Article type: Original Research

3 September 2025

Volume 47 Issue 2

HISTORY

RECEIVED: 9 April 2025

REVISED: 15 July 2025

ACCEPTED: 31 July 2025

Article type: Original Research

3 September 2025

Volume 47 Issue 2

HISTORY

RECEIVED: 9 April 2025

REVISED: 15 July 2025

ACCEPTED: 31 July 2025

![]() Trauma-informed youth justice case management: A policy audit and survey of staff perspectives

Trauma-informed youth justice case management: A policy audit and survey of staff perspectives

Affiliations

1 School of Psychology, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA 5005, Australia

2 School of Public Health, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA 5005, Australia

3 School of Social and Political Sciences, University of Melbourne, Vic. 3010, Australia

4 School of Health Science, Swinburne University of Technology, Hawthorn, Vic. 3122, Australia

Correspondence

*A/Prof Catia Malvaso

Contributions

Carolyn Boyd - Study conception and design, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting of manuscript, Critical revision

Gene Mercer - Analysis and interpretation of data, Critical revision

Andrew Day - Study conception and design, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting of manuscript, Critical revision

Rhiannon Pilkington - Study conception and design, Analysis and interpretation of data, Critical revision

Catia Malvaso - Study conception and design, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting of manuscript, Critical revision

Carolyn Boyd1

Gene Mercer2

Andrew Day3,4

Rhiannon Pilkington2

Catia Malvaso1,2 *

Affiliations

1 School of Psychology, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA 5005, Australia

2 School of Public Health, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA 5005, Australia

3 School of Social and Political Sciences, University of Melbourne, Vic. 3010, Australia

4 School of Health Science, Swinburne University of Technology, Hawthorn, Vic. 3122, Australia

Correspondence

*A/Prof Catia Malvaso

CITATION: Boyd, C., Mercer, G., Day, A., Pilkington, R., & Malvaso, C. (2025). Trauma-informed youth justice case management: A policy audit and survey of staff perspectives. Children Australia, 47(2), 3062. doi.org/10.61605/cha_3062

© 2025 Boyd, C., Mercer, G., Day, A., Pilkington, R., & Malvaso, C. This work is licensed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence

Abstract

Youth justice services have recently shown interest in developing and implementing new models of practice. Trauma-informed practice has emerged as a promising approach to the case management of justice-involved young people in this context. However, little is known about the extent to which a trauma-informed approach is consistent with current practice or the extent to which guiding policies support and embrace core trauma-informed principles. The aim of this paper is to illustrate the extent to which a youth justice service might be considered receptive and ready to adopt a new model of care. This study reports the findings of a policy audit and workforce survey of community youth justice staff in one Australian jurisdiction, South Australia. Content analysis of 28 policy documents indicated modest alignment between the jurisdiction’s youth justice case-management policies and key principles of trauma-informed practice. Descriptive statistics obtained from workforce survey responses (n = 34) indicated strong endorsement of these principles by youth justice case managers in relation to both individual practice and to case-management administration. Practitioners also identified opportunities for supporting workforce development in trauma-informed practice, reflective practice and policy and organisational reform. The findings suggest a need to review and update the current policy suite to provide an authorising environment to support the implementation of trauma-informed practice. This paper advances knowledge about the type of jurisdiction-wide strategic planning, and the development of policy, needed to enshrine trauma-informed principles – specifically: safety; trust and transparency; choice; empowerment; collaboration; and cultural, historical and gender responsiveness.

Keywords:

case management, juvenile justice, trauma-informed care, trauma-informed practice, youth justice.

Introduction

These are, arguably, times of opportunity for significant change in youth justice services around the Western world. Recent years have seen numerous concerns raised about the quality of services that are provided to justice-involved children and young people, most of which are documented in a series of major reviews of both policy and practice in Australia and elsewhere (e.g. Clancey et al., 2020). These reviews have, in the main, focused either on the need to strengthen the quality of implementation of the current approach to case management (the risk-management approach; see Brogan et al., 2015) or on the need to develop new models of care (as evident in the ‘child-first’ policies of the UK (see Case & Hazel, 2023) or in trauma-responsive youth justice practice frameworks (see Malvaso et al, 2024a)). And yet, external observers and academics have tended to be somewhat cautious – if not cynical – about the impact of these reforms on actual case management and, in fact, have suggested that policy reform by itself may result in little discernible change in everyday practice (e.g. Day, 2023; Day & Malvaso, 2024). One of the most significant challenges that arises here is the inherent tension between controlling the risks of re-offending that are posed by children and young people whilst simultaneously fulfilling a legislative and policy mandate to protect the rights of the child, to address the needs of First Nations families and communities, and to address the welfare and wellbeing needs of children and young people. This is compounded by guiding legislation that has been described as ‘fragmented and confused’, and which contributes to an essentially ‘bifurcated system of ‘care’ for some children and ‘control’ for other children that is largely based on age or type of offence committed’ (Malvaso et al., 2024b: p. 467). It has been argued that some of the consequences of this include the overuse of custody as a common response to youth crime, as well as investment in a wide range of different services and programs for children and young people; from those that might be regarded as ‘punitive’, such as boot camps, through to those that might be considered more ‘restorative’, such as diversion to family conferences (Malvaso & Day, 2025). Concerns have also been expressed about rushing too quickly into reforms, such as trauma-informed practice, before the theoretical and methodological frameworks needed to collect the evidence required to design and implement transformative services and interventions have been developed (Jones et al., 2024). However, what is clear is that any efforts towards reform will need to navigate the realities of a system that has not been designed, primarily, to promote psychological, emotional, cultural, spiritual and physical safety.

Much has been written about how organisational change in youth justice might best be realised, whether this be through legislative reform (e.g. Malvaso et al., 2024b), executive leadership (e.g. Butcher et al., 2024), and/or engagement with First Nations communities (e.g. Butcher et al., 2021). The most widely employed approach to change has been to invest in workforce development through, for example, the provision of continuing professional development programs (e.g. Purtle, 2020). However, while staff training, supervision and support are widely recognised as key features of change implementation (Branson et al., 2017), the formulation and communication of formal policies that describe the change are also important (Aarons et al., 2011). In relation to trauma-informed youth justice, such policies could outline the principles and features of trauma-informed practice in the youth justice context (e.g. NCTSN, 2015; SAMHSA, 2014), including how and when they might be applied in particular settings, and any associated barriers or constraints (Branson et al., 2017). Finally, in the early stages of implementation, it is important to gauge the readiness of staff to accept and implement change (Aarons et al., 2011).

