductive health and healthy relationships was treated as taboo (Gabriel et al., 2021). As a result, female care leavers were reported to stay in situations with higher risk of sexual abuse and exploitation during and after their transitions to emerging adulthood (Berejena Mhongera & Lombard, 2017; Pryce et al., 2016).

Isolation and discrimination

Isolation and loneliness appeared to be widespread among young women leaving residential care. An absence of dependable allies, a beleaguered family of origin, a maltreated childhood, inaccessible support services and financially strained social pursuits were reported as the main contributing factors (Berejena Mhongera & Lombard, 2016; Berejena Mhongera & Lombard, 2017; Dutta, 2017a, 2017b; Gabriel et al., 2021; Hlungwani & van Breda, 2020; Lanctôt, 2020; Sulimani-Aiden, 2020). Additionally, some participants also mentioned discrimination stemming from stereotypes, which led them to be perceived as problematic or bad kids and therefore ostracised (Berejena Mhongera, 2017; Pryce et al., 2016; Whitelaw, 2024). Nevertheless, female care leavers were reported to be less engaged with criminal activities than males, and the crime rate among female participants was even 0% in a South Africa study (Van Breda, 2020). Despite experiencing passive isolation (involuntary exclusion or social isolation), some young women in Australia purposely keep away from support services because of their dissatisfaction with the welfare system (Purtell et al. (2021, 2022).

Young mothers further described their feelings of disconnection and rejection across relationships with families, partners, fathers of their children and friends (Coler, 2018; Parry et al., 2023; Prévost-Lemire et al., 2024). Although these mothers attempted to seek help, they often found no one to rely upon (Prévost-Lemire et al., 2024). Therefore, they had no choice but to take on all the responsibilities of caring for their children by themselves, sometimes losing their sense of self (Lanctôt & Turcotte, 2018; Prévost-Lemire et al., 2024). Some mothers took initiatives to cut off connections with people they believed to be threatening, including children’s fathers perceived irresponsible, dysfunctional families perceived to have caused their trauma and support services they saw as exposing their children to child removal (Lanctôt & Turcotte, 2018; Prévost-Lemire et al., 2024). These self-defensive techniques exacerbated the loneliness and disconnection of young women and blocked potential helpers and support (Prévost-Lemire et al., 2024).

Relationships and reintegration

Many female care leavers recounted the pain they endured in various relationships; for example, being violently abused by intimate partners, child maltreatment perpetrated by their parents or other family members, betrayals in friendships and discord with their own children (Prévost-Lemire et al., 2024). However, they still placed great importance on, and actively strived to build, positive relationships during and after leaving care; for example, rapport with staff from formal support services, peer support, closer bonds with trusted family members and colleagues from workplaces, connections with local communities and healthy romantic relationships (Berejena Mhongera, 2017; Dutta, 2017a; Gwenzi, 2023a; Lanctôt, 2020; Parry et al., 2023; Prévost-Lemire et al., 2024; Van Breda & Hlungwani, 2019). People with whom these women had strong relationships often acted as helpful networks and provided support in many ways, for instance, seeking employment (Dutta, 2017b).

Coll et al. (2022) stated that, regardless of gender, participants who exhibited positive improvement following their departure from therapeutic residential care in the USA had slightly higher interpersonal and family scores than the counterparts in their study, while Van Breda and Hlungwani (2019) found that women tended to place greater emphasis on intimate relationships and parent–child relationships than men. Romantic relationships were often regarded as one of the avenues to escape the confines of the original family, and some women had consequently found support and affection from their partners and partners’ families (Berejena Mhongera & Lombard, 2016). Young mothers also reported their strong reliance on romantic relationships whether or not with the father of their children (Prévost-Lemire et al., 2024). However, apart from love and support, romantic relationships might also bring fights, arguments and even violence, and the experience of female care leavers further placed them at a disadvantage within the context of marriage and romantic relationships (Dutta, 2017b; Van Breda & Hlungwani, 2019). In an even worse scenario, some pregnant participants experienced intimate violence committed by the fathers of their unborn child when they disclosed their refusal to undertake an abortion, and also serious suicidal thoughts during pregnancy (Frimpong-Manso et al., 2022).