The aim of this paper is to illustrate the extent to which a youth justice service might be considered receptive and ready to adopt a new model of care, specifically ‘trauma-informed case management’. It does this in two ways: first through an audit of current policy to establish the extent to which the key principles of a trauma-informed approach are already enshrined in documentation that defines the case-management role; and second, through a staff survey administered across a community youth justice service to establish the level of endorsement that exists for each of these principles in relation to key activities of case management.

The study focuses on one jurisdiction, South Australia, because the youth justice service there has recently made a commitment to changing the way in which young people are case managed. The guiding legislation in South Australia has been described as making the strongest commitment to providing a ‘welfare-oriented’ response to youth crime in Australia, given that the first object of the Young Offenders Act 1993 (SA) is ‘to secure for youths who offend against the criminal law the care, correction and guidance necessary for their development into responsible and useful members of the community and the proper realisation of their potential’ (section 3.1). Importantly, youth justice in South Australia also sits administratively in the Department for Human Services, rather than with justice. The current case-management approach adopted is nonetheless directly informed by a risk assessment and management approach (also known as a risk–needs–responsivity ‘RNR’ approach), at the core of which is an assessment that is intended to lead to targeted interventions towards those judged to be at highest risk of re-offending (see Brogan et al., 2015). However, evidence concerning the increasingly complex needs of the youth justice population (Malvaso et al., 2020), often associated with histories of maltreatment, adversity and trauma (see Hamilton et al., 2024; Malvaso et al., 2020), has prompted the agency to consider moving towards a more trauma-informed model of case management that has been the foundation for reform in other parts of the world (e.g. Hill et al., 2023; Skuse & Matthew, 2015). However, little is known in this jurisdiction about the extent to which a trauma-informed approach is consistent with current practice in South Australia, or indeed the extent to which guiding policies support and embrace core trauma-informed principles.

Trauma-informed youth justice

A trauma-informed approach assumes that justice-involved children and young people cannot assume full responsibility for their behaviour and that the most logical service response is therefore not to punish, but to deliver interventions that strengthen social and emotional wellbeing and promote healing. In this way a trauma-informed approach to youth justice explicitly acknowledges the role of adversity and trauma in the lives of justice-involved young people, including in their pathways to offending (Day et al., 2023). In addition to providing trauma-specific services and treatments (see Branson et al., 2017), the overarching aim of a trauma-informed approach is to provide an environment that is psychologically and physically safe, thereby reducing the potential for re-traumatisation and facilitating opportunities for recovery and growth. To achieve this, jurisdiction-wide strategic planning and the development of policy that enshrines trauma-informed principles – specifically: safety; trust and transparency; choice; empowerment; collaboration; and cultural, historical and gender responsiveness (SAMHSA, 2014; Table 1) – as key to service delivery, is required. Nonetheless, as Jones et al. (2024) have argued, the term ‘trauma-informed’ is one that remains loosely defined, hard to operationalise and, at times, poorly understood, with uncertainty and confusion arising, in part, because of the different terminology that is sometimes used (e.g. trauma-informed care is sometimes used to describe activity at a service level whilst trauma-informed practice typically concerns the work of individual practitioners; there is also a difference between practice that is trauma specific (interventions designed to address trauma and related symptoms), that which is trauma informed (when staff are trained to understand about trauma and its impact) and/or trauma responsive (where organisations and services create a positive environment and have implemented, or amended, policies and practices to minimise the chance of re-traumatisation).

An important point to make about the application of these core principles to practice in a justice context is that a trauma-informed approach does not sit in opposition to efforts to manage or contain risk. Rather, it focuses attention on evidence that as trauma exposure accumulates over time, so too do high-risk behaviours and contacts with the youth justice system (Yoder & Tunstall, 2022). In this way, ‘risk’ is conceptualised in terms of vulnerabilities that arise in response to childhood maltreatment and social and structural inequalities and the different developmental pathways and mechanisms that result in offending (see de Ruiter et al., 2022). Given that trauma reactions are often a catalyst for involvement in the youth justice system, a primary concern is to address ‘criminogenic’ presentations of trauma (e.g. impulsivity, risk-taking and low self-control) as well as to minimise re-traumatisation.

A trauma-informed approach to case management in youth justice does, however, differ from one that is based primarily on risk management in terms of the way in which engagement with the child or young person is identified as critical to effective practice. Bath (2015) discussed this in relation to three ‘pillars’ of care (safety, connections, coping) and Day and Malvaso (2025) discussed how youth justice practitioners will be the most effective agents of positive change when they successfully engage children and young people with a focus upon: (1) listening carefully; (2) helping justice-involved children and young people to feel safe; and (3) working in ways that promote positive and rewarding experiences. These three components, in their view, align to the growing evidence regarding the importance of building meaningful relationships, developing trust, working collaboratively and with compassion, responding effectively to developmental needs (recognising childhood adversities, trauma and disadvantage), and building upon strengths. Finally, in the UK, the HM Chief Inspector of Prisons (2025) set out ‘in stark terms the failure by the Youth Custody Service to create environments in which staff and children in young offender institutions (YOIs) are able to form positive, appropriate relationships’ (p. 3), arguing that that relationships between staff and children in custody are a key element in delivering better outcomes. The use of person-centred language is an important first step towards this, based on the adoption of language that is accurate and does not obscure the person or conflate a person with an act (e.g. ‘young offender’). Similarly, language that suggests membership of a homogeneous group that is defined and stigmatised on the basis of criminal behaviour (e.g. ‘sex offender’) should be avoided in any approach that aspires to be trauma informed (see Jones et al., 2024).

Table 1. Six principles of trauma-informed practice

Adapted from SAMHSA (2014) and Department of Human Services (2022).

| Principle | Description |

|---|---|

|

Safety |

The agency and staff members work to ensure children and young people feel physically, psychologically and culturally safe. The agency also supports staff to feel safe in their work. For staff, children and young people, this means that the physical setting is safe and interpersonal interactions promote a sense of safety. |

|

Trust and transparency |

The agency and staff members work towards building and maintaining trust with children and young people. Trust and transparency occur when children and young people receive clear and open communication about processes and decisions that affect them and what is expected of them. |

|

Choice |

Choice is embedded through actions to support children and young people in shared decision making, choice and goal setting to determine the plan of action they need to heal and move forward. The needs and wishes of children and young people are listened to. Choices are explained clearly and transparently. |

|

Empowerment |

Efforts are made by the organisation to share power and to give children, young people and staff a strong voice in decision making. The concerns of young people are listened to and validated, and young people are supported to make decisions and take action. Children and young people are encouraged to recognise their strengths and offered opportunities to build on them. |

|

Collaboration |

The value of children and young people’s experience is recognised by asking them what they need, working alongside them and actively involving them in service delivery. |

|

Cultural, historical and gender responsiveness |

This principle might be expressed by the organisation: offering access to gender-responsive services; leveraging the healing value of traditional cultural connections; embedding policies, protocols and processes that are responsive to the racial, ethnic and cultural needs of individuals; and recognising and addressing historical trauma. |

Method

This study involved two components: an audit of current policy documents to establish compatibility with a trauma-informed approach; and a survey of youth justice staff to determine the level of support that exists for reforms of this type.

Policy audit

Originally developed to analyse strategic national and state-level health policy in Australia and subsequently adapted to be more specific to child and youth health policy analysis (Phillips, 2019), an existing coding framework (Fisher et al., 2015) was used in this policy audit. This provided a systematic method to deconstruct the text and to make sense of the wide range of policy documents (Patton, 2015), based on the content of documentation (rather than, for example, the quality of implementation). The starting point was to locate the most recent version of each policy and guideline on the Youth Justice intranet site of the South Australian Department of Human Services between January and March 2024. From a total of 60 policies and guidelines provided by the Department, 28 were rated as relevant. These included documents such as the Bail Assessment and Review Guideline (to identify ‘key areas which may impact on a young person’s ability to comply with supervised bail and consideration of intervention to further assist with compliance’) and the Case Management Policy (that states that ‘case management is one method of intervention that youth justice uses as a means of improving client outcomes and meeting its strategic objectives. Also requiring inclusion is any specific condition set by the Youth Court in the bail agreement other than standard conditions, such as random drug testing’). Ratings were then made against each of the six foundational principles of trauma-informed practice (TIP) to document explicit or implicit evidence of alignment. For example, the principle of ‘empowerment’ was identified as explicitly evident within the strategic context of this guideline, which states, ‘… all Youth Justice staff collectively contribute to achieving positive outcomes for our clients by supporting rehabilitation principles and respecting and fostering agency (self-determination)’. However, there was little evidence within the body of the guideline that the principles of empowerment/self-determination feature in any substantive way because the guideline largely set out the procedures and workflows for staff. For each policy document, each TIP principle was scored as either 0 (insufficient, contradictory or no evidence), 1 (some evidence) or 2 (sufficient or significant evidence). Item scores were then summed to create a total score for overall TIP alignment in each document, which could range between 0 and 12. Scores of 3 or less were considered indicative of ‘low’ or ‘no’ alignment, scores between 4 and 8 were indicative of ‘some’ or ‘moderate’ alignment, and scores between 9 and 12 reflected ‘significant’ alignment. One author (GM) reviewed, coded and scored each document (n = 28), and a second author (CM) separately coded a subset of randomly selected documents (n = 8; ~30%). There were no disagreements in scores between reviewers.

Workforce survey

The survey was designed to evaluate the views of youth justice case-management practitioners in relation to the visibility and importance of the key principles of trauma-informed practice to their work. Eligible participants were all practitioners employed in roles relating to case management and/or coordination in Community Youth Justice offices in South Australia or at the State’s youth custodial facility. The survey was conducted via the Qualtrics online survey platform, with eligible staff members receiving an email invitation, together with a link to the survey, from the General Manager of Community Youth Justice. The email outlined the purpose of the survey and emphasised that participation was voluntary and anonymous.

Survey questions were answered using 5-point Likert-type rating scales and were organised into four sections: (1) demographic and employment information; (2) principles considered important to successful case management; (3) principles evident in current case-management approaches; and (4) practitioners’ perceived support to deliver effective case management. Specifically, in Section 2, participants were presented with a brief description of each TIP principle and asked to rate its importance in relation to seven elements of case management: establishing a working relationship with the young person; assessment; case planning; intervention; referral to other services; reviewing and monitoring progress; and rehabilitation and integration of the young person into the community. Response choices ranged from ‘not at all important’ through to ‘extremely important’. In Sections 3 and 4, participants were asked to rate the extent to which each TIP principle was reflected in current case-management practice and in their current working environments, with response options ranging from ‘not at all well’ through to ‘to a very great extent’. Due to the small sample size, data reduction techniques consistent with those recommended by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, such as small cell size suppression (i.e. in cells where the value was <5) and combining response categories, were utilised when reporting to limit risk of re-identification. Following the ratings for each principle, a free-text question invited participants to identify ways in which case managers and coordinators could strengthen implementation of that principle. The survey concluded with a free-text question inviting participants to indicate any other ways in which youth justice could support case managers and case coordinators in their work with children and young people. Content analysis was used to identify themes across responses.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was received from the University of Adelaide’s School of Psychology Human Research Ethics Subcommittee (approval 24/09).

Results

Policy audit

In total, 60 policy documents were identified as potentially relevant to case management, with 28 of these then selected by the Community Youth Justice Operations Manager as of direct importance to case-management practice and included for analysis. The documents included 19 guidelines, 6 policies and 3 procedures, which varied in terms of focus (either very specific or general), format (e.g. policy, guideline or procedure) and length. The majority (n = 23) were last updated 5 or more years ago, with different strategic and operational priorities evident across documents of different ages. As a result, there were often complex, implied interactions between the different policies, procedures and guidelines. A complete list of documents reviewed, and their description, is included in the Supplementary Material.