Females transitioning from residential care maintained varying degrees of connection with their families of origin, and this proportion reached 74% in an Indian study (Dutta, 2017b). However, returning to their birth family might not be an ideal option for many females exiting residential care (Coler, 2018; Dutta, 2017a; Pryce et al., 2016; Sulimani-Aiden, 2020). According to Pasli and Aslantürk (2024), females were more likely to be removed from families due to neglect and abuse, which led to the lowest sense of belonging within their family context, compared with other reasons such as poverty and absence of parents, which were more common among males. Some statements by female participants in a Canadian study conducted by Prévost-Lemire et al. (2024) vividly explained why many of them were reluctant to return to their family –victims of abuse, returning to live with parents who were the perpetrators, could evoke complex emotions, encompassing shame and expectations that were often difficult to fulfil. Another young mother expressed her concern that her child might be subjected to abuse reminiscent of her own childhood experiences, which compelled her to leave (Prévost-Lemire et al., 2024). Moreover, the emotional and financial support that could be obtained from a birth family was reportedly very limited due to poverty and other complexities experienced by existing family members (Berejena Mhongera & Lombard, 2016; Frimpong-Manso et al., 2022; Van Breda & Hlungwani, 2018).

Good friendships provided these young women with a sense of security and belonging. Some participants mentioned the support offered by friends (including old peers from institutional care and new friends made after leaving care) and their families, such as emotional support, temporary accommodation and inclusion (Berejena Mhongera & Lombard, 2017; Coler, 2018; Dutta, 2017b; Hlungwani & van Breda, 2020; Pryce et al., 2016; Van Breda & Hlungwani, 2019). Some young women also appreciated former staff with whom they had good rapport for their professional assistance in accessing employment, housing and available resources (Coler, 2018; Dutta, 2017b; Purtell et al., 2022; Van Breda & Hlungwani, 2019).

Housing

Care leavers transitioning from both residential care and foster care were more likely to experience homelessness compared with their peers with no in-care experience, and residential care leavers were reported to have poorer housing outcomes than their peers exiting from other types of placements once their after-care support ended (Gypen et al., 2022; Purtell et al., 2022). Accessing secure housing seemed to be a challenge for most females exiting residential care, and the most common housing options were: renting independently with NGOs and government support; returning to original family; and residing with the family of their partner or in accommodation provided by employers, hostels and group homes (Coler, 2018; Dutta, 2017a, 2017b). Female participants in many studies raised additional challenges and barriers in housing; for example, mobility due to relationship breakdown and short-term contracts, uncomfortable living conditions, strict rules in hostels, lack of privacy and security, extensive household chores in exchange for accommodation and inadequate post-18 support (Berejena Mhongera & Lombard, 2017; Dutta, 2017a, 2017b; Gypen et al., 2023). For these reasons, some participants advocated for secure accommodation provided by relevant programmes because of the limited support available to them, and the associated difficulties in securing accommodation and their needs in education (Berejena Mhongera, 2017).

Pregnancy and parenting

Care leavers were more likely to experience early pregnancy compared with young women without child protection involvement, and the experience in residential care further exacerbated this risk due to placement instability and negative peer influence (Purtell et al., 2021, 2022). Ten out of ten participants in a study conducted in Ghana and Uganda admitted that their first pregnancy was an accident without proper preparation (Frimpong-Manso et al., 2022). These young mothers reported that they lacked knowledge of safe sex, pregnancy and intimate relationships before getting pregnant, and limited support and guidance from families after leaving care exacerbated the issue of risky sex and unplanned pregnancy (Frimpong-Manso et al., 2022; Purtell et al., 2022). Female care leavers in Australia reported that they experienced familial belonging, freedom and autonomy through becoming pregnant and starting their own family (Purtell et al., 2021, 2022).

According to many studies, early parenthood posed an adverse impact on young mother’s leaving-care journey, including close association with lower achievement in education, higher reliance on social support, unemployment, homelessness or housing instability, limited parenting resources, inadequate financial support, social isolation and discrimination against both mothers and children and emotional pressure (Frimpong-Manso et al., 2022; Hlungwani & van Breda, 2020; Kääriälä et al., 2019; Lanctôt & Turcotte, 2018; Parry et al., 2023). Young mothers additionally expressed their fear of their pregnancy being exposed and resulting in subsequent exclusion by institutions in Uganda and Ghana throughout the gestational period (Frimpong-Manso et al., 2022). The lack of parenting model and post-18 support, particularly for women with babies, were also considered as key challenges to many young mothers (Purtell et al., 2021). In addition, a violent partner was another challenge that young mothers suffered from, which intensified their feeling of helplessness and despair regarding their pregnancy, the baby they were carrying and their own future (Frimpong-Manso et al., 2022; Lanctôt & Turcotte, 2018).

Conversely, participants in a few studies presented strong resilience in parenting, helping them embrace caring responsibilities and, despite their struggles, providing hope and motivation for the future (Frimpong-Manso et al., 2022; Hlungwani & van Breda, 2020; Lanctôt & Turcotte, 2018; Van Breda & Hlungwani, 2019). Compared with male care leavers, who were strongly against having children, females appeared more open to childbirth and taking on childcare duties (Gabriel et al., 2021; Hlungwani & van Breda, 2020). Although these female care leavers had some difficulties in their parent–child relationships, such as self-doubting, they expressed their strong willingness and passion in taking care of their children (Hlungwani & van Breda, 2020; Lanctôt & Turcotte, 2018; Prévost-Lemire et al., 2024). By caring for their children, they found a sense of belonging and fulfilment (Lanctôt & Turcotte, 2018; Purtell et al., 2021). Notably, their motherhood was largely impacted by their birth family and their experiences in care (Coler, 2018; Gabriel et al., 2021; Hlungwani & van Breda, 2020). These young women reported that their understanding of what makes a good mother was lacking, but they had experience in dealing with bad parents (Lanctôt & Turcotte, 2018; Van Breda & Hlungwani, 2019). These female care leavers were extremely mindful of ensuring that their own children do not experience the maltreatment they endured, by cutting off intergenerational trauma, leaving aggressive fathers, fully supporting and trusting their children, avoiding drug and alcohol misuse and insulating children from any dangerous influences (Lanctôt & Turcotte, 2018; Prévost-Lemire et al., 2024; Purtell et al., 2021).

Sadly, young mothers with in-care experiences were more likely than young mothers without care experience to be subjected to surveillance due to their history with the child protection system, and excessive monitoring can have significant negative impacts on parenting (Purtell et al., 2021). Young women with in-care experiences were expected to raise their children with very limited resources and support that was more focused on scrutinising and assessing the safety of their children being with them rather than the mothers’ real needs (Purtell et al., 2021). Some participants in Lanctôt and Turcotte (2018)’s study similarly felt that they were being scrutinised and were reluctant to seek help, fearing that others might perceive them as incompetent mothers due to their in-care experiences. As a result, they desperately aimed to be good mothers and not make any mistakes (Lanctôt & Turcotte, 2018). To become the ideal mother they envisioned, they imposed stringent requirements on themselves that caused additional emotional and material stress and, at the same time, unintentionally isolated themselves from the personal leisure experienced by woman without care experience (Lanctôt & Turcotte, 2018).

Resilience and future-oriented

Although these young women had suffered from adverse history, many of them expressed aspirational goalsfor the future (Dutta, 2017b; Parry et al., 2023). According to Van Breda and Hlungwani (2019), young women transitioning from residential care showed confidence and resilience in dealing with difficulties because they had had experienced and overcome traumas and adversities before leaving care. Even though some participants were reported to experience ongoing challenging events, such as financial hardship and instable housing, they firmly believed that they had the ability to manage these matters and that a brighter future awaited them (Frimpong-Manso et al., 2022; Van Breda & Hlungwani, 2019). Furthermore, this sense of confidence and resilience could be highly beneficial throughout their life trajectory (Dutta, 2018).

Discussion and implications

It is evident from the key findings of this scoping review that young women exiting residential care have different leaving-care experiences to their male peers. In contrast to males, the reasons for females being placed in care are more related to exposure to violence and abuse than for males, including forms of sexual exploitation and assault, and this is particularly the case in some Global South countries. Similarly, the factors underlying the timing and context of young women leaving residential care may also be gender-specific. Apart from the termination of child protection orders, young women may experience sudden eviction due to family reunion, career development, arranged marriages, pregnancy and deemed misbehaviours.

After the transition from care to emergent adulthood, young women are reported to experience various challenges, including school-dropouts due to external factors, unemployment, financial difficulties, homelessness, isolation and discrimination. Moreover, females attach great significance to supportive relationships such as romantic relationships, links with original families including birth parents, friendships, and wider community connections. These relationships are perceived to be helpful in many cases; however, not all relationships bring benefits. Some may lead to unfavourable outcomes as a result of staying in unhealthy relationships. Additionally, females may achieve better outcomes than males in other domains such as higher educational performance, lower criminal activities, and stronger resilience. Although early pregnancy is widely framed as a concern in articles from both Global North and Global South countries, many young mothers broadly embrace motherhood, take on the responsibilities and transform it into an empowering experience.