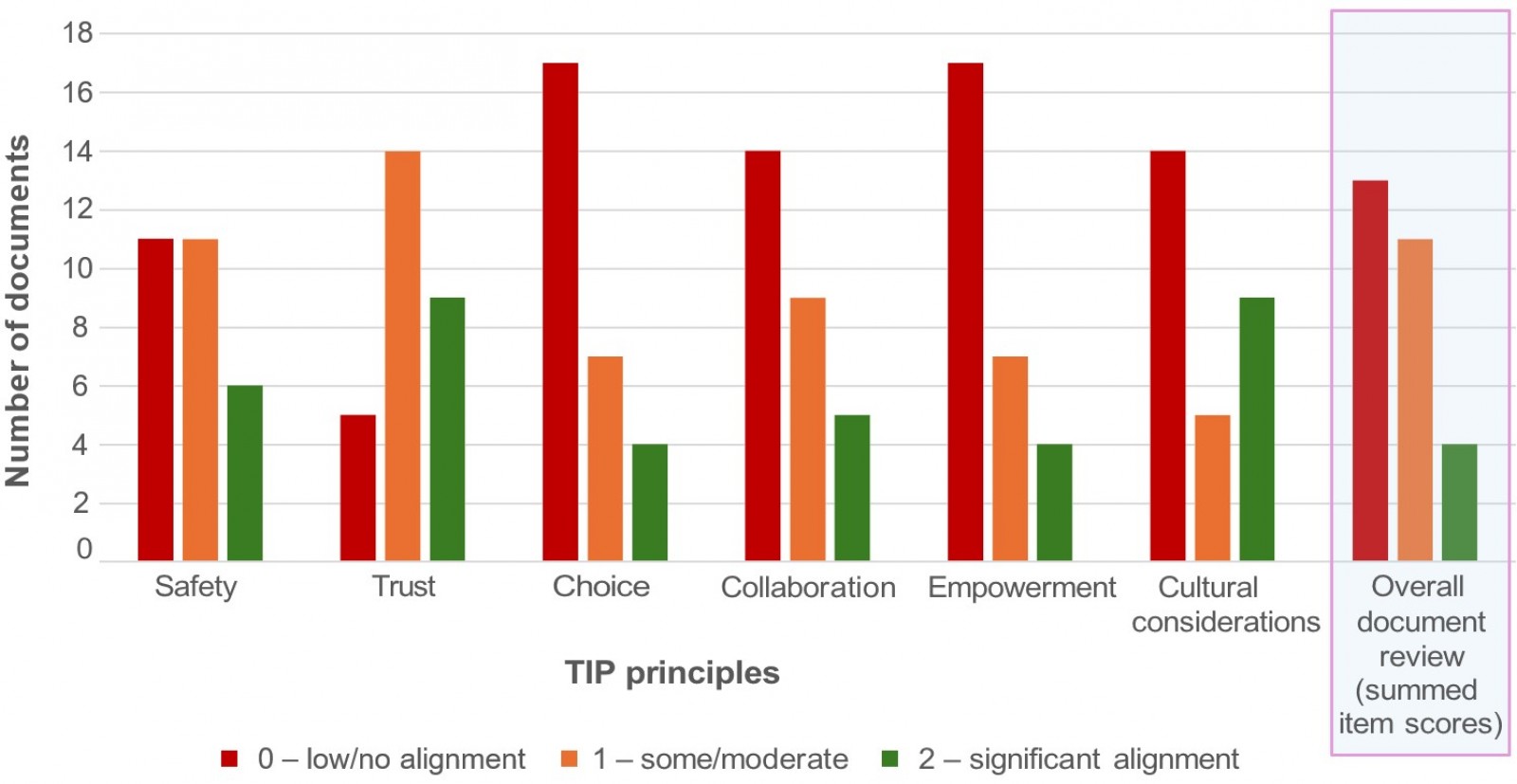

Alignment with TIP principles across the total pool of documents was low; just under half (n = 13) of the documents were rated as showing ‘low’ evidence of alignment, with only four documents rated as having ‘significant’ alignment (Figure 1). When considering ratings of individual TIP principles, choice and empowerment were the most likely to be rated as having low alignment (in 17 of the documents); trust and cultural considerations were most likely to be rated as having significant alignment (in 9, or one-third of the documents).

When focusing on documents that youth justice managers identified as most relevant to case management (n = 12), the Service Delivery Policy and Case Plan and Review Guideline were found to be most closely aligned with TIP principles (both scored 8 out of 12), followed by the Community Assessment and VONIY Guideline (scored 6 out of 12). The Client Supervision and Home Detention policies were rated as having lowest alignment (scores of 1 and 2 out of 12, respectively). The Case Management Policy had moderate alignment (scored 4 out of 12). When considering ratings of individual TIP principles among this set of more relevant documents, trust was the most common principle, rated as having either moderate or high alignment in the majority of documents (in 9 out of 12 of the documents). Despite a legislative mandate to provide tailored services to children of different ages, genders and cultural backgrounds, there was little focus on cultural, historical and gender responsiveness, with only four documents rated as moderately or highly aligned with this principle.

Figure 1. Number of documents (n = 28) aligned with trauma-informed principles (item scores) and overall document review (summed item scores)

Staff survey

Demographic and employment information

Thirty-four out of a potential pool of approximately 50 eligible staff members responded to the survey, representing a response rate of approximately 65%. The majority (31/34; 91%) were employed as case managers in community youth justice settings. Almost 60% (20/34) were female, over 90% were not from an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander background, and almost 40% had more than 10 years’ experience working in youth justice. A majority (24/34; 71%) had a social work degree and worked with young people on both sentenced and unsentenced orders.

Principles considered important to successful case management

Nearly all respondents rated each TIP principle as ‘very’ or ‘extremely’ important to the effective delivery of case management and to their own practice. In terms of the importance of TIP principles to specific case-management activities (Table 2), ‘very important’ and ‘extremely important’ ratings predominated. No participants indicated that any of the principles were ‘not important’ (data not shown), and only a small number of participants rated any of the principles as ‘slightly’ or ‘moderately important’.

Overall, there were some principles of trauma-informed practice that were viewed as less important to specific elements of case management. For example, a quarter of participants rated ‘choice’ and ‘trust’ as only ‘slightly’ or ‘moderately’ important to assessment and case planning, respectively. ‘Empowerment’ was the least-endorsed principle across the majority of elements of case management, whereas ‘collaboration’ was consistently endorsed as ‘very’ or ‘extremely’ important across all elements of case management.

Table 2. Staff ratings of the importance of each trauma-informed practice (TIP) principle to specific case-management activities

No participant rated any of the TIP principles as ‘not at all important’ to any element of case management, so this response category has been excluded from the table. # indicates negligible percentage, which is not specified to ensure anonymity.

| TIP principle | Case-management activity | Response category | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slightly or moderately important | Very important | Extremely important | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Safety | Working relationship | <5 | # | <10 | <20.0 | 28 | 82.4 |