As mentioned above, the unique experiences and challenges faced by female care leavers transitioning from residential care before, during and after their transition have been highlighted in numerous articles across a wide range of fields. Three main contexts (the cultural context, the social context and the political context) must be taken into consideration when analysing the contributing factors of these issues and identifying implications for policy and practice.

The most evident manifestation within the cultural context is the adverse impact of traditional gender roles. Rather than being provided support to achieve personal development in education or employment, many female care leavers are endowed with greater familial responsibilities in taking care of all family members including elders and minors, and this expectation is particularly pronounced in some culturally conservative countries (Berejena Mhongera, 2017; Hlungwani & Van Breda, 2020; Sulimani-Aiden, 2020). Female care leavers in patriarchal societies may define the success of their transition through the establishment of successful relationships and marriages, and become heavily reliant on partners and their families (Berejena Mhongera, 2017; Van Breda & Hlungwani, 2019). Moreover, in countries like India, arranged marriage by the institutions is culturally appropriate and seen as one of the preferred pathways after leaving care (Dutta, 2018).

These cultural factors may lead to a certain singularity and lack of options in the pathways forward for young women leaving care. Some long-term awareness changes might be needed to weaken the negative side of cultural effects; for example, self-awareness raising, gender equality education, and encouraging men to share family and caring responsibilities (Grau Grau et al., 2021). Practically, it is important for residential care workers to recognise the gender and power inequality issue faced by these young women, as well as the power differentials between workers and clients (Alston & McKinnon, 2005). With this awareness in mind, staff in residential care setting should be encouraged to challenge traditional stereotypes, empower young women by involving them in decision making and self-determination, and foster equity by respecting young women’s real needs and linking them to relevant services (Alston & McKinnon, 2005). At the same time, of the effects of some cultural factors should be further enhanced, such as a sense of family-belonging and resilience that may come from their family roles (Lanctôt & Turcotte, 2018; Purtell et al., 2021).

Findings show that the level of positive and negative factors varies across different social contexts. In terms of barriers impeding the transitions of young women out of care in a social context, social isolation and discrimination due to in-care experience is discussed in many research articles. Care leavers from residential care in a number of countries are reported to have poor self-esteem because of disparaging voices and stigmatisation from peers, neighbours and communities (Berejena Mhongera, 2017; Pryce et al., 2016; Whitelaw, 2024). Apart from the external pressure from society, female residential care leavers are more likely to have a fragile safety net, including less informal support from family, former carers and friends than their male peers, and little formal support from government (Zhao & Waugh 2025). Moreover, some young women choose to end their connections with formal and informal support networks due to unpleasant experiences (Purtell et al., 2022).

Gender-based inequalities and power dynamics unbalanced to the detriment of women further place young women leaving care in a riskier situation than young men of being exposed to unhealthy relationships, sexual abuse and exploitation (Berejena Mhongera & Lombard, 2017; Dutta, 2017b; Pryce et al., 2016; Van Breda & Hlungwani, 2019). Reducing the prejudice towards care leavers and improving gender equality more generally may be very complicated in practice and require fundamental changes in society. However, reforms in residential care facilities and programs may represent a crucial first step in driving meaningful progress. Alston and McKinnon (2005) suggested that the development of feminist women’s services may help to relieve women from social oppression and provide gender-appropriate services. Such services and programs would allow the facilitators and organisations to focus on structural change instead of normalising the injustice by requiring them to adapt to it.

To mitigate care leavers’ reluctance towards using post-care support services, many scholars recommend a trauma-informed and relationship-based approach in services provided during and after leaving care (Chavulak & Mendes, 2022; Purtell et al., 2022; Zhao & Waugh, 2025). Given the high risks of women including female care leavers being subjected to various forms of violence, it is essential to avoid re-traumatisation when working with them and to foster a safe place for them to recover and heal. In parallel with a trauma-informed approach, it is also necessary to adopt relationship-based practice. This is because females are reported to value relationships more than males (Lanctôt, 2020; Van Breda & Hlungwani, 2019), and trustworthy and consistent relationships with these young women will help agencies and workers to better support and engage with them in- and after-care.