| Assessment | <5 | # | <15 | <35.0 | 19 | 55.9 | |

| Case plan | 5 | 14.7 | 14 | 41.2 | 15 | 44.1 | |

| Intervention | <5 | # | <10 | <20.0 | 26 | 76.5 | |

| Referral | <5 | # | <15 | <35.0 | 21 | 61.8 | |

| Review and monitoring | <5 | # | <15 | <35.0 | 20 | 58.8 | |

| Rehabilitation and reintegration | <5 | # | <10 | <20.0 | 25 | 73.5 | |

| Trust | Working relationship | <5 | # | <10 | <20.0 | 30 | 88.2 |

| Assessment | 6 | 17.6 | 10 | 29.4 | 18 | 52.9 | |

| Case plan | 9 | 26.4 | 7 | 20.6 | 18 | 52.9 | |

| Intervention | <5 | # | <10 | <20.0 | 25 | 73.5 | |

| Referral | <5 | # | <15 | <35.0 | 20 | 58.8 | |

| Review and monitoring | <5 | # | <15 | <35.0 | 20 | 58.8 | |

| Rehabilitation and reintegration | <5 | # | <10 | <20.0 | 25 | 73.5 | |

| Choice | Working relationship | 5 | 14.7 | 7 | 20.6 | 22 | 64.7 |

| Assessment | 9 | 26.5 | 9 | 26.5 | 16 | 47.1 | |

| Case plan | <5 | # | <15 | <35.0 | 21 | 61.8 | |

| Intervention | <5 | # | <15 | <35.0 | 22 | 64.7 | |

| Referral | <5 | # | <15 | <35.0 | 19 | 55.9 | |

| Review and monitoring | <5 | # | <15 | <35.0 | 19 | 55.9 | |

| Rehabilitation and reintegration | <5 | # | <15 | <35.0 | 20 | 58.8 | |

| Empowerment | Working relationship | 6 | 17.6 | 8 | 23.5 | 20 | 58.8 |

| Assessment | 10 | 29.4 | 11 | 32.4 | 13 | 38.2 | |

| Case plan | <5 | # | <15 | <35.0 | 18 | 52.9 | |

| Intervention | <5 | # | <15 | <35.0 | 19 | 55.9 | |

| Referral | 6 | 17.6 | 11 | 32.4 | 17 | 50 | |

| Review and monitoring | 6 | 17.7 | 12 | 35.3 | 16 | 47.1 | |

| Rehabilitation and reintegration | <5 | # | <10 | <20.0 | 22 | 64.7 | |

| Collaboration | Working relationship | <5 | # | <10 | <20.0 | 25 | 73.5 |

| Assessment | <5 | # | <10 | <20.0 | 25 | 73.5 | |

| Case plan | <5 | # | <15 | <35.0 | 20 | 58.8 | |

| Intervention | <5 | # | <15 | <35.0 | 23 | 67.6 | |

| Referral | <5 | # | <15 | <35.0 | 18 | 52.9 | |

| Review and monitoring | <5 | # | <15 | <35.0 | 19 | 55.9 | |

| Rehabilitation and reintegration | <5 | # | <15 | <35.0 | 22 | 64.7 | |

| Cultural, historical, and gender considerations | Working relationship | <5 | # | <10 | <20.0 | 28 | 82.4 |

| Assessment | <5 | # | <10 | <20.0 | 22 | 64.7 | |

| Case plan | <5 | # | <10 | <20.0 | 23 | 67.6 | |

| Intervention | <5 | # | <10 | <20.0 | 26 | 76.5 | |

| Referral | <5 | # | <10 | <20.0 | 28 | 82.4 | |

| Review and monitoring | 5 | 14.7 | 9 | 26.5 | 20 | 58.8 | |

| Rehabilitation and reintegration | <5 | # | <10 | <20.0 | 27 | 79.4 | |

Principles evident in current case-management approaches

Participants’ ratings of how well case managers and case coordinators implemented each principle ranged from ‘slightly well’ to ‘extremely well’, with the most frequent responses being ‘very well’ for the principles of ‘safety’, ‘trust’ and ‘choice’ (Table 3). When responses in the ‘very well’ and ‘extremely well’ categories were combined, the principles most strongly endorsed were ‘trust’ (20/34, 59%) and ‘safety’ (19/34, 56%). The principle with the fewest ratings was ‘responding sensitively to cultural, historical and gender issues’ (16/34, 47%).

No participant rated any TIP principle as ‘not at all well’ implemented, so this response category has been excluded from the table.

Table 3. Staff ratings of how well principles of trauma-informed practice are implemented across case management

| TIP principle | Response categories | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slightly or moderately well | Very or extremely well | |||

| How well do case managers and coordinators … | n | % | n | % |

| Support young people to feel safe (Safety) | 15 | 44.1 | 19 | 55.9 |

| Support building trust with young people (Trust) | 14 | 41.2 | 20 | 58.8 |

| Support children and young people in shared decision making, choice and goal setting (Choice) | 17 | 50.0 | 17 | 50.0 |

| Support the empowerment of children and young people (Empowerment) | 17 | 50.0 | 17 | 50.0 |

| Work collaboratively with children and young people (Collaboration) | 16 | 47.1 | 18 | 52.9 |

| Recognise and respond to cultural, historical and gender issues that affect children and young people (Cultural, historical and gender considerations) | 18 | 52.9 | 16 | 47.1 |

Practitioners’ perceived support to deliver effective case management

Responses about participants’ perceived support to deliver effective case management ranged from ‘not at all’ to ‘a very great extent’ (Table 4). When the responses ‘to a great extent’ and ‘to a very great extent’ were combined, the highest favourable response (55.9%; 19/34) was ‘take active steps to support staff safety and wellbeing’ while the lowest percentage (41.2%; 14/34) was for ‘consult with staff about decisions that affect them’.

Table 4. Staff ratings of perceived support to deliver case management

| Support category | Response category | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not at all or a little | To a moderate extent | To a great extent | To a very great extent | |||||

| To what extent does the youth justice agency … | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Listen and respond to staff concerns about physical and psychological safety | 6 | 17.6 | 10 | 29.4 | 11 | 32.4 | 7 | 20.6 |

| Take active steps to support staff safety and wellbeing | 5 | 14.7 | 10 | 29.4 | 9 | 26.5 | 10 | 29.4 |

| Communicate openly and honestly with staff | 11 | 32.3 | 7 | 20.6 | 9 | 26.5 | 7 | 20.6 |

| Look out for the best interests of staff | 7 | 20.6 | 10 | 29.4 | 11 | 32.4 | 6 | 17.6 |

| Consult with staff about decisions that affect them | 12 | 35.3 | 8 | 23.5 | 7 | 20.6 | 7 | 20.6 |

| Encourage staff to recognise and build on their strengths | 7 | 20.6 | 12 | 35.3 | 7 | 20.6 | 8 | 23.5 |

| Acknowledge and respond sensitively to cultural, historical and gender issues that affect staff | 8 | 23.5 | 8 | 23.5 | 11 | 32.4 | 7 | 20.6 |

Participants’ suggestions to strengthen implementation of trauma-informed principles in youth justice case management and coordination

Participants’ free-text responses on how case managers and coordinators could strengthen implementation of specific TIP principles included descriptions of ‘constraints’ and ‘enablers’. As well as suggestions for case managers and coordinators, some responses included recommendations for Youth Justice as an agency (see Table 5). Responses are summarised below.