Politically, 16 Global South and 15 Global North jurisdictions have been included in this review. Although local child protection and welfare systems differ across countries, there are several common issues that can be regarded as contributing factors to unfavourable leaving-care outcomes. Primarily, care leavers often experience an inadequate transition planning process that is typified by insufficient training in independent living skills and rare participation of young people in this stage. Many female care leavers transitioning from residential care in Global South countries additionally reported their concern about sudden eviction from support programs due to inappropriate behaviours and pregnancy, which severely restricts the time available for them to prepare (Dutta, 2017a; Frimpong-Manso et al., 2022). Limited and inaccessible post-care support services is another vital contributing factor due to inadequate government funding, lack of public transport and limited access to material and human resources, particularly in some developing countries (Berejena Mhongera & Lombard, 2016).

Nowadays, many scholars from Global North countries advocate for extended care until at least 21 years of age as one of the most efficient mechanisms for improving leaving-care support and corresponding outcomes (Mendes et al., 2023; Zhao & Waugh, 2025). For example, the Midwest study in the USA found a significantly positive association between participation in extended care programs and a lower risk of early pregnancy at ages 17 to 19 (Courtney, 2019). In Australia, although all eight jurisdictions have introduced various forms of extended care policies in response to the Home Stretch advocacy campaign, specific policies and services tailored for supporting residential care leavers and female care leavers still require further development (Mendes, 2023; Zhao & Waugh, 2025).

Limitations and further research

As a scoping review based on scholarly databases only, there are a few limitations that may influence the accuracy and representativeness of the findings. First, terminology disparities among countries could hinder the comprehensiveness of searches and outcomes in the searching process. Another key limitation to note is the possibility of inaccuracies in certain data findings during the coding and data analysis process. The ambiguity in some articles about whether their findings are specific to female care leavers transitioning from residential care, or alternatively apply to female care leavers more broadly, suggests that some results in this study may not be uniquely tied to the residential care setting. Lastly, due to the space limitation, this article focuses solely on scholarly articles. Another search on grey literature databases has been conducted and its findings will be detailed in follow-up publications.

As displayed in the findings of this study, female care leavers transitioning from residential care are reported with various unique challenges compared with males. However, this marginalised group is understudied, particularly in some Global North countries. The information relevant to young women exiting residential care in existing research studies in Global North countries is more likely to be presented as a small component of research findings rather than the main focus. While some studies in Australia delve into residential care and others explore the parenting issues of female care leavers, there is a noticeable gap in research on the general experiences of female care leavers transitioning from residential care. Therefore, this study calls for feminist studies involving females’ voices and perspectives on their overall experiences leaving residential care, aiming to seek social justice and advocate for more appropriate support benefiting this particular group in Australia (Cree, 2018; Seigfried, 1996). Their lived experiences may serve as a key foundation in forming the knowledge in this field and influencing policy and program reforms in the future.

References

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). (2025). Child protection: glossary. Canberra: Australian Government. aihw.gov.au https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports-data/health-welfare-services/child-protection/glossary#R

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). (2024a). Child protection Australia 2021–22. Canberra: Australian Government. aihw.gov.au https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/child-protection/child-protection-australia-2021-22/contents/insights/supporting-children

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). (2024b). Specialist homelessness services clients experiencing family and domestic violence: Interactions with out-of-home care and income support. Canberra: Australian Government. aihw.gov.au https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/family-domestic-and-sexual-violence/shs-clients-experiencing-fdsv-interactions

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), (2022). Child protection Australia 2020–2021. Canberra: Australian Government. aihw.gov.au https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/child-protection/child-protection-australia-2020-21/contents/out-of-home-care/characteristics-of-children-in-out-of-home-care

Alston, M., & McKinnon, J. (2005). Social work: Fields of practice. 2nd edn. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Barker, B., Harris, D., & Brittle, S. (2022). Showing the Light: Young parents with experience of the care system. Canberra: ARACY. aracy.org.au https://www.aracy.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/ARACY_Showing_the_Light_FINAL_20220302-1.pdf

Baynes-Dunning, K., & Worthington, K. (2013). Responding to the needs of adolescent girls in foster care. Georgetown Journal on Poverty Law & Policy, 20(2), 321–349. karenworthington.com https://karenworthington.com/uploads/2/8/3/9/2839680/adolescent_girls_in_foster_care.pdf

Berejena Mhongera, P. (2017). Preparing for successful transitions beyond institutional care in Zimbabwe: Adolescent girls’ perspectives and programme needs. Child Care in Practice, 23(4), 372–388. DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/13575279.2016.1215291

Berejena Mhongera, P., & Lombard, A. (2016). Poverty to more poverty: An evaluation of transition services provided to adolescent girls from two institutions in Zimbabwe. Children and Youth Services Review, 64, 145–154. DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.03.013

Berejena Mhongera, P., & Lombard, A. (2017). Who is there for me? Evaluating the social support received by adolescent girls transitioning from institutional care in Zimbabwe. Practice, 29(1), 19–35. DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/09503153.2016.1185515

Bond, S. J. (2017). The development of possible selves and resilience in youth transitioning out of care. PhD Thesis, University of Johannesburg, South Africa. ujcontent.uj.ac.za https://ujcontent.uj.ac.za/esploro/outputs/doctoral/The-development-of-possible-selves-and/9913510307691

Cassarino-Perez, L., Bedin, L. M., Schutz, F., Sarriera, J. C., Wise, S., McNamara, P., & Montserrat, C. (2019). Educational background, educational expectations and organized activity participation among adolescents aging out of care in Brazil. In P. McNamara, C. Montserrat & S. Wise (Eds). Education in out-of-home care: International perspectives on policy, practice and research. (pp. 283–297). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. DOI https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26372-0_20

Chavulak, J., & Mendes, P. (2022). What does international research identify as the best practice housing pathways for young people transitioning from out of home care? Institutionalised Children Explorations and Beyond, 9(2), 202–214. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/23493003211064369

Coler, L. (2018). “I need my children to know that I will always be here for them”: Young care leavers' experiences with their own motherhood in Buenos Aires, Argentina. SAGE Open, 8(4), 1–8. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244018819911

Coll, K. M., Steward, R. A., Scholl, S., & Hauser, N. (2022). Interpersonal strengths and family involvement for adolescents transitioning from therapeutic residential care: An exploratory study. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 39(1), 81–95. DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/0886571X.2021.1985684

Courtney, M. E. (2019). The benefits of extending state care to young adults: Evidence from the United States of America. In V. R. Mann-Feder & M. Goyette (Eds). Leaving care and the transition to adulthood: International contributions to theory, research, and practice. (pp. 131–148). New York, USA: Oxford University Press. DOI https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190630485.003.0008

Courtney, M., Dworsky, A., Cusick, G. R., Havlicek, J., Perez, A., & Keller, T. (2007). Midwest evaluation of adult functioning of former foster youth: Outcomes at age 21. Chicago, USA: Chapin Hall Center for Children at the University of Chicago. chapinhall.org https://www.chapinhall.org/wp-content/uploads/Midwest-Eval-Outcomes-at-Age-21.pdf

Cree, V. (2018). Feminism and social work: Where next for an engaged theory and practice? Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work, 30(3), 4–7. DOI https://doi.org//10.11157/anzswj-vol30iss3id545

Desmond, C., Watt, K., Saha, A., Huang, J., & Lu, C. (2020). Prevalence and number of children living in institutional care: Global, regional, and country estimates. The Lancet: Child & Adolescent Health, 4(5), 370–377. DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30022-5 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32151317

Department of Families, Fairness and Housing (DFFH). (2018). Family & children: Residential care. Melbourne: Victoria Government. services.dffh.vic.gov.au https://services.dffh.vic.gov.au/residential-care

Department of Social Services (DSS). (2011). An outline of national standards for out-of-home care. Canberra: Australian Government. dss.gov.au https://www.dss.gov.au/outline-national-standards-out-home-care-2011/what-out-home-care

Dutta, S. (2017a). Experiences of young Indian girls transitioning out of residential care homes. Asian Social Work and Policy Review, 11(1), 16–29. DOI https://doi.org/10.1111/aswp.12107

Dutta, S. (2017b). Life after leaving care: Experiences of young Indian girls. Children and Youth Services Review, 73, 266–273. DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.12.022

Dutta, S. (2018). Preparation for social reintegration among young girls in residential care in India. International Journal of Child, Youth & Family Studies, 9(2), 151–170. DOI https://doi.org/10.18357/ijcyfs92201818217

Faith to Action Initiation. (2016). Transitioning to family care for children: A guidance manual. faithtoaction.org https://www.faithtoaction.org/global-statistics-about-children-in-residential-care/