Constraints

Participants indicated that an important barrier to strengthening implementation was the perceived tension between addressing young people’s physical and psychological needs by focusing on trauma-informed practice and complying with the demands of the youth justice legal mandate by focusing on young people’s criminogenic needs. A reciprocal relationship was noted here: a focus on trauma-informed principles was considered a potential hindrance to legal compliance, while the need for legal compliance was considered to restrict case managers’ capacity to offer young people trauma-informed options (e.g. choices over goals and activities).

Other perceived constraints included a lack of resources to address specific situational needs of children and young people to improve their safety and engagement (e.g. funds to purchase a phone to enable a young person to maintain regular contact with the case manager). One response also noted that prior negative experiences with other service agencies had the potential to hinder the establishment of trust between young people and case managers.

Enablers

Suggested enablers for case managers and coordinators were aligned with the various principles and included: developing a relationship of trust with the young person; demonstrating trustworthiness via honesty, transparency and commitment ; offering opportunities for the young person to exercise choice within the constraints of the legal mandate (e.g. over the frequency and location of contact with the case manager); adopting a strengths-based approach to foster the young person’s capacity for choice, empowerment and collaboration; and prioritising the young person’s best interests through advocacy and communication with other services (empowerment). No specific suggestions for case managers were made in relation to cultural considerations.

The suggested enablers for Youth Justice as an agency included: providing safe and welcoming spaces for young people to meet with case managers; training and mentoring new practitioners in specific aspects of trauma-informed practice (e.g. helping to foster trust and rapport with ‘challenging’ young people); and providing clear guidance in case managers’ role descriptions and elsewhere, to indicate where and how the principles of trauma-informed practice could be implemented within the restrictions of legal mandates.

Further suggestions for youth justice to support case managers and coordinators

The final free-text question of the survey invited respondents to identify ways in which Youth Justice as an agency could further support the work of case managers and coordinators. Rather than focusing on specific trauma-informed principles, these responses addressed issues of workplace management and case management more broadly. The main themes are summarised below:

- Increase training, development and learning resources for case managers and coordinators. Suggestions included: enhanced training, mentoring and supervision for new staff; ongoing professional development to improve practice; opportunities to work in different teams (e.g. policy, custodial) and act in different roles; and provision of an online, interactive practice manual. One respondent recommended having a designated training officer or team.

- Expand and update practice resources for case management. Participants expressed a desire for new assessment and intervention tools, suggesting that current tools are not appropriate or out of date. There was support for expanding the range of available interventions beyond those that address criminal behaviours (e.g. anger management) to include programs that address mental health and employment needs, and/or provide therapeutic support.

- Improve job design for case managers. Participants reported that case managers needed to find a better balance between client work and administration, which could be facilitated by: improving decision making regarding caseload allocation; reducing workload; streamlining administrative tasks; and clarifying roles and responsibilities of case managers and case coordinators and how they are distinct from each other.

- Improve communication and consultation with staff. Participants expressed a desire for greater communication with staff regarding staffing and practice issues, and to advise them in advance of any upcoming organisational change. They also recommended that the agency should listen more to the views of staff with direct client contact, and that staff should be more involved in consultation and discussion over such issues as case complexity and caseload allocation.

- Improve system and agency processes. Suggestions included developing a more integrated practice model that incorporates community and custodial youth justice, and planning and implementing systemic processes to strengthen case management support for young people.

- Provide opportunities for reflective practice and peer support. Participants expressed a desire for reflective practice opportunities and a safe environment for regular peer discussion, debriefing opportunities, effective supervision and peer support, and practice guidelines for staff.

Table 5. Themes emerging from participants’ suggestions to strengthen support for each principle of trauma-informed practice

| TIP principle | Enablers for case managers and coordinators | Enablers for the youth justice agency | Constraints |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Safety |

Focus on building relationship and trust with young person.

Allow young person to exercise choice in meetings (e.g. frequency, location of contact).

Practice core social work values (e.g. self-determination). |

Provide safe, welcoming venues for case managers and coordinators to meet with young people.

Clarify role description (e.g. addressing young person’s safety needs vs criminogenic needs).

Increase workplace support (e.g. supervision, training, leadership, opportunities to discuss safety).

Increase funding and resources to employ support staff, purchase items (e.g. phones) for young people. |

Poor inter- and intra-agency communication and cooperation.

Aspects of intra-role conflict (e.g. addressing young person’s safety needs) interferes with addressing criminogenic needs.

Lack of technology (e.g. young person may not have a phone), which may limit ability to engage.

Lack of funding, resources. |

|

Trust and transparency |

Demonstrate trustworthiness via honesty, transparency, commitment.

Use relational skills to build engagement with young person. |

Increase communication and contact across youth justice business areas (e.g. between community and custodial spaces) and between metropolitan and country/regional youth justice.

Enable mentoring of new staff on fostering trust with challenging young people.

Provide training in rapport and relationship building.

Facilitate joint meetings with family and/or key supports.

Provide technology support to facilitate relationship building (e.g. via online meetings). |

Poor inter- and intra-agency communication and cooperation.

Aspects of intra-role conflict (e.g. addressing young person’s safety needs) interferes with addressing criminogenic needs.

Lack of technology (e.g. young person may not have a phone), which may limit ability to engage.

Lack of funding, resources. |

|

Choice |

Find balance between choice and non-negotiables as stipulated in legal mandate.

Adopt a strengths-based approach.

Apply self-determination principles, seeking feedback, providing multiple options.

Conduct motivational interviewing. |

Provide guidance on when young person can be consulted given statutory nature of work.

Promote a strengths-based approach to case management.

Provide training in motivational interviewing. |

Order conditions (e.g. mandated program attendance) sometimes remove choice from young person.

Lack of resources (e.g. housing and services) makes some goals unattainable.

Lack of engagement by young person and family members can make case planning difficult. |

|

Empowerment |

Adopt a strengths-based approach.

Prioritise young person’s interests through advocacy and communication with other services. |

Provide guidance and tools to discern when appropriate to encourage empowerment. |

Statutory nature of work may limit opportunities for empowerment. |

|

Collaboration |

Emphasise empowerment and choice for young people. |

Improve communication and cooperation across youth justice sites.

Redirect administrative tasks from case managers to courts or administrative staff. |

|

|

Cultural, historical and gender responsiveness |

Provide training on cultural and gender responsiveness. |

Discussion

Case management is the principal way in which services are provided to justice-involved children and young people and involves coordinating services and interventions that are intended to reduce re-offending and build capacity to live positive lives. In a context in which concerns have been expressed about the lack of a comprehensive system of staff capability building for front-line staff (e.g. Rhodes et al., 2021), TIP has been put forward as offering a set of case-management principles to guide case management that respond to the increasing complexity and trauma presentations of the contemporary youth justice population (see Day et al., 2023). The aims of this study were: (1) to establish the extent to which the key principles of a trauma-informed approach are already enshrined in documentation that defines the case-management role; and (2) to establish the level of endorsement that exists for each TIP principle in relation to key activities of case management in an Australian jurisdiction that has recently made a commitment to changing the way in which young people are case managed.

The policy audit revealed obvious opportunities to strengthen the current policy suite to make it more consistent with trauma-informed practice as applied to youth justice case management. Even the most closely aligned documents did not include explicit descriptions of working with justice-involved children and young people in a trauma-informed way. Most of the documents reviewed were outdated or still in draft form, suggesting that an up-to-date suite of policy documents is needed for practitioners to have clear and practical guidance about how to case manage in a trauma-informed way that is also consistent with the objectives of the agency and its legal mandate. This is even in a jurisdiction such as South Australia, where the legislation requires the agency to adopt a child welfare approach to case management, rather than prioritising community safety (see Malvaso et al., 2024b). The completion of work currently underway in this jurisdiction to develop a Youth Justice Practice Framework is critical to the development of a suite of such policies and guidelines that drive case management. This should lead to a more focused and coherent set of documents that can guide case-management reform towards more trauma-informed practice.

The results of this survey of front-line youth justice staff who are involved in case management clearly demonstrate the strength of support that exists for the adoption of TIP. Each TIP principle was overwhelmingly endorsed by staff as important to effective practice, with the principles of ‘safety’ and ‘trust’ receiving universal support. However, staff ratings of the extent to which each principle is enacted in current practice were less consistent, with the principles of ‘empowerment’, and ‘collaboration’ rated as only being ‘moderately well’ implemented. The principle rated as most poorly implemented was ‘responding sensitively to cultural, historical and gender issues’. The principles that are not well implemented represent areas in which efforts to strengthen implementation of a trauma-informed approach might focus, although we would also point out that it is not always clear what a satisfactory operationalisation of each principle would entail (e.g. the principle of trust and transparency focuses both on children as recipients of information and direction, as well as a broader understanding that trust and transparency is also about adults following through with actions). Similarly, it is not always clear what is meant by recognising and addressing historical trauma (under the cultural, historical and gender responsiveness principle). We would also note the disjuncture between the principles that case managers value (or feel equipped to implement in their practice) and those principles that are being prioritised for implementation by different areas within the youth justice agency (e.g. while responding sensitively to cultural, historical and gender issues was the least endorsed principle; nearly half of participants still rated this as being very or extremely well implemented). Nonetheless, the greatest variation in survey responses was evident for questions asking staff to rate the extent to which TIP principles are reflected in perceptions of their own working environments, with more than two-thirds of staff members indicating that they were not often consulted about decisions that affect them. As a starting point, organisational and cultural change efforts could be directed towards ensuring there are strategies and processes in place for incorporating a system for staff consultation and the use of practice wisdom to inform the ongoing development of practice guidance.

Several suggestions were put forward by staff as to how to strengthen implementation of each of the principles and to overcome current constraints or barriers to reform. These included: increased access to training, professional development, learning resources and opportunities for reflective practice and peer support; the updating of practice resources and interventions that are more aligned with a trauma-informed and child-centred approach; improving job design to enable a better balance between client work and administration; and further transparency in decision making by improving communication and consultation with staff. Engaging with, and listening to, the views of staff can provide detailed insights into practice, which can be enhanced through investment in the development of professional skills and training curriculum.

In a sociopolitical context in which calls for the reform of youth justice are common, and in which many services are continually reviewing their current policy and practice frameworks, the findings of this survey are encouraging. Based on an understanding that front-line staff are key to any continuous improvement initiatives (and assuming that a trauma-informed approach is an appropriate response to the increasing complexity of the youth justice population), the results of this study suggest that youth justice staff strongly endorse ways of working that enact the trauma-informed principles. We would argue that despite the tension identified by staff between supporting children’s safety needs and addressing criminogenic need, it is quite possible to develop case-management practice in ways that are more trauma-informed while also remaining consistent with the existing risk-management-focused approach (see above). In fact, staff readily identified several practical suggestions for how this might be achieved.

It is important to acknowledge that most documents included in the policy audit pre-dated the agency’s interest in TIP and, as a result, it is not surprising that these documents were not well aligned with the principles. To move towards organisation-wide implementation of trauma-informed practice, all policy documents would need to be reviewed and updated to promote consistency in the principles, rules and expectations of the agency more broadly, to increase staff confidence in the principles and standards described, to promote compliance and to reduce ad hoc work practices that may develop in response to an absence of clear agency guidance. Similarly, while the staff survey focused on the views and perceptions of front-line practitioners working specifically in case-management-related roles, to promote agency-wide adoption of trauma-informed principles it will be important to identify the broader workforce’s understanding and level of endorsement of trauma-informed practice, including those working in youth worker positions in custodial facilities, those in managerial, policy and executive roles, and those working in administrative support positions.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to support the articulation of ‘trauma-informed youth justice’ and opportunities to enhance the case management of children and young people under supervision in the community by statutory youth justice services from a trauma-informed perspective. The findings of a policy audit of policies and guidelines relating to community case management, and a workforce survey of community youth justice practitioners, in an Australian jurisdiction are reported. We conclude that there is a need to review and update the policy suite to legitimise the implementation of trauma-informed practice, and that there was strong endorsement from the workforce to work in ways that are consistent with principles of this approach. This study illustrates the extent to which a youth justice service might be considered receptive and ready to adopt a new model of care and, in doing so, advances knowledge about the type of jurisdiction-wide strategic planning and the development of policy needed to enshrine trauma-informed principles – specifically: safety; trust and transparency; choice; empowerment; collaboration; and cultural, historical and gender responsiveness.

References

Aarons, G. A., Hurlburt, M., & Horwitz, S. M. (2011). Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 38(1), 4–23. DOI https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21197565

Bath, H. (2015). The three pillars of trauma wise care: Healing in the other 23 hours. Reclaiming Children and Youth, 23, 5–11.

Branson, C. E., Baetz, C. L., Horwitz, S. M., & Hoagwood, K. E. (2017). Trauma-informed juvenile justice systems: A systematic review of definitions and core components. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 9, 635–646. DOI https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000255 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28165266

Brogan, L., Haney-Caron, E., NeMoyer, A., & DeMatteo, D. (2015). Applying the Risk-Needs-Responsivity (RNR) model to juvenile justice. Criminal Justice Review, 40, 277–302. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/0734016814567312

Butcher, L., Day, A., Malvaso, C., & Fernandez, M. (2024). Applying models of leadership to youth justice reform. Journal of Applied Youth Justice, 38, 39–56. DOI https://doi.org/10.52935/24.22120.5

Butcher, L., Day, A., Miles, D., Kidd, G., & Stanton, S. (2021). Developing youth justice policy and programme design in Australia. Australian Journal of Public Policy, 81(2), 367–382. DOI https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12524

Case, S., & Hazel, N. (2023). Child First: Developing a new youth justice system. London, UK: Palgrave MacMillan. DOI https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-19272-2

Clancey, G., Wang, S., & Lin, B. (2020). Youth justice in Australia: Themes from recent inquiries. Trends & Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice, 605, Canberra, Australia: Australian Institute of Criminology. DOI https://doi.org/10.52922/ti04725

Day, A. M. (2023). ‘It’s a hard balance to find’: The perspectives of youth justice practitioners in England on the place of ‘risk’ in an emerging ‘child-first’ world. Youth Justice, 23(1), 58–75. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/14732254221075205

Day, A., & Malvaso, C. G. (2024). ‘Back to Basics’: A practice approach to reforming youth justice. Child and Youth Services, 46(3), 536–560. DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935X.2024.2372790

Day, A., & Malvaso, C. (2025). Key components of high-quality child-centred casework in youth justice. HM Inspectorate of Probation, Academic Insights 2025/02. hmiprobation.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk https://hmiprobation.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/document/key-components-of-high-quality-child-centred-casework-in-youth-justice/

Day, A., Malvaso, C. G., Boyd, C., Hawkins, K., & Pilkington, R. (2023). The effectiveness of trauma-informed youth justice: A discussion and review. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1157695. DOI https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1157695 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37744608

Department of Human Services. (2022). Trauma Responsive System Framework. Adelaide, Australia: South Australian Government. dhs.sa.gov.au https://dhs.sa.gov.au/how-we-help/child-and-family-support-system-cfss/about-cfss/early-intervention-research-directorate/trauma-responsive-system-framework

de Ruiter, C., Burghart, M., De Silva, R., Griesbeck Garcia, S., Mian, U., Walshe, E., & Zouharova, V. (2022). A meta-analysis of childhood maltreatment in relation to psychopathic traits. PLoS ONE, 17(8), e0272704. DOI https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0272704

Fisher, M., Baum, F., MacDougall, C., Newman, L., & McDermott, D. A. (2015). Qualitative methodological framework to assess uptake of evidence on social determinants of health in health policy. Evidence and Policy, 11(4), 491–507. DOI https://doi.org/10.1332/174426414X14170264741073

Hamilton, H., Malvaso, C. G., Day, A., Delfabbro, P., & Hackett, L. (2024). Understanding trauma symptoms experienced by young men under youth justice supervision in an Australian jurisdiction. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 23(4), 333–348. DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/14999013.2024.2323939

Hill, L., Barnett, J. E., Ward, J., & Schmidt, A. T. (2023). Trauma-informed care for justice-involved youth: A narrative review and synthesis. Juvenile Family Court Journal, 74, 21–33. DOI https://doi.org/10.1111/jfcj.12236

HM Chief Inspector of Prisons. (2025). Building trust: The importance of positive relationships in young offender institutions. London, UK: HM Inspectorate of Prisons. hmiprisons.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk https://hmiprisons.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmipris_reports/building-trust-the-importance-of-positive-relationships-in-young-offender-institutions

Jones, L., Winder, B., & Day, A. (2024). Being humane in inhumane places: A collection of papers about trauma-informed forensic practice. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 23, 313–320. DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/14999013.2024.2408303

Malvaso, C., & Day, A. (2025). Towards an evidence-driven and trauma-informed approach to the delivery of juvenile justice services. Advancing Corrections Journal, 19, ACJ19-A001. icpa.org https://icpa.org/resource/advancing-corrections-journal-edition-19-excellence-in-juvenile-justice-policy-and-practice-article-1-acj19-a001.html

Malvaso, C. G., Day, A., & Boyd, C. M. (2024a). The outcomes of trauma-informed practice in youth justice: An umbrella review. Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma, 17, 939–955. DOI https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-024-00634-5 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39309340

Malvaso, C. G., Day, A., McLachlan, K., Sarre, R., Lynch, J., & Pilkington, R. (2024b). Welfare, justice, child development and human rights: A review of the objects of youth justice legislation in Australia. Current Issues in Criminal Justice, 36(4), 451–471. DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/10345329.2024.2313784

Malvaso, C., Santiago, P., Pilkington, R., Montgomerie, A., Delfabbro, P., Day, A., & Lynch, J. (2020). Youth justice supervision in South Australia. Adelaide, Australia: BetterStart Child Health and Development Research Group, The University of Adelaide. health.adelaide.edu.au https://health.adelaide.edu.au/betterstart/ua/media/136/yj-supervision-in-sa-report.pdf

National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN). (2015). Essential elements of a trauma-informed juvenile justice system. Rockville, MD, USA: NCTSN. nctsn.org https://www.nctsn.org/resources/essential-elements-trauma-informed-juvenile-justice-system

Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice. (4th edn). Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage Publications.

Phillips, C. L. (2019). A cross‐disciplinary study on formulating child health policy with a focus on the social determinants of health – an Australian perspective. PhD thesis. Adelaide, Australia: College of Medicine and Public Health Flinders University.

Purtle, J. (2020). Systematic review of evaluations of trauma-informed organizational interventions that include staff trainings. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 21(4), 725–740. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838018791304 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30079827

Rhodes, K., Rhodes, A., Bear, W., & Brendtroe, L. (2021). Moving the needle: Cultivating systemic change in juvenile services. Journal of Juvenile Justice Services, June, 89–100. irp.cdn-website.com https://irp.cdn-website.com/45a58767/files/uploaded/2021-Moving%20the%20Needle%20(Rhodes).pdf

Skuse, T., & Matthew, J. (2015). The trauma recovery model: Sequencing youth justice interventions for young people with complex needs. Prison Service Journal, 220, crimeandjustice.org.uk https://www.crimeandjustice.org.uk/sites/default/files/PSJ%20220,%20Trauma%20recovery.pdf

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration (SAMHSA). (2014). SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. Rockville, MD, USA: SAMHSA. library.samhsa.gov https://library.samhsa.gov/product/samhsas-concept-trauma-and-guidance-trauma-informed-approach/sma14-4884

Yoder, J., & Tunstall, A. (2022). Cascading effects of cumulative trauma: Callous traits among justice involved youth. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 20(4), 292–311. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/15412040221101922

Supplementary material is available on the live site https://childrenaustralia.org.au/journal/article/3062/#supplementary