Fairhurst, K., David, L., & Corrales, T. (2016). Baby and me: Exploring the development of a residential care model for young pregnant women, and young women with babies, in out of home care. Melbourne: Anglicare Victoria. anglicarevic.org.au https://www.anglicarevic.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/488_BabyAndMe_v5.pdf

Farber, N. (2014). The not-so-good news about teenage pregnancy. Social Science and Public Policy, 51(3), 282–287. DOI https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-014-9777-y

Frimpong-Manso, K., Bukuluki, P., Addy, T. N. A., Obeng, J. K., & Kato, F. (2022). Pregnancy and parenting experiences of care-experienced youth in Ghana and Uganda. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal, 39(6), 683–692. DOI https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-022-00829-5 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35309088%20

Gabriel, T., Keller, S., & Bombach, C. (2021). Vulnerability and well-being decades after leaving care. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 577450. DOI https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.577450 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33584465

Grau Grau, M., Ias Heras Maestro, M., & Riley Bowles, H. (2021). Engaged fatherhood for men, families and gender equality: Healthcare, social policy, and work perspectives. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. DOI https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-75645-1

Gwenzi, G. D. (2023a). Provision of transitional housing: A socially sustainable solution for care leavers in Zimbabwe. Practice, 35(2), 103–120. DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/09503153.2022.2083100

Gwenzi, G. D. (2023b). The transition from institutional care to adulthood and independence: A social services professional and institutional caregiver perspective in Harare, Zimbabwe. Child Care in Practice, 25(3), 248–262. DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/13575279.2017.1414034

Gill, A., & Luu, B. (2025). A population-based analysis of birth rates and placement patterns among care-experienced young women in New South Wales, Australia. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. DOI https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-024-00995-8

Gypen, L., Stas, L., West, D., Van Holen, F., & Vanderfaeillie, J. (2023). Longitudinal outcomes of employment, income and housing for Flemish care leavers. Developmental Child Welfare, 5(1), 36–58. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/25161032231157094

Gypen, L., West, D., Stas, L., Verheyden, C., Van Holen, F., & Vanderfaeillie, J. (2022). The key role of education for Flemish care leavers. Developmental Child Welfare, 4(4), 253–269. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/25161032221124330

Hlungwani, J., & van Breda, A. D. (2020). Female care leavers' journey to young adulthood from residential care in South Africa: Gender-specific psychosocial processes of resilience. Child & Family Social Work, 25, 915–923. DOI https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12776

Home Stretch. (2025). About us: What have we achieved so far? Melbourne: The Home Stretch. thehomestretch.org.au https://thehomestretch.org.au/learnmore/

Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI). (2024a). Developing the title and question. jbi-global-wiki.refined.site https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/355862667/10.2.2+Developing+the+title+and+question

Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI). (2024b). Inclusion criteria. jbi-global-wiki.refined.site https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/355862707/10.2.4+Inclusion+criteria

Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI). (2024c). Search strategy. jbi-global-wiki.refined.site https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/355862729/10.2.5+Search+Strategy

Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI). (2024d). Source of evidence selection. jbi-global-wiki.refined.site https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/355862749/10.2.6+Source+of+evidence+selection

Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI). (2024e). Data extraction. jbi-global-wiki.refined.site https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/355862769/10.2.7+Data+extraction

Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI). (2024f). Analysis of the evidence. jbi-global-wiki.refined.site https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/355862791/10.2.8+Analysis+of+the+evidence

Kääriälä, A., Haapakorva, P., Pekkarinen, E., & Sund, R. (2019). From care to education and work? Education and employment trajectories in early adulthood by children in out-of-home care. Child Abuse & Neglect, 98, 104144. DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104144 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31678608

Lamb, G. (2023, 1 August). Weeks 4 and 5 Library session: Locating research – Library session [lecture notes]. lms.monash.edu https://lms.monash.edu/mod/folder/view.php?id=11697056&forceview=1

Lanctôt, N. (2020). Child maltreatment, maladaptive cognitive schemas, and perceptions of social support among young women care leavers. Child & Family Social Work, 25(3), 619–627. DOI https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12736

Lanctôt, N., & Turcotte, M. (2018). The 'good mother' struggles: Obstacles to the attainment of motherhood ideals among adult women formerly placed in residential care. Child & Family Social Work, 23(1), 80–87. DOI https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12